Rodrigo Duterte’s six-year tenure as President of the Philippines has been characterized by a leadership style perhaps best reflected in his most well-known project, the War on Drugs. However, as the country gets ready to select Duterte’s successor in the May 9 election, the issue is curiously muted in the campaign discourse, leading us to wonder: What will happen to Duterte’s War on Drugs once Duterte himself is no longer at the helm?

Revitalization through violence?

After serving for 22 years as the mayor of the southern city of Davao, in 2016, Rodrigo Duterte ran for President on a platform of revitalizing Filipino society by combating corruption, crime, and especially the perceived prevalence of drugs and drug traffic. The previous President, Benigno Aquino III, while generally well-liked, was seen as having neglected such issues. Duterte marketed himself as someone who could bring order and safety to Filipino society, much as he claimed to have done in Davao, cementing his reputation as being tough on crime. As a candidate for President, he assured the populace in no uncertain terms that he would rid the Philippines of the scourge of drugs and drug trafficking through violence and force.

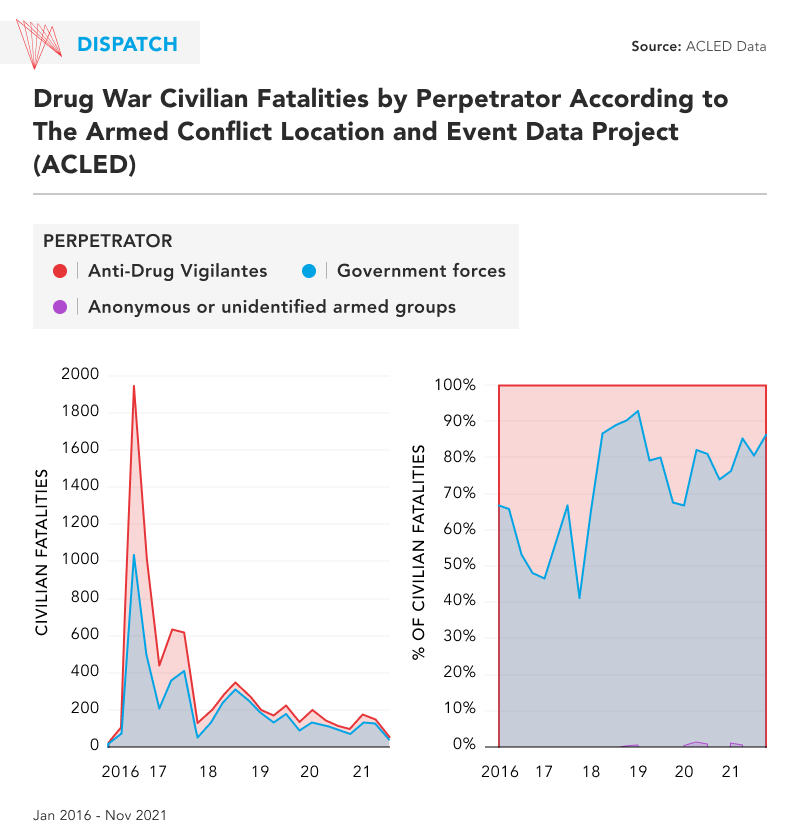

Now, after six years of a Duterte presidency, the role of politicized violence in the handling of crime and criminality has become more tightly woven into the fabric of Filipino society. His War on Drugs has been characterized by high levels of police violence and killing. Not only were police given free rein and subjected to limited oversight in carrying out the War on Drugs, but Duterte himself encouraged extrajudicial violence and vigilantism to aid the initiative. The government claimed that targets of such violence were “drug dealers,” although, in practice, this term was construed broadly by police and disproportionately impacted drug users and petty criminals. Many of the killings were not so much a result of skirmishes that got out of hand but rather a result of Duterte’s exterminatory approach to the people involved in drug crime. Estimations of the death toll have varied, ranging from 6,000 at the very lowest to as many as 30,000. While the first three years of the War on Drugs were the most markedly violent, as its operations continued, so too did the casualties continue to mount.

Now, there is a looming question as to what will happen to the freedom the police have been given in carrying out their operations. A new administration could either maintain the Duterte status quo or attempt to rein them in. Even if the latter option is chosen, it is unclear whether this would even be possible after the almost indiscriminate power granted to police for the last six years.

A strongman and his people

Duterte’s handling of the War on Drugs is consistent with his general political personality. Throughout his political career, both as Mayor of Davao and then as President, the policing of crime has meant the killing of criminals with the co-operation of police and paramilitary death squads. Moreover, while not explicitly connected with the ordering of the killings, Duterte propounded a rhetoric of vigilantism with comments such as “each citizen is now given the right to bear arms . . . and shoot the drug people.” Within the first year of his presidency, for example, he instituted a state of emergency in response to a condition of “lawless violence” after a bombing in Davao city. It gave licence to the Armed Forces and the National Police to “suppress all forms of lawless violence in Mindanao and . . . prevent lawless violence from spreading.” This was not a temporary measure, however, and remained in force for years. His public admission to killing criminals himself further illustrates this leadership style.

Duterte’s authoritarian governing style and anti-drug policies have been accompanied by a centralization of power. For example, he empowered the security forces while undermining democratic checks and balances on the state’s use of coercion. In addition, by 2020, the funds allocated for “opaque intelligence and confidential activities” in the national budget had increased fivefold (P8.28 billion, US$163 million) relative to the 2015 budget (P1.49 billion, US$29 million). Perhaps more concerning, over half of the 2020 funds were dedicated specifically to the Office of the President. Given Duterte’s disposition towards indiscriminate violence and centralizing power, this allocation of funds further exemplifies the institutional decay that has occurred during his tenure and the central role afforded to security forces in his political agenda.

