Canada, celebrated for its multicultural identity and commitment to diversity, also stands on a foundation shaped by rich and intricate relationships among First Nations, Metis, Inuit, and a settler society. Canada’s National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, commemorated on September 30, is a landmark initiative established in 2021. It represents a critical step towards acknowledging and rectifying the painful history of settler colonization, systemic injustices, and intergenerational trauma experienced by Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation (NDTR) came to be as one way to recognize the tragedies surrounding the Indian Residential School system in Canada that operated between 1831 and 1996, which saw over 150,000 First Nations, Metis, and Inuit children forced to attend more than 130 schools across the country. It is a day to honour the children who died at the schools and the resilience of survivors and their families. It is also a day to confront and heal from many uncomfortable truths of the past. By officially acknowledging the historical trauma inflicted upon Indigenous individuals and communities, the NDTR is one mechanism to catalyze a national conversation about and make tangible steps to advance reconciliation, accountability, and social transformation, and create a more inclusive society.

The National Day of Truth and Reconciliation is an opportune moment to reflect upon views from the Asia Pacific, where 70 per cent of the global Indigenous population resides. The NDTR has its roots in Canada’s historical and present-day experiences, but similar narratives echo among Indigenous Peoples worldwide, including amongst the diverse peoples and cultures of Asia, where Indigenous Peoples have their own unique relationships with state governments and broader society. This Dispatch emphasizes the diversity of Indigenous Peoples and their perspectives on truth and reconciliation. The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada has engaged with Indigenous voices in Canada, Taiwan, Japan, Aotearoa New Zealand, and Australia, mirroring our 2021 Dispatch’s focal areas. APF Canada asked contributors to reflect upon three questions:

- What does truth and reconciliation mean for your community and in your country/region?

- What are the main challenges for advancing truth and reconciliation for your people and in your country/region? What could be done to elevate reconciliation efforts?

- How do you think Indigenous People in your country/region could work together with Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada to raise awareness about and advance truth and reconciliation?

It is our belief that the experiences of Indigenous communities in Canada and throughout the Asia Pacific shared by these leaders will help bridge cultural divides, illuminate historic injustices within a broader global context, and provide an opportunity for reflection that will contribute to reconciliation processes in Canada and the Asia Pacific.

– APF Canada's Northeast Asia team: Dr. Scott Harrison (Senior Program Manager), Sue Jeong (Junior Research Scholar), Momo Sakudo (Research Scholar), and Tae Yeon Eom (Research Scholar).

Limuy Asien, Atayal Indigenous filmmaker (Taiwan)

On the government website of Taiwan’s Indigenous Historical Justice and Transitional Justice Committee, one can find a repository of recordings of the Committee’s biannual meetings. Presided over by President Tsai Ing-wen, these meetings serve as a gathering site for Indigenous and settler representatives to report back on and work through pressing issues regarding Indigenous livelihoods and historical injustice, with a focus on issues such as land disputes involving the demarcation of Indigenous territories and the exploitation of land by state and private companies. Recently, the question of whether the ‘Pingpu, or ‘Plains Indigenous peoples,’ should be granted Indigenous legal status and how such recognition could potentially affect the amount of resources shared among Indigenous peoples have become thorny topics on the meeting agenda and among the members of Taiwan’s Council of Indigenous Peoples.

On the government website of Taiwan’s Indigenous Historical Justice and Transitional Justice Committee, one can find a repository of recordings of the Committee’s biannual meetings. Presided over by President Tsai Ing-wen, these meetings serve as a gathering site for Indigenous and settler representatives to report back on and work through pressing issues regarding Indigenous livelihoods and historical injustice, with a focus on issues such as land disputes involving the demarcation of Indigenous territories and the exploitation of land by state and private companies. Recently, the question of whether the ‘Pingpu, or ‘Plains Indigenous peoples,’ should be granted Indigenous legal status and how such recognition could potentially affect the amount of resources shared among Indigenous peoples have become thorny topics on the meeting agenda and among the members of Taiwan’s Council of Indigenous Peoples.

