Overview

From January 29 to February 2, Canada’s Foreign Interference Commission held preliminary hearings as part of the Public Inquiry into Foreign Interference in Federal Electoral Processes and Democratic Institutions. The Commission was established by the Government of Canada on September 7, 2023, to “examine and assess” two things. The first is “interference by China, Russia, and other foreign states or non-state actors” in Canada’s 2019 and 2021 federal elections. The second is “the flow of information to senior decision-makers, including elected officials” and others, during and in the weeks following those two elections, and what actions these decision-makers took in response. On January 24, the Commission added India to the scope of its inquiry; however, the exact nature of the allegations vis-à-vis India remains unclear.

The purpose of this first set of hearings, which focused on the confidentiality around national security issues, was to assist the Commission in striking a balance between two imperatives: making as much of the information as public as possible, while also protecting the confidentiality of the sources and methods, given that much of this information comes from national security documents and sources that are classified as top secret.

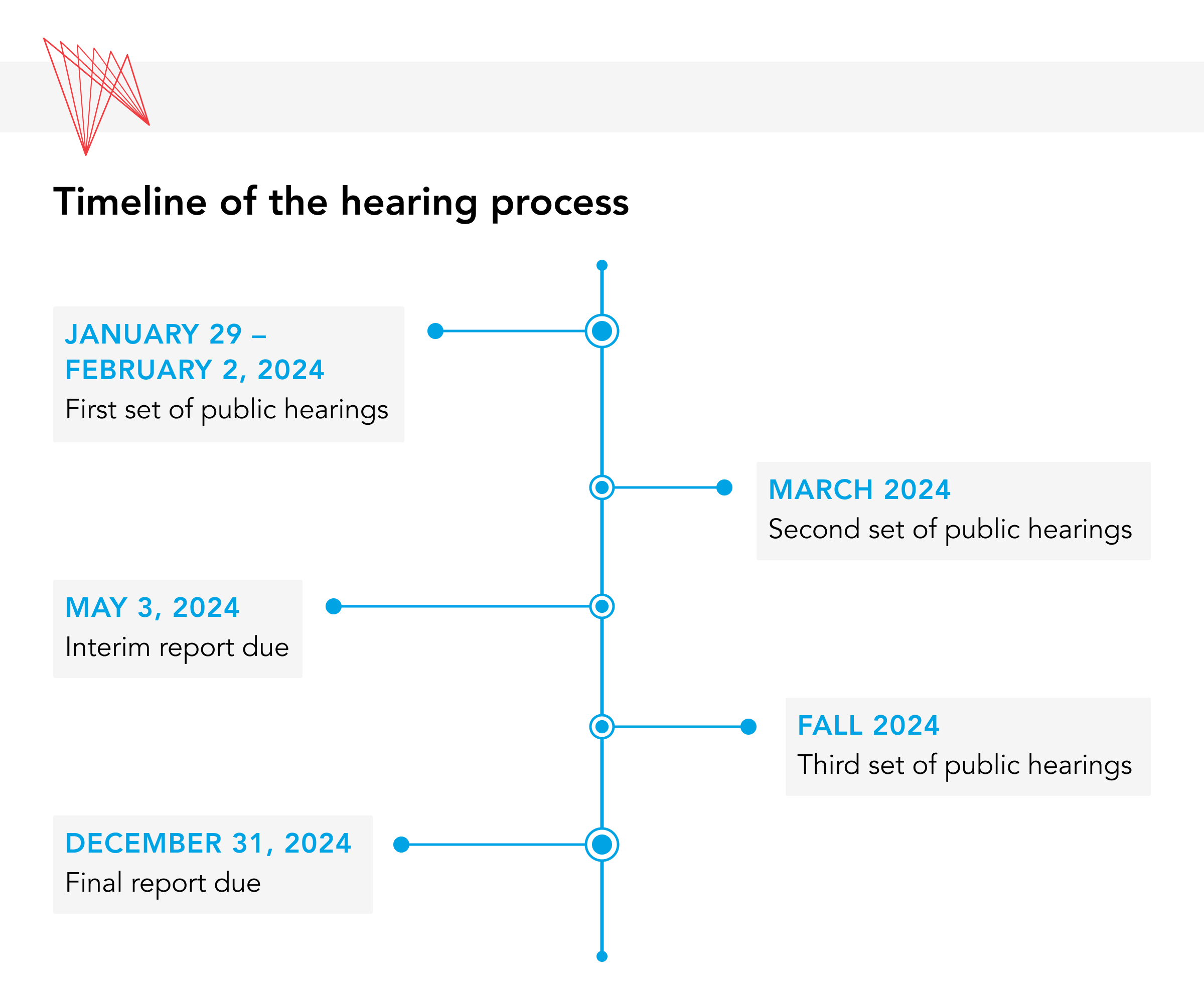

The public hearings will resume in March when the Commission will present and examine the evidence of foreign interference and its possible impact on the two elections in question. It will issue an interim report on May 3. A second ‘policy’ phase of work will take place in the fall to assess the federal government’s capacity to “detect, deter and counter” incidents of foreign interference. The Commission will submit its final report, with recommendations, by the end of 2024.

