Japan’s 2023 parliamentary session began with an alarming statement from Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, who warned that Japan was on the “brink of social dysfunction" due to the country’s rapidly declining birth rate, population, and labour force. A sense of urgency to address these issues swept across the country, leading the central government to prioritize child-rearing policies and increase efforts to support the equality of women and families. One prefecture even released Japan’s first “declaration of overcoming the population decline crisis.”

These policies reflect Japan’s long-standing pattern of retaining its postwar identity as an ethnically and culturally homogenous nation. From the late Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s “Womenomics” to Kishida’s “New Capitalism,” policies directed at mitigating population decline have focused on harnessing the country’s existing underutilized populations — including women, youth, and older adults — and new technologies. However, Japan’s population decline and other demographic challenges cannot be addressed solely by insular social policies and robotic interventions. Is immigration a possible solution?

Currently, Japan lacks a holistic system for immigration and has historically opted to introduce piecemeal migration policies to temporarily fill gaps in the labour market. In contrast to Canada’s unified and coherent immigration system, Japan’s official immigration policies are limited to high-income earners and supplemented by ‘side door’ migration policies for lower-skilled, short-term labour. And while Japan's Ministry of Justice has long been responsible for official immigration, the direction of migration policies is often influenced by multiple government ministries, agencies, and businesses.

Currently, Japan lacks a holistic system for immigration and has historically opted to introduce piecemeal migration policies to temporarily fill gaps in the labour market. In contrast to Canada’s unified and coherent immigration system, Japan’s official immigration policies are limited to high-income earners and supplemented by ‘side door’ migration policies for lower-skilled, short-term labour. And while Japan's Ministry of Justice has long been responsible for official immigration, the direction of migration policies is often influenced by multiple government ministries, agencies, and businesses.

Some pundits present mass immigration as an eleventh-hour solution to Japan’s shrinking labour force, aging population, and declining domestic consumption. It is also suggested that Japan could emulate successful immigration-dependent countries, like Canada, by targeting a yearly influx of one million immigrants to counteract population decline. Japan’s expanding attention to migration-related policies indicates a definitive nod towards recognizing the country’s growing need for long-term foreign labour. Still, questions remain regarding the structural and cultural feasibility of integrating and retaining the extraordinary number of migrants necessary to maintain Japan’s labour market stability.

What do the numbers say?