Some of these issues continue to affect people in the Naro Indigenous community where I grew up. Reserved Indigenous lands are being sold to outside investors with the help of legal loopholes. On Google Maps, it seems as if my community is being encroached upon by ever-expanding campgrounds catering to settler tourists. The influx of tourists to these campgrounds has significantly affected the community members’ access to water resources.

What could transitional justice mean for my community? Here, I’d like to mention some changes happening at the elementary school I attended. With the sustained efforts of several Indigenous teachers and elders, my elementary school is now transitioning to become an Indigenous experimental school. Children from my community now have Atayal language lessons on a weekly basis, while two decades ago, when I was attending the school, the Indigenous language instructor would only show up every other week as there was a shortage of these instructors. These days, I often bump into children who proclaim excitedly that they are training to become a hunter or children who are getting ready to compete in the National Spelling Bee for the Atayal language.

Despite the government’s attempt to right structural wrongs left by successive colonial regimes and the progress made after President Tsai’s apology in 2016 to advance Indigenous cultural and educational rights, Indigenous communities in Taiwan are still grappling with the consequences of land seizures, displacement, and social and economic disadvantage that continue to threaten their existence. The demarcation of Indigenous traditional territories, which only takes into account public lands rather than privately owned ones, facilitates the exploitation of Indigenous territories and impedes the development of Indigenous cultures. The government reparations in the form of monetary compensation also cannot do away with the fact that cement mines, transmission towers, and nuclear storage sites, amongst other kinds of colonial wreckage, are still very much there on Indigenous lands.

In response to these top-down approaches to reconciliation, protests initiated by Indigenous collectives have taken place. The Indigenous Justice Classroom (原轉⼩教室), for example, initiated the Ketagalan Boulevard Protest in 2017 that saw camps set up in front of the Presidential Office Building on Ketagalan Boulevard to protest unjust land demarcating regulations. In addition, artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers from various Indigenous communities have helped open up political space through their bottom-up projects that target Indigenous, settler, and potentially global audiences. Their works make visible complex and oftentimes unknown histories of Indigenous struggle, survival, and resurgence and encourage us to think beyond (failed) state-directed forms of transitional justice. Similar to the promotion of Indigenous cultures and languages by people in my community, the framework of transitional justice has been challenged and supplemented by the efforts of those who are not satisfied by legal and state action alone.

Taiwan is not a member of the United Nations and may be unable to participate in the UN’s Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues as an official political entity. Despite this exclusion, there have long been other forms of cultural and artistic exchanges between Taiwan and the wider Indigenous world.

At least one member of the Committee I mentioned earlier, for example, has travelled to Canada to raise awareness about Indigenous issues in Taiwan. On the film front, there have been screenings of important Indigenous documentaries from Taiwan at several film festivals in Canada. This coming October, Atayal Indigenous filmmaker Laha Mebow, the first woman from Taiwan to win Best Director at Taiwan’s Golden Horse Film Festival, will visit filmmaker Katsitsionni Fox on the Mohawk Territory of Akwesasne before heading to imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival in Toronto, the largest gathering of Indigenous filmmakers from around the world. Though not always linear or triumphant, the sharing of stories and histories may provide possible grounds for solidarity and for new ideas about truth and reconciliation to take root.

