By the time Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe wrapped up his three-day visit to Beijing on October 27, companies from both countries had signed agreements to co-operate on more than 50 infrastructure projects, including building a smart city in Thailand. The occasion marked the first official visit by a Japanese leader to China since 2011, with Abe characterizing it as a “historic turning point . . . switching from competition to collaboration” in a bilateral relationship that seemed to have reached its lowest point following a series of historical and territorial conflicts in recent years.

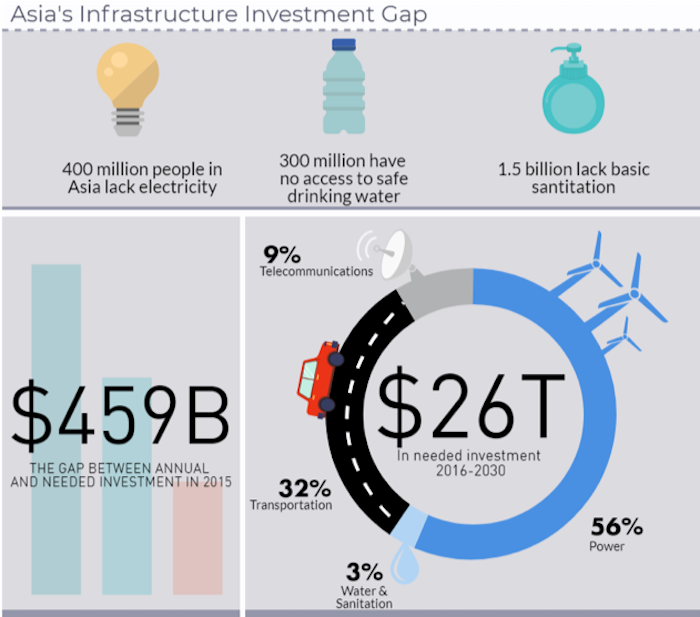

This seeming rapprochement, however, is undercut by heightened competition between the two regional powers, notably in the realm of infrastructure development, to acquire and maintain influence within and beyond the continental neighbourhood. Since China launched its much-vaunted Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, Japan as well as ASEAN, India, Iran, Russia, South Korea, the European Union, the United States, and Turkey have all announced new infrastructure plans of their own, indicating that the race is on to reap the social, political, and security benefits of filling Asia’s capacious multi-trillion dollar infrastructure investment gap.

The Washington, D.C.-based Center for Strategic & International Security’s Reconnecting Asia project describes these efforts as competing visions, reflecting an evolving understanding among nations that it matters who builds in Asia. To be left behind is to risk not only losing political favour in neighbouring countries, but potentially the ability to protect one’s regional security interests. Simply put, who controls which port, road or railway and where, who is in debt to whom, and which country is providing the best public infrastructure will have a lasting effect on the balance of power both in Asia and globally.

