What happens in Ukraine matters to Canada. Canada is a firm supporter of a rules-based international order and has the world’s third-largest Ukrainian population outside of Ukraine and Russia, with about 1.4 million people of Ukrainian ancestry. The unfolding crisis in Ukraine also matters to Asia, although in somewhat different ways, creating dilemmas for Asian leaders and providing a difficult reminder of how interconnected our world has become.

Russia’s connections to Asian economies vary. For some, Russia is an important source of energy, food and fertilizer, general trade, and military equipment. For others, relationships with Russia have strategic value vis-a-vis the U.S./West, and sometimes in terms of balancing relationships between the U.S. and China. These complexities help explain why some Asian governments have been reluctant to openly condemn Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine or take action to punish Russia economically.

At the same time, the invasion is a clear violation of international law. That Russia has interfered in another nation’s sovereignty and territorial integrity by force is disturbing for many in Asia, countries and societies that have their own painful experiences with colonialism, war, territorial and maritime disputes, and issues around ethnicity and culture. This Asia Watch Special Edition outlines some of these dilemmas and what we will be tracking as this crisis evolves.

China’s Uncomfortable Position on Russia’s War on Ukraine

China has been walking a tightrope since the beginning of the crisis in Ukraine, balancing support for Russia’s actions without contradicting its long-held principles of inviolable sovereignty and territorial integrity. Yes, China has criticized NATO and condemned Western sanctions on Russia. But while it has recognized Russia’s security concerns, China has refrained from backing Russia’s “special military actions” in Ukraine. Instead, Beijing has called for both parties to “resolve the issue through negotiation.” China abstained from voting on a UN Security Council resolution last Friday criticizing Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine rather than vetoing it, as Russia did. Many Western countries saw that move as a limit of China’s support for Russia.

There have been few reports of Chinese citizens speaking out against Russia’s war on Ukraine, and those that have were reportedly quickly detained. On social media, “inappropriate” media posts criticizing Russia are being deleted, leaving the Chinese online media seemingly largely pro-Putin. Some netizens wonder about the fate of the 6,000 registered Chinese nationals stranded in Ukraine. The Chinese Embassy in Kyiv cancelled evacuations via charter flights on the weekend due to security concerns, but on Monday began efforts to evacuate Chinese citizens via rail. Notably, the Embassy did not start any evacuation efforts until after Russia launched its military invasion. This has led some to wonder about China’s lack of preparedness and whether Moscow has been forthright with Beijing about its intentions.

Some question whether China will shift its position on Russia’s war, especially if the situation worsens. After all, China will not want to be seen supporting atrocities committed against civilians. And for all the talk about a Beijing-Moscow axis, it is worth remembering that, despite some shared geopolitical interests with Russia, the West is overall far more important economically for China than Russia. Indeed, China has reportedly not assisted Russia in evading economic sanctions. One reason may be that Beijing is being careful to avoid secondary sanctions or suffer from the fallout from a war in which it has no direct interests. Perhaps the only current benefit of this crisis for China is a distracted West, although a newly empowered and unified Western alliance could ultimately be more challenging for China.

READ MORE

- Al Jazeera: As Russia’s isolation grows, China hints at limits of friendship

- Financial Times: China ready to ‘play a role’ in Ukraine ceasefire

- The Guardian: China ponders how Russia’s actions in Ukraine could reshape world order