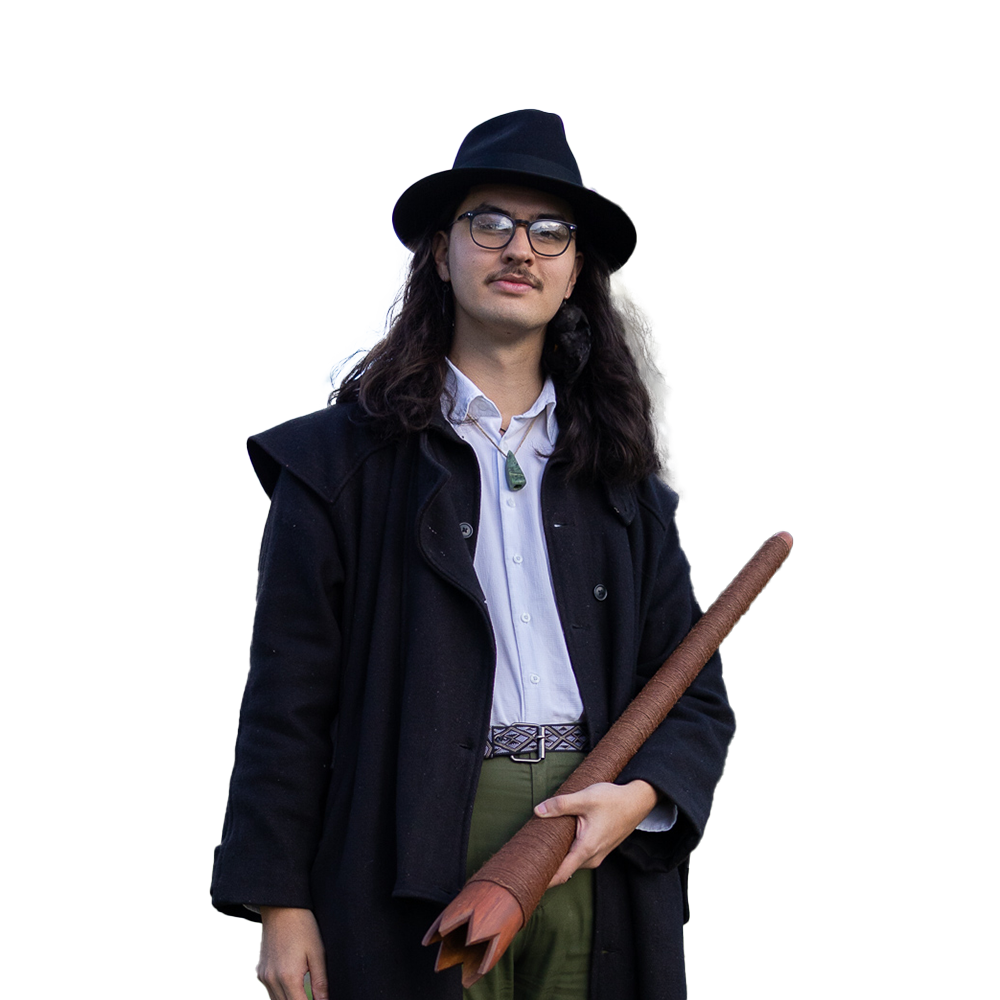

Mikaere Berryman-Kamp, Māori Educator and Advocate (New Zealand)

The process of truth and reconciliation is ongoing, and its manifestation varies across communities and groups. In New Zealand, a common narrative I heard growing up was that we had no history. As you get older, you begin to understand that Māori history in New Zealand is often intentionally left aside in an attempt to mask the hurt and trauma caused post-settlement. This is why the truth is imperative, so individuals can understand the factors that have contributed to many of the problems we, as Indigenous Peoples, face. The truth must be discussed freely and frankly, especially with our younger generations, so they can understand the path their tūpuna (ancestors) have walked and the journey that lies ahead. Through unmasking the facts, context is learned that helps to affirm the path forward. This process is not a quick fix, nor is it a tick-box exercise. It is a slow and deliberate series of actions that uphold the promises made to Indigenous Peoples.