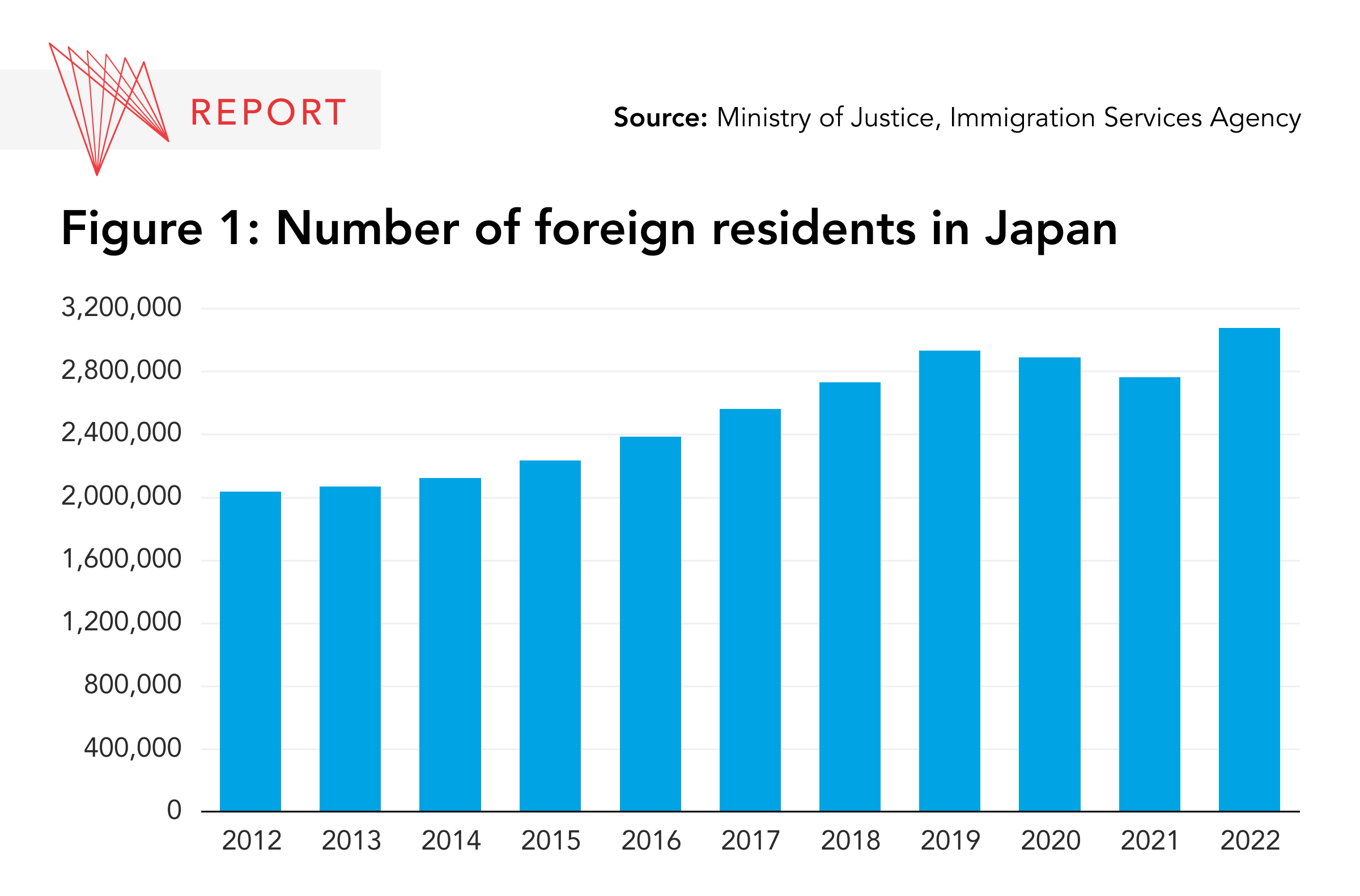

Japan’s population peaked in 2010 at 128.1 million. By 2022, the population had declined to 125.7 million and is projected to fall to 119.1 million by 2030 and 87 million by 2070. Japan’s society is also the oldest in the world, with 28.7 per cent of the population above the age of 64. That number is projected to rise to 38.7 per cent by 2070. At the same time, the country’s birth rate reached an all-time low in 2022, with a fertility rate of 1.26, and only 770,747 births in 2022, the first time this figure has fallen below 800,000 since 1899. While the foreign resident population accounted for a record high of three million people in 2022, the growth has been gradual, only accounting for 2.4 per cent of the total population last year.

These demographic trends are straining the country’s labour force, which has been shrinking since 1993, when its working-age population peaked at 87 million people. By 2040, there will be an anticipated labour shortage of 11 million workers. To offset this gap, Japan would need 647,000 working-age immigrants per year – an incredibly high number. But there were only 115,000 new migrants in 2018, 138,000 in 2019, and 85,000 in 2020, with a slight uptick anticipated post-COVID-19.

In comparison, Canada, which has a comparatively long-standing and highly developed system for attracting and integrating immigrants, recorded 8.3 million former and current permanent residents in 2021, accounting for approximately 23 per cent of the total population. In 2022, Canada welcomed a record 437,000 permanent residents and aims to increase that figure to 500,000 by 2025. In addition, there are 808,000 people in Canada with valid study permits, 551,000 of whom received a study permit in 2022. These figures are some of the highest in the world but are, in fact, lower than the numbers Japan would need to maintain its population. With its unique socio-cultural dynamics, the ingrained idea of homogeneity, and political push-back, it is unlikely that Japan would ever adopt a Canadian-style immigration system or match these intake numbers.

Still, it is undeniable that Japan’s foreign population has been rising. Mainly living in the country's urban areas, they are increasingly becoming a common sight in smaller Japanese cities, towns, and villages. From international students and technical interns to more specialized and high-skilled labourers, Japan’s foreign resident population reached 3.1 million in 2022. By nationality, more than half of the foreign residents in Japan come from China, Vietnam, and South Korea, with significant increases observed in visa categories for technical interns and students.

Foreign residents, even those who are born or whose families have lived in Japan for generations, are often viewed as temporary visitors to what is perceived as an extremely ‘homogeneous’ Japan. But the rapidly declining population is forcing the country to confront the contradictory relationship between the rigid 'Japanese' identity and accepting more migrants, who are rising in number and an increasingly essential component of Japan’s working population.