Connecting Asia and Beyond

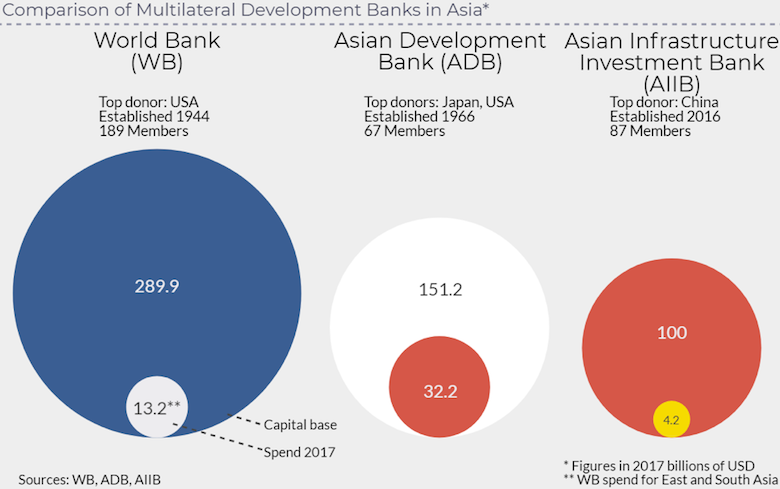

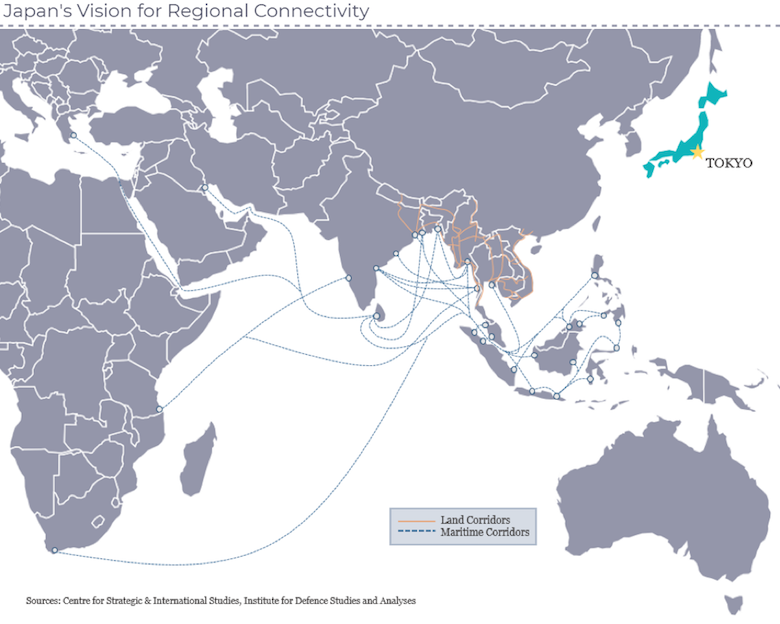

Among regional powers seeking to compete with China’s BRI, Japan has pursued the most wide-ranging and comprehensive set of plans, spanning from the island nation westward through Asia, reaching as far as the African continent. Japan has long been the dominant player in regional infrastructure development – the Japanese-backed Asian Development Bank has been dolling out funds since 1966 – but Tokyo has found a new urgency in the five years since the BRI was launched.

Japan’s actions can be understood as a form of ‘infrastructure diplomacy,’ whereby countries aim to extend their influence through not only infrastructure financing, but also the planning, construction, and operation of projects. In this way, the country is able to secure bilateral agreements and foster cross-border co-operation in the private sector. Four of Japan’s recent infrastructure diplomacy plans are highlighted below. In the context of the rise of China, these initiatives should be understood as efforts by Japan to assert its influence and counterbalance China’s increasing assertiveness on the international stage.

The Partnership of Quality Infrastructure

Announced on May 21, 2015, Japan’s Partnership of Quality Infrastructure (PQI) came with a US$110-billion funding package, which experts were quick to note was a sly US$10 billion more than the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank’s (AIIB) initial capitalization of US$100 billion. Japan subsequently increased the PQI’s funding to US$200 billion in 2017 to include projects in Africa and the South Pacific as well as Asia. According to the Japanese government, the quality, rather than the quantity, of investments sets the PQI apart, as does its commitment to environmental and financial sustainability. This emphasis seems to be a direct dig at China’s BRI, which has been criticized for creating debt traps, producing infrastructure with poor build quality, and not benefitting local people. For its part, Japan cites the Mombasa Port in Kenya, the Mumbai-Ahmedabad High Speed Railway in India, and the Digital Grid Project in Tanzania as three examples of PQI-quality infrastructure projects under the country’s umbrella.

Tokyo Strategy 2018 for Mekong-Japan Co-operation

Under the banner of the Tokyo Strategy 2018, Japan pledged to assist Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar in more than 150 projects through 2021. The Strategy focusses on quality-building in three main areas: effective connectivity, building people-centred societies, and environment and disaster management. Mekong countries have become eager for alternative financing amid mounting concerns about the implications of accepting too much Chinese capital. Thailand rejected proposals and refused to grant land rights for Chinese infrastructure investments in 2016, citing Laos’ precarious situation where its US$6.7 -billion loan amounts to half the country’s GDP. Myanmar, despite its appetite for outside investment, scaled back its US$7.3-billion BRI-funded Kyauk Pyu Deepwater Port to just US$1.3 billion “over concerns it is too expensive and could ultimately fall under Beijing’s control.”

Importantly, Japan’s contribution was reciprocated by an affirmation by Mekong leaders of their support for reinforcing a rules-based order to maintain freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, in line with Japan’s ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy’ (FOIP). This is an important piece in the geopolitical puzzle as the Mekong region is strategically significant owing to its proximity to the increasingly contested South China Sea and position between two major continental powers, India and China.