The process of truth and reconciliation is ongoing, and its manifestation varies across communities and groups. In New Zealand, a common narrative I heard growing up was that we had no history. As you get older, you begin to understand that Māori history in New Zealand is often intentionally left aside in an attempt to mask the hurt and trauma caused post-settlement. This is why the truth is imperative, so individuals can understand the factors that have contributed to many of the problems we, as Indigenous Peoples, face. The truth must be discussed freely and frankly, especially with our younger generations, so they can understand the path their tūpuna (ancestors) have walked and the journey that lies ahead. Through unmasking the facts, context is learned that helps to affirm the path forward. This process is not a quick fix, nor is it a tick-box exercise. It is a slow and deliberate series of actions that uphold the promises made to Indigenous Peoples.

Identity – of place, person, and more – can be challenged as we progress the journey of truth and reconciliation. While reclaiming traditional place names plays a pivotal role in asserting indigeneity, its significance often goes unrecognized. At home, there are those who refuse to acknowledge these ‘new names,’ as they have lived their whole life with a different idea of where they call home. Individuals feel they have deep roots in New Zealand due to having family that has inhabited the land for over a hundred years, but turn a blind eye to those that have lived in Aotearoa for close to a thousand. As Te Reo Māori (Māori language) gains more public recognition and backing, those who do not understand can feel like their identity is under attack, and the New Zealand they know and love is slipping away. The issue boils down to a lack of understanding of our [Indigenous] histories, and the fact that our names are more than just words. They are markers of history, ecological indicators, signposts, declarations of love, and more. A name may be just a name to some, but to us, it is the public recognition and validation of our world, each and every day.

Education via the mainstream is a strong solution to address tensions with identity. Individuals like Te Rauhiringa Brown, who sparked debate by presenting the weather with Māori place names, should be recognized for their persistence and resilience to promote our reality to the wider population. Changing a word at a time may seem insignificant, but the continual use of our vernacular is a gentle reminder that we are still here, and our world is alive and well. This also applies to the wearing of traditional adornments in mainstream spaces, be they jewellery, tattoos, or clothing.

As Indigenous communities, we exist as different strands intricately woven together by shared experiences. Each strand is different but can relate to another through histories, pre- and post-settlement. In the Asia Pacific, advocacy is hugely important as we see the climate crisis worsening, and its effects on those throughout the region. For years these communities have been exploited and are now largely ignored as the seas rise and disasters strike every year. As mentioned previously, truth and reconciliation should not be rushed, but the Asia Pacific region is having to face the reality of forced migration as [Indigenous] traditional lands disappear.

The role of Māori and Indigenous Peoples in Kanâta (Canada) should be one of publicity and outspoken support when it comes to climate disasters and recognition of Indigenous Peoples. Those in the Asia Pacific could further be supported through treaty processes to seek ratification and an angle to pressure various governments in the regions. Our people have walked that journey and learned a lot along the way, which could be of immense help. The rise of online tools also allows for more opportunities to support than ever before, especially with resource constraints on particular islands. Kanohi ki te kanohi (face to face) is where we shine as Indigenous Peoples, but virtual exchanges and workshops can inspire creative ways forward.

Dr. Kiri Dell, University of Auckland Senior Lecturer, Management and International Business (New Zealand)

Truth and reconciliation are not common terms used in the national decolonizing discourse of Aotearoa (New Zealand). Rather, the prevailing terms here encompass settlements and grievances. Originating from the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand’s founding document and an agreement made by representatives of the British Crown and about 540 Māori Rangatira (chiefs), meant to signal an arrangement for mutual partnership. However, the British subsequently disagreed these original intentions, opting to subjugate the Māori, enforce their social and legal systems, and violently strip [Māori] resources such as land and language. In these modern times, the Treaty of Waitangi is considered New Zealand’s founding document that expresses the intention of the two parties’ partnership that is to be respected and honoured. Hence, the language born out of rectifying the wrongs of the Treaty becomes our country’s version of truth and reconciliation.