The facts established through the public inquiry and the steps Canada takes in response could have profound implications for our national security and the integrity of our democratic institutions. This Explainer is intended to help inform APF Canada’s stakeholders about key facets of this issue, including how foreign interference is defined, what events and revelations preceded and precipitated the public inquiry, and what to keep an eye on as the proceedings unfold.

APF Canada will publish a more detailed Policy Report on foreign interference in May, with insights and lessons on how other countries have responded to similar threats to their democratic systems.

Stages of the public inquiry process

How 'foreign interference' is defined

In Canada, the CSIS Act defines foreign interference as “activities within or relating to Canada that are detrimental to the interests of Canada and are clandestine or deceptive or involve a threat to any person.”

The Department of Justice defines it as “deceptive, coercive, and threatening activities [that] target all levels of government, the private sector, academia, diverse communities, and the general public.”

Foreign interference should be distinguished from foreign influence; whereas the latter refers to legitimate activities such as public diplomacy, the former refers to actors such as foreign governments and their proxies seeking to advance their own strategic objectives by, for example, covertly influencing another country’s electoral outcomes or threatening and harming political dissidents in another country’s sovereign territory.

While foreign interference is not a new phenomenon, the scope and scale of the threat have expanded in recent years as a result of globalization, technological advancements, and rising geopolitical tensions. This has prompted other democracies to define or update their definitions and introduce legislative and administrative measures to detect, deter, and defend against the growing threat of foreign interference.

AustraliaForeign interference activities are those “carried out by, or on behalf of, a foreign power” that are “coercive, corrupting, deceptive or clandestine, and contrary to Australia’s sovereignty, values, and national interests.” |

United KingdomForeign interference is “malign activity carried out for, or on behalf of, or intended to benefit, a foreign power” which aims to “sow discord, manipulate public discourse, discredit the political system, bias the development of policy, and undermine the safety or interests of the U.K.” |

United StatesForeign interference is described as “malign actions taken by foreign governments or foreign actors designed to sow discord, manipulate public discourse, discredit the electoral system, bias the development of policy, or disrupt markets for the purpose of undermining the interests of the United States and its allies.” |

Timeline of revelations about Chinese foreign interference

In late 2022, multiple Canadian news outlets began reporting that China had employed a sophisticated campaign to influence Canadian political candidates and voters during the 2019 and 2021 federal elections. The timeline below provides a snapshot of some of the reporting that helped to sharpen Canadians’ awareness of the issue.

- November 2022: Global News broke the story that the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) warned Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of China’s “vast campaign of foreign interference” during the 2019 election, including a clandestine network that provided C$250,000 to at least 11 federal candidates — mostly Liberals — through proxy groups.

- February 2023: The Globe and Mail reported that confidential CSIS documents claim that China employed a “sophisticated strategy” to disrupt Canada’s 2021 federal election. According to these documents, Beijing’s primary goal was to ensure that the election resulted in a minority Liberal government. The leaked documents also suggested that Beijing instructed its consulates to “leverage politically [active] Chinese community members and associations” to urge Chinese Canadians not to vote for Conservative candidates, who were deemed too anti-China.

- March 2023: Global News coverage alleged that Liberal MP Han Dong, whose riding is primarily ethnically Chinese, privately advised China’s consul general in Toronto to “hold off freeing Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor.” Dong has sued Global News for defamation, but nonetheless resigned from the Liberal caucus. He now sits as an independent MP.

- May 2023: Conservative MP Michael Chong, a vocal critic of Beijing’s treatment of its Uyghur Muslim minority, revealed that CSIS had informed him that he and his family in Hong Kong were being targeted by Chinese operatives.

Timeline of government responses

Facing political and public pressure, in March 2023, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau appointed former governor general David Johnston to lead an investigation into foreign interference by China. The timeline below tracks key moments that led to the public inquiry that kicked off in January 2024.

- March 2023: In addition to appointing Johnston to look into allegations of foreign interference, the federal government launched various initiatives to counter foreign interference, including public consultations for the creation of a Foreign Influence Transparency Registry. It also established a National Counter Foreign Interference Coordinator, invested C$5.5 million to strengthen civil society’s ability to combat disinformation, and allocated C$48.9 million over three years to enhance the RCMP’s counter-foreign interference capabilities.