Africa-Asia Growth Corridor (AAGC)

The Africa-Asia Growth Corridor (AAGC) is a collaborative effort between Japan, India, and several African countries announced in 2016 to promote better connectivity between the two regions and support economic development in Africa. Here the competition with China, which has made major inroads on the continent, is impossible to miss. Resting on the key features familiar under Japan’s other infrastructure initiatives, the AAGC’s commitment to quality, transparency, and sustainability once again place in stark relief the ‘Japan brand’ against that of China, with the latter’s infrastructure boom in Africa coming under increased scrutiny, again, for its potential threat to nations’ financial and political independence.

What Does It All Mean?

Through these initiatives, three key aspects of Japan’s foreign policy can be interpreted. First, Japan’s increasing assertion of its reputation as a leader in quality infrastructure as a means of competing with China’s overwhelming economic heft. Japanese Prime Minister Abe highlighted this reputation during the PQI’s launch at the 21st International Conference on the Future of Asia, saying, “that is the Japanese way of operating” and emphasized his government’s position that “in order to make innovations extend to every corner of Asia, we no longer want a ‘cheap, but shoddy’ approach.” These statements place in stark relief global perceptions of Japan’s and China’s respective brands. This point of differentiation is important given the reality that Japan is unable to compete with China on a dollar-to-dollar basis, even if it partners with other powers such as the U.S. and India.

Second, Japan's reactiveness to BRI developments demonstrates the country's concern with being geoeconomically edged out by its ascendant competitor. For example, the FOIP was first adopted in 2007 as “the dynamic coupling as seas of freedom and prosperity,” but would lay dormant for 10 years before being revived in November 2017 by Japan, Australia, India, and the U.S. on the sidelines of the East Asia Summit in the Philippines. The launch of the PQI occurred conspicuously on the heels of the establishment of China’s AIIB only five months prior, and one month before the founding member nations were set to sign the AIIB’s Articles of Agreement in China’s Great Hall.

The Mekong-Japan summit, too, has evolved in the wake of the BRI. Though the summit has convened annually since 2009 to pursue sustainable development and narrow the development gap in the region, this year's iteration was notable as the two sides agreed to elevate their ongoing economic co-operation to a strategic partnership, with Mekong countries’ affirming their support for the FOIP.

Third, Japan sees infrastructure development as intimately linked to strategic security. Since 2017, Tokyo has explicitly linked the FOIP concept with its infrastructure development schemes. In addition to the previously mentioned Tokyo Strategy, a presentation given by the Special Advisor to the Prime Minister of Japan on Japan’s initiatives for promoting quality infrastructure investment featured prominently the FOIP, ahead of any actual infrastructure projects. Under the framework of the FOIP, the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia moved to resurrect the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue , and included among its seven themes the enhancement of connectivity as a critical component of regional peace and prosperity.

For its part, Canada has long been involved in Japan’s infrastructure endeavours, having joined the ADB as a founding member in 1966 and contributing US$7.91 billion to date. A change in government and renewed interest in rekindling relations with China has spurred Canada to diversify its strategy, reversing its previous stance on the AIIB and belatedly joining in mid-2017 with a pledge of US$199 million over five years. Membership in both banks provides Canada a seat at the table in two important multilateral development institutions in the region, but with a poor record of pitching to the WB and ADB, it remains to be seen if the Canadian corporate sector will be motivated to bid on contracts for transportation, power, and sanitation projects in the region.

Conclusion

Japan’s leadership in Asia seemed to wane amid China’s monumental economic growth and the fanfare surrounding the BRI, but recent developments, particularly in infrastructure development, show that Tokyo still has the ability to use its economic might and political clout to counter Chinese influence. The Chinese capital infusion that was so welcome in many places where basic infrastructure is sorely needed has lost much of its attractiveness as countries become aware that there are indeed strings attached, most notoriously in debt-for-equity arrangements such as the case with Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port. Partners have been quick to emerge, too, as the rising tide of Chinese influence has stoked insecurities in countries like India and Australia and changing global power dynamics have spurred countries such as Canada to diversify their investment options. Ultimately no one country will be able to fill Asia’s infrastructure gap, but who builds what and where will determine the balance of power on the world’s fastest growing continent, and beyond.