Truth and reconciliation are not common terms used in the national decolonizing discourse of Aotearoa (New Zealand). Rather, the prevailing terms here encompass settlements and grievances. Originating from the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand’s founding document and an agreement made by representatives of the British Crown and about 540 Māori Rangatira (chiefs), meant to signal an arrangement for mutual partnership. However, the British subsequently disagreed these original intentions, opting to subjugate the Māori, enforce their social and legal systems, and violently strip [Māori] resources such as land and language. In these modern times, the Treaty of Waitangi is considered New Zealand’s founding document that expresses the intention of the two parties’ partnership that is to be respected and honoured. Hence, the language born out of rectifying the wrongs of the Treaty becomes our country’s version of truth and reconciliation.

Despite the persistence of overly racist behaviours and outdated viewpoints in this country, I remain optimistic, believing that Aotearoa predominantly holds goodwill and a genuine intent to rectify the past misdeeds. Where we do get into challenges is truly understanding what partnership means. Many people in the country are struggling with the idea of Māori being a partner to the Crown. Resistant catchphrases like “one law for all” and “we are all one people” (which are actually a reinvented form of assimilation ideologies) are spouted to try and portray Māori/Crown partnerships as a form of national separatism. But it is the reverse. Although many gains have been made in Aotearoa, many Māori communities are still in disarray and fragmented. The main challenge for Pakeha (a Māori-language term for New Zealanders primarily of European descent) is to altruistically permit the replacement of resources to Māori communities. Then, step away to give space for Māori to empower, engage, and enjoy the mere fact of being Māori – uninterrupted. Strong, collaborative, positive, and merging partnerships with settlers then become a natural consequence of that process.

At the risk of sounding cliché, the adage “the sum of us is bigger than its parts” holds weight, emphasizing the importance of unity. But importantly, there is a step before that, which is to provide state support to Indigenous communities to experience the process and states of just being Indigenous, without political agitation or social and cultural deprivation. Indigenous Peoples need to have the repeated experience of feeling the joy of just being themselves.

Trau Pakaruku Sawma, Pinuyumayan Cultural and Political Leader (Taiwan)

(Translated from Mandarin Chinese by Dr. Scott E. Simon, Professor, University of Ottawa)

(Translated from Mandarin Chinese by Dr. Scott E. Simon, Professor, University of Ottawa)

The challenge of truth and reconciliation in Taiwan lies in the reluctance to confront the truth and the uncertainty surrounding the definition of reconciliation. During martial law in Taiwan (1949 to 1987), we were not allowed to talk about these things. Now the young generation of people born since the 1980s do not yet know the answers to these questions.

In 1999, the Indigenous Peoples of Taiwan signed a new partnership agreement with presidential candidate Chen Shui-bian. In 2005, the Indigenous Peoples Basic Law was passed, but many of its provisions have not yet been implemented. When Ma Ying-jeou was president, he wanted to propose a self-government act [for Taiwan’s Indigenous Peoples], but it was not passed. Now President Tsai Ing-wen made her apology and created a commission on transitional justice. They have written many reports, but they did not reach out to ordinary Indigenous People.

We are now establishing our own national committee. We need to have meetings and decide what we want. Between 2000 and 2023, all the successful Indigenous intellectuals have taken jobs in the current system. We all benefit from social welfare, but we need our land back. Most of the demands of the social movement have been obtained, but we have not gained our land back. Mainstream society should be able to accept our demands for self-government, but there are differences of opinion. We will begin our work in 2024 and need to express our needs.

Dr. Kanako Uzawa, Founder, AinuToday & Assistant Professor, Hokkaido University (Japan)

From my personal view, there are three steps for truth and reconciliation in Japan. The first would be an official apology from the Japanese government and universities where stolen human remains have been held. The second entails formulating policies and strategies in dialogue with Japan’s Indigenous Peoples. The third step would be implementing these policies and measures. What I mean here in terms of truth and reconciliation includes addressing the historical wrongdoings of the past that have been done to the Indigenous People and to the land and natural resources, such as the theft of human remains, disposition of the land, sexual violence, military invasion, seizing of natural resources, human rights violations, unethical research conduct, and how the law was formulated to the benefit of Japanese and at the expense of Ainu sovereignty.