Southeast Asia Opposes Conflict But Not Russia

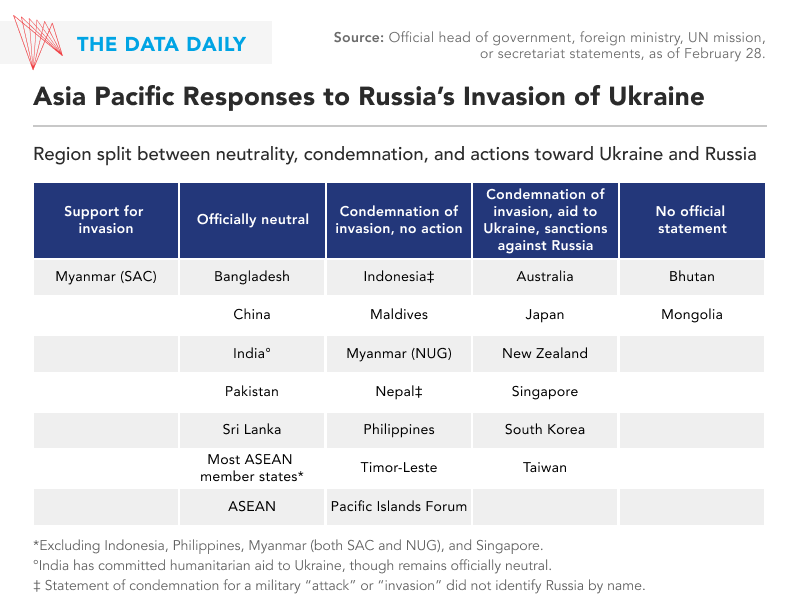

On Saturday, ASEAN’s 10 member states issued a terse statement, expressing “deep concern” over “armed hostilities” in Ukraine and calling for both sides to “pursue dialogue” seeking an end to violence in accordance with international law. The statement adheres firmly to ASEAN’s long-running stance of diplomatic caution and non-interference. Nonetheless, ASEAN members and others in the region have diverged in their responses to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Singapore most forcefully condemned the “unprovoked invasion of a sovereign state,” and Timor-Leste supported a draft UN resolution to end Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. While deploring the violence and calling for negotiation, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines focused on the safety of their citizens in Eastern Europe. Myanmar’s military junta, meanwhile, referred to Russia’s invasion as appropriate to defend its sovereignty.

ASEAN’s official moderate response and aversion to directly naming or criticizing Russia likely stems from economic and national security concerns. Russia’s trade with Southeast Asia is scant – accounting for less than one per cent of ASEAN’s total merchandise trade in 2020. But economies like Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam boast significant trade surpluses with Moscow and may seek to protect such trade advantages to further pandemic economic recovery. Russia is also a key defence supplier for the region, with Vietnam and Myanmar its top customers. U.S. and other international sanctions threaten Russian arms sales to Southeast Asia, as buyers could face repercussions for dealing with Russia. Cutting off the Russian defence supply would also disrupt Southeast Asia’s access to needed parts to maintain current Moscow-made military equipment.

The Ukrainian crisis is a flashpoint of geopolitical tensions reminiscent of the Cold War. In this context, Southeast Asia walking the line between criticism and self-protection may be reasonable, especially considering how the Cold War ran catastrophically hot throughout much of Southeast Asia. Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine may also set a dangerous precedent for Southeast Asian states that depend on international law to protect their sovereignty and statehood, especially vis-à-vis the heavily disputed South China Sea.

READ MORE

- The Diplomat: ASEAN Foreign Ministers express ‘deep concern’ about Ukraine Crisis

- Nikkei Asia: ASEAN faces fallout from Russian invasion of Ukraine

- The Strait Times: ASEAN countries including Cambodia and Malaysia call for diplomacy to resolve Ukraine-Russia conflict

India, Pakistan Have Competing Priorities in Russia-Ukraine Crisis

New Delhi and Islamabad have struck similar chords in their official statements on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, urging de-escalation but avoiding assigning blame for the violence. The two governments are squeezed between potentially irreconcilable positions. Both have recently staked a lot on their relationship with Moscow, seeking energy security, military hardware, and diplomatic leverage against rivals (including each other). They also know that being too muted in their response to Russia’s actions could damage their standing with the U.S. and other Western countries, with whom they also need strong relations.

New Delhi reinforced its long-standing relationship with Russia in December when President Vladimir Putin visited India. The meeting resulted in India acquiring the Russian-made S-400 missile defence system, a key asset in deterring attacks from Pakistan and China. In fact, half of India’s arms imports come from Russia. But there are tensions at the heart of this relationship: Russia’s close relationship with China and India’s membership in the Quad, a U.S.-aligned grouping Russia strongly opposes. India’s immediate concern vis-à-vis Ukraine, however, is not resolving these contradictions, but evacuating the thousands of Indian students stranded in Ukraine, many having reported harassment and discrimination at border checkpoints. The Indian foreign ministry said today that one student was killed in an airstrike.

Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan, who coincidentally met with President Putin in Moscow on Thursday as the Ukraine invasion was unfolding, is pursuing two goals with Russia. One is Moscow’s assistance in stabilizing Afghanistan. Another is the C$3.17-billion Russian natural gas pipeline that would run from Karachi to Pakistan’s Punjab region. Interestingly, the pipeline would not deliver Russian gas to energy-hungry Pakistan but would, in theory, draw Qatari gas exports away from Europe to nearby Pakistan, thereby making Europe more dependent on Russian-supplied gas. The status of both goals now seems uncertain. On Monday, Khan announced he would temporarily slash the cost of fuel and electricity to offset the spike in energy prices that is expected to result from the Russia-Ukraine crisis. His government had reduced fuel subsidies as part of the reforms required for an IMF bailout package, which Pakistan requested to help stabilize its economy. Such local-level impacts show the crisis is already being felt close to home.

READ MORE

- Al Jazeera: India, Pakistan take a similar diplomatic path on Russia-Ukraine

- The Diplomat: Ukraine invasion prompts tepid response from South Asia

- New York Times: Pakistan will cut energy prices to offset rising costs after invasion

Japan, South Korea Confront Russia; North Korea Eyes Situation Warily

Japan announced sanctions on Russia’s central bank yesterday, in concert with growing international efforts to isolate Russia after it invaded Ukraine. The Japanese government also announced sanctions against Belarusian officials and more than C$254 million in loans and aid to Ukraine. Japanese companies have voiced concerns about the possible impacts of the Ukraine crisis and international sanctions against Russia on Japan’s auto industry. Extensive Japan-Russia financial ties in Arctic development projects further add to concerns around fallout from sanctions. These interdependent relationships help explain why Japan was one of the only G7 countries initially hesitant to agree to block Russian banks from SWIFT, the international payments system, a position it reversed on Sunday.

A decades-old territorial issue between Russia and Japan over the ‘Northern Territories,’ a group of islands northeast of Hokkaido, could rise to the forefront again amidst the ongoing crisis. This issue has been a stumbling block in many aspects of their bilateral relations. And in an escalation of aggressive rhetoric between the two countries yesterday, former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo suggested that Japan consider hosting U.S. nuclear weapons similarly to NATO member countries. Such an arrangement would mean abandoning Japan's longstanding pacifist policy, and current PM Kishida Fumio called the proposal “unacceptable” given the country’s stance against nuclear weapons. Meanwhile, in response to Russia’s escalation of its nuclear threat, atomic bomb survivors marched against “another Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” At the same time, protesters in Fukushima expressed support for Ukraine, acknowledging the country’s support in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster.

South Korea’s government condemned Russia’s invasion yesterday, banning exports of weapons materials to Russia and pledging C$12.7 million in aid to Ukraine. It will join Western nations in blocking certain Russian banks from SWIFT. But it also intends to ask Washington to grant some exceptions to U.S. export sanctions on Russia, citing concerns for South Korea’s tech industry, which is deeply linked with both Russia and Ukraine. Meanwhile, the two major presidential candidates sparred over the implications of the crisis for South Korea in a debate yesterday, with both making controversial remarks. North Korea, meanwhile, blamed the U.S. and NATO for provoking the conflict in Ukraine while launching its first ballistic missile test in a month. The crisis will likely further the North Korean leadership’s fear of disarmament and denuclearization, and complicate efforts to restore trade between the country and its Russian and Chinese neighbours.

READ MORE

- The Korea Herald: Security emerges as key issue in presidential election as Ukraine crisis unfolds

- The Mainichi: Japan to let Ukrainian refugee applicants stay in country

- The Washington Post: In Japan and across Asia, an outpouring of support for Ukraine

This special edition of Asia Watch was brought to you by APF Canada research analysts Natasha Fox, Scott Harrison, Quinton Huang, Charles Labrecque, Daniela Rodriguez, and Erin Williams.