- May 2023: In his final report, Johnston advised against a public inquiry “given the sensitivity of the intelligence.” He also disputed several claims made by Global News and The Globe and Mail, saying that these media organizations misinterpreted confidential materials. While the government initially backed Johnston’s conclusions, the House of Commons rejected the recommendation not to launch a public inquiry and members of the opposition criticized the process’s lack of transparency. All opposition parties voted for Johnston’s resignation in a non-binding motion. In a national survey commissioned by The Globe and Mail and CTV News, 59 per cent of respondents favoured a formal public hearing.

- June 2023: David Johnston resigned from his role as special rapporteur after delivering his final, confidential report to the Prime Minister’s Office.

- September 2023: The Government of Canada established the public inquiryinto foreign interference. The scope of the inquiry — outlined in the Terms of Reference — and the Commissioner appointed to lead it — the Quebec justice Marie-Josée Hogue — were determined by the government, with agreement from all opposition parties.

What — and who — to watch

Even before the public inquiry officially got underway, some groups with a clear stake in the outcome were critical of the process. This includes:

- Opposition parties protesting limits on their participation. Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre has accused the Liberals of “cover[ing] up the truth about foreign interference in our democracy” by initially denying Canadians the right to a “true independent inquiry.” His party has also criticized the limited role they have been granted in the inquiry. Per the Commission’s Terms of Reference, the Government of Canada is provided “an opportunity to fully participate in the Public Inquiry,” meaning it can cross-examine witnesses and access confidential documents. Meanwhile, the Conservatives are granted ‘intervenor’ status, meaning they can only make submissions to the inquiry. Hogue defended this decision by stating that the inquiry should “remain non-partisan and independent.”

- Civil society groups that are unhappy with the involvement of Canadian politicians they say have ties to Beijing. For example, the Human Rights Coalition, a group that represents various diaspora advocacy groups in Canada, has threatened to withdraw over the status of full standing granted to Han Dong and former Liberal MPP Michael Chan, as well as the intervenor status granted to Senator Yuen Pau Woo. Hogue has noted that it is “precisely because there are allegations” against these men that it be “paramount that they be afforded the full range of participatory rights and protections.” On January 31, the Uyghur Rights Advocacy Project (URAP) withdrew from the inquiry, arguing that the process would put victims at risk. The withdrawal by diaspora groups like the URAP is a significant development, as members of these diaspora communities are the most frequent and vulnerable victims of foreign interference activities. The process will need to ensure that there are adequate provisions for their safety and security, including measures to protect their identities so that they do not face further repercussions.

- Foreign governments in question. The Chinese embassy in Canada said it “strongly deplores” the probe, and that there would be “consequences” if Canada does not drop its “ideological bias.” In India, The Economic Times, one of the country’s largest English-language newspapers, has accused the Trudeau government of using India as “a ploy... to deflect attention” from China, whose alleged actions have typically favoured the Liberals.

Conclusion

As the public inquiry on foreign interference continues throughout 2024, it remains imperative that the process be made as transparent as possible, while bearing in mind national security concerns. Commission participants have already called for Hogue to “make every effort” to provide the public with as much information as possible. During the hearings, the Commission requested that CSIS release 13 classified documents as an assessment of how much information the government could share. While some of these documents were readable, others were entirely redacted. Coupled with the fact that this process took intelligence staff 200 hours to complete, it is clear that the Commission will need to use creative solutions to address the challenge of making classified information publicly available.

The Commission’s final report may have lasting effects on Canada’s rule of law — effects that matter to all Canadians. Ottawa will likely look to the strategies employed by allies like Australia, the U.S., and the U.K. as it adopts stronger legislation to counter foreign interference. For example, Canada is already considering implementing a foreign registry, which requires entities lobbying on behalf of other governments to record their activities. Moreover, in November 2023, the government launched public consultations on how CSIS should be modernized to better counter foreign interference, and how the Criminal Code, Security of Information Act, and Canada Evidence Act should be amended to address this growing threat. Recent actions from Public Safety Canada — which announced on January 29 that it would apply monitoring-enhancing measures to upcoming byelections — demonstrate that Ottawa has already begun taking steps to better protect Canada’s democratic processes.

Moving forward, it will be important that Canadians continue to follow — and scrutinize, where applicable — the Commission’s work to ensure that the process and its outcomes effectively serve Canada’s best interests. Countering foreign interference and protecting democratic institutions will be a society-wide effort that involves raising awareness and building resilience. This public inquiry may set the tone for how Ottawa will combat the issue, and how Canadians will rise to the growing challenge of foreign interference.

• Editor: Ted Fraser; Translation: Eva Moreta; Graphic Design: Chloe Fenemore.