The Duterte government has also impeded attempts at accountability by suppressing dissent and attacking political opponents, journalists, and the judiciary. It further insulated itself through disinformation campaigns that undermined public discourse and “informed political decision-making.” Senator Leila De Lima, for instance, has been imprisoned since 2017 after Duterte alleged that her 2016 senatorial campaign was funded by illicit drug money. Although the President and his administration maintain that the charges are being legitimately put forward by the Philippine judicial system, De Lima and human rights groups remain adamant that the entire situation is politically-motivated retaliation for her attempt to investigate Duterte’s violent drug war. Meanwhile, 2021 Nobel Peace Prize-winning journalist Maria Ressa of news site Rappler also came under attack for criticizing the administration and its actions. Although Ressa had two cyber libel suits dismissed, she remains on bail as she appeals a conviction for another cyber libel case. If upheld, she could be sentenced to prison for up to six years.

The government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic in many ways mirrored its broader attitude toward tackling national issues. The approach had an overtly military tone, with former generals assigned to COVID-19 task forces, the use of law enforcement to enforce COVID policies, house-to-house searches for people infected by the virus, and the relocation of sick individuals to government facilities. Duterte also publicly announced that Filipinos would either have to take the vaccine or be jailed. It is worth noting that these measures do not appear to have been particularly efficacious against the spread of the virus.

Yet, despite the harshness of this approach, Duterte has remained popular with the public, ending 2021 with an approval rating of 72 per cent. Filipinos have also expressed satisfaction with the state of their democracy: In a 27-country Pew Research survey conducted in 2019, they had the second-highest satisfaction rate (69%, as compared to 61% in Canada). Duterte’s continued popularity reflects the degree to which many Filipinos, especially those from the middle and upper classes, are willing to support his policies and tolerate – if not approve of – his governing style. This could provide some insights into the minds of voters in the upcoming election.

Human rights and international accountability

Despite Duterte’s robustly strong approval ratings within the Philippines, as the police began to publish the numbers of those killed in the War on Drugs, there were some groups inside and outside the country that objected to the Duterte government’s conduct. Human rights groups, such as Amnesty International Philippines and the United Nations Human Rights Office, assert that the President’s drug war operations are characterized by a culture of impunity and a variety of human rights violations, including extrajudicial and vigilante killings.

Even as observers warn that democracy in the Philippines continues to backslide, Duterte has disregarded the instruments of international justice, particularly the International Criminal Court (ICC). Following preliminary examinations into his illegal drug crackdown, the President withdrew the Philippines from the ICC’s Rome Statute and stated that the Court would “never take [him] alive.” Nonetheless, the Philippine Supreme Court ruled in July 2021 that any crimes perpetrated after the country’s ratifying date, August 2011, and before its official withdrawal date, March 2019, would be eligible for ICC investigation. Vested with this authority, the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor initiated a full investigation in September 2021. Two months later, however, Philippine government officials requested that the investigation be deferred until they could conduct their own investigations and trials, arguing that the Court may assert its jurisdiction only after domestic legal and judicial instruments fail. Although human rights groups and critics denounced the notion that the administration would legitimately investigate its own alleged crimes, the ICC granted the Philippines its deferral, meaning it will be up to whomever Filipinos choose for their next President to decide how to proceed.

What’s next for the War on Drugs?

By and large, the current batch of presidential candidates has maintained that anti-drug efforts should continue, albeit in a different manner. Bong-Bong Marcos, Vice-President Leni Robredo, Senator Manny Pacquiao, and Senator Panfilo Lacson have all stated that existing efforts have been overly focused on enforcement. Manila Mayor Isko Moreno, for example, is in favour of the policy and noted that he would focus on “drug lords and syndicates,” particularly those from abroad, without violating human rights. Pacquiao maintained a similar position and stated that the targets of anti-drug efforts should be manufacturers and suppliers rather than street dealers. Meanwhile, Robredo has promised to sustain the “same vigour but [utilize] different methods.”

Whereas there is a general consensus that anti-drug efforts must continue, candidates diverge somewhat regarding the role of the ICC. Although four of the candidates (not including Marcos) promised a return to the ICC and demonstrated a willingness to permit an international investigation, there was no consistency in their answers to whether the ICC should prosecute President Duterte. Lacson, for instance, believes that the ICC should prosecute Duterte, while Pacquiao has hedged, stating that prosecution should occur only if there are misdeeds that justify such action. Conversely, Moreno asserted that there should be no prosecution. In what could be an attempt to avoid alienating Duterte’s many supporters, Robredo did not offer a direct answer, stating that she was in no position to take a side. For his part, Marcos said he would not permit any investigations and vowed to be unco-operative with the Court.

As the Philippines continues to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, voters remain more concerned with economic issues, particularly jobs, than they do with accountability or the fate of the War on Drugs. Nonetheless, as misinformation and historical revisionism abound in the Philippines, the risk that the Duterte administration’s actions are forgotten or misremembered will grow. While all the presidential candidates have campaigned on de-escalating the incumbent’s drug war, the culture of impunity established under President Duterte could embolden security forces and vigilantes to act unilaterally and normalize indiscriminate violence. That said, the centralized nature of the Philippine political system may also enable President Duterte’s successor to reel in security forces by leveraging the executive branch’s power and resources. Ultimately, despite fading from the forefront of the country’s elections, it is unlikely the War on Drugs will disappear from the country’s collective conscience. As Duterte exits office with strong approval ratings, Philippine society’s willingness to accept coercive, authoritarian solutions to the country’s problems may spur another era of indiscriminate violence and human rights violations.