From my area of expertise on Indigenous research methodologies, I wish the government and the universities would provide the Ainu more financial support, opportunities, and space to those who wish to lead research projects in their own communities. And I think one of the strategies that is important is to have Indigenous scholars serve as role models to young people who might then become interested in becoming Indigenous researchers themselves. It is especially important for Indigenous researchers to have full authority over their own research and the research being conducted in their communities.

The general impression that I receive in the Ainu communities is that awareness of Indigenous rights is particularly low, and much focus is centred around cultural preservation and development. For them, truth and reconciliation might involve recognition of their own work and financial support for the continuation of their cultural preservation. They might also want to see initiatives that provide employment for young people in their communities.

It is difficult because the Ainu do not have any solid ground to start a discussion on truth and reconciliation. The awareness or understanding of the concept of truth and reconciliation is low, which means we must start by educating people about the concept by the initiative of Indigenous Peoples themselves, rather than outside ‘experts.’ For reconciliation to gain prominence, it is imperative to foster an environment for open discourse, which needs to be initiated and led by Indigenous Peoples but must include both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in the discussion.

It would be helpful to start a dialogue about shared experiences. However, forging a tangible strategy for progress remains crucial, because sometimes those meetings begin and end with learning about other peoples’ situations, without going further due to differences in legal frameworks or other challenges in implementation. So, we need to learn about successful cases of implementation and then distill a few key points where specifics could be modified to apply to the unique situation of Japan. Indigenous leaders from Canada could help to raise awareness of the concept of truth and reconciliation, what it means, and how it would look in practice.

Raylene Whitford, INDIGI-X Program Director (Canada)

Truth is central to advancing any type of reconciliation and must come first. Canada, as a nation, is still in the nascent stage of comprehending the severe harms and injustices it inflicted – and continues to inflict – upon its Indigenous Peoples.

Truth is central to advancing any type of reconciliation and must come first. Canada, as a nation, is still in the nascent stage of comprehending the severe harms and injustices it inflicted – and continues to inflict – upon its Indigenous Peoples.

Reconciliation, to me, means:

- Addressing injustices and facilitating equity and equality: legally, socially, and economically

- Closing the gap in areas such as health, education, employment, and standards of living

- Strengthening education, understanding, and ultimately, the partnerships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people

- Creating respectful, mutually beneficial, and long-lasting relationships

Recently, there has been an increased focus on the economic aspect of reconciliation. And rightly so. However, I do think the relationships aspect of reconciliation holds significance and warrants further progression. While no monetary compensation can truly rectify the endured suffering, fostering genuine relationships can pave the way for healing.

I think the Canadian public is broadly supportive and understands the importance of this movement. Now, it is time for government and industry to follow suit. The federal government’s action plan to implement UNDRIP [the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples] is a good start, but we must increase the pace to advance this. Industry and corporations are also making some efforts, but without their full endorsement of reconciliation – both relationally and economically – the genuine impact will remain unrealized.

The Asia Pacific region is home to the largest – and possibly most diverse – population of Indigenous Peoples in the world. There is tremendous power in creating a global community of support and one that will advocate for collective action, such as creating a space to learn and share best practices with each other.

A wonderful example of this is INDIGI-X – a network of Indigenous Changemakers from Canada, Aotearoa New Zealand, and Australia. By simply facilitating a platform for Indigenous leaders from diverse backgrounds, sectors, and geographies to gather and share knowledge, incredible solutions are found and relationships formed – many of which have now evolved into commercial partnerships, policy advisory, and international trade. Underpinning the program, though, is a shared understanding and support for others who have experienced – and continue to experience – colonial violence, and an unwavering commitment to work together against these inequalities.

Someone recently shared with me, “Alone we are a tax number. Together we are collective strength.” This is a good example of what global advocacy for reconciliation could look like.