Balancing perceived homogeneity and growing diversity

While Japan is often viewed as an isolated island country, historically, it has experienced many phases of interaction and integration with peoples in the region and beyond. Notwithstanding the recent rise in foreign nationals who have and continue to contribute to Japanese society, the country’s ‘hidden’ diversity is slowly becoming more visible — and both challenge Japan’s carefully curated self-identity. The Indigenous Ainu people of Japan are continually organizing to revive and pass on their culture and language and assert their inherent rights. Many Burakumin, Japan’s ‘untouchables’ from the country’s legacy feudal caste system, are raising awareness of human rights issues impacting their communities. Uchinanchu, or people from Okinawa Prefecture, formerly the Ryukyu Kingdom, are also working to restore their identity, culture, and language while balancing the strategic military interests of Tokyo and Washington, with their own. Meanwhile, ethnic ‘Zainichi’ Koreans continue to fight for their rights while contributing to, and proudly calling Japan home.

But Japan’s postwar identity remains largely rigid, and diversity widely unaccounted for. Japan does not collect data on race or ethnic identity in its national census, nor does it account for foreign-born mothers in its fertility rate calculations. Meanwhile, naturalizing as Japanese can be extremely challenging, which has left many foreign-rooted children born in Japan stateless. Multiple citizenship also remains illegal, adding to the difficulties of all foreign nationals living in Japan and Japanese nationals living abroad. And Japan’s notion of homogeneity still prevails in popular culture, likely influencing the extent to which the government supports mass immigration or officially recognize Japan’s inherent diversity.

A question of policy

The discrepancy between reality and the Japanese government’s policies have long existed, with scholarly articles from two decades ago suggesting that replacement migration is too taboo a topic for Japanese politicians to meaningfully address. At the time, the debate over demographics and immigration was said to be driven by a sense of crisis, or kikikan, but the economic pressures of the country’s demographic shift may not have been strong enough to drive real policy change.

Twenty years later, the predicted demographic shifts are coming home to roost, with significant pressure on the economy and society at large. The increased kikikan regarding the country’s demographic issues was visible in Kishida’s aforementioned recent social policies, including those for skilled workers, refugees, and international students. These initiatives could point toward the country getting ready for more immigration, while flying under the radar by avoiding framing them as immigration policies to reduce potential backlash.

Japan’s slow-changing policies towards foreign residents have run parallel to the gradual increase in migrants to offset labour shortages. From the late 1970s to early 1980s, Japan acceded to several international agreements, such as the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (1979), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1979), and the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1981), which together led to the extension of Japan’s social welfare system to foreign residents. In 1984, Japan revised nationality and family registration laws, which allowed nationality to also be passed on through the mother, the use of foreign surnames, and the right to choose nationality at the age of 21 for those born with more than one nationality. And in 1990, Japan passed the Immigration Control and Refugee Act, which introduced several ‘side doors’ for unskilled foreign labour through specialized programs such as long-term visas for overseas Japanese descendants and a short-term technical internship program. These instances of Japan’s liberalizing policies, though limited, demonstrate Japan’s willingness to adapt to accommodate the country’s demographic shift.

More recently, several developments have occurred in Japan’s piecemeal migration policies. In February 2023, the Japanese cabinet approved a proposal from the Ministry of Justice for a new visa system to attract high-income earners and high-value graduates. In April, the government began discussing a draft proposal for an initiative to promote study abroad exchanges for Japanese and foreign students, including part-time work opportunities and pathways to residency for the latter. At the same time, a justice ministry panel released a draft proposal recommending the abolishment of the controversial technical internship program; this draft calls for a new system to secure long- versus short-term workers while respecting the human rights of foreign labourers.

April’s developments were followed by the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s (LDP) approval to expand the scope of Specialized Skilled Workers and allow lower-skilled foreign workers to indefinitely renew their residency status in Japan. And in June, the Japanese Immigration Services Agency extended the working program for Japanese descendants from third to fourth generation descendants. Most recently, during the last days of Japan’s ordinary Diet Session in late-June, the government approved revisions to its immigration bill. This included controversial issues such as the forceful deportation of failed refugee applicants, but it also created a new category of “evacuees,” or quasi-refugees, to provide additional protections to foreign nationals fleeing conflict. Again, these policy amendments point to a pattern of change in the country’s approach to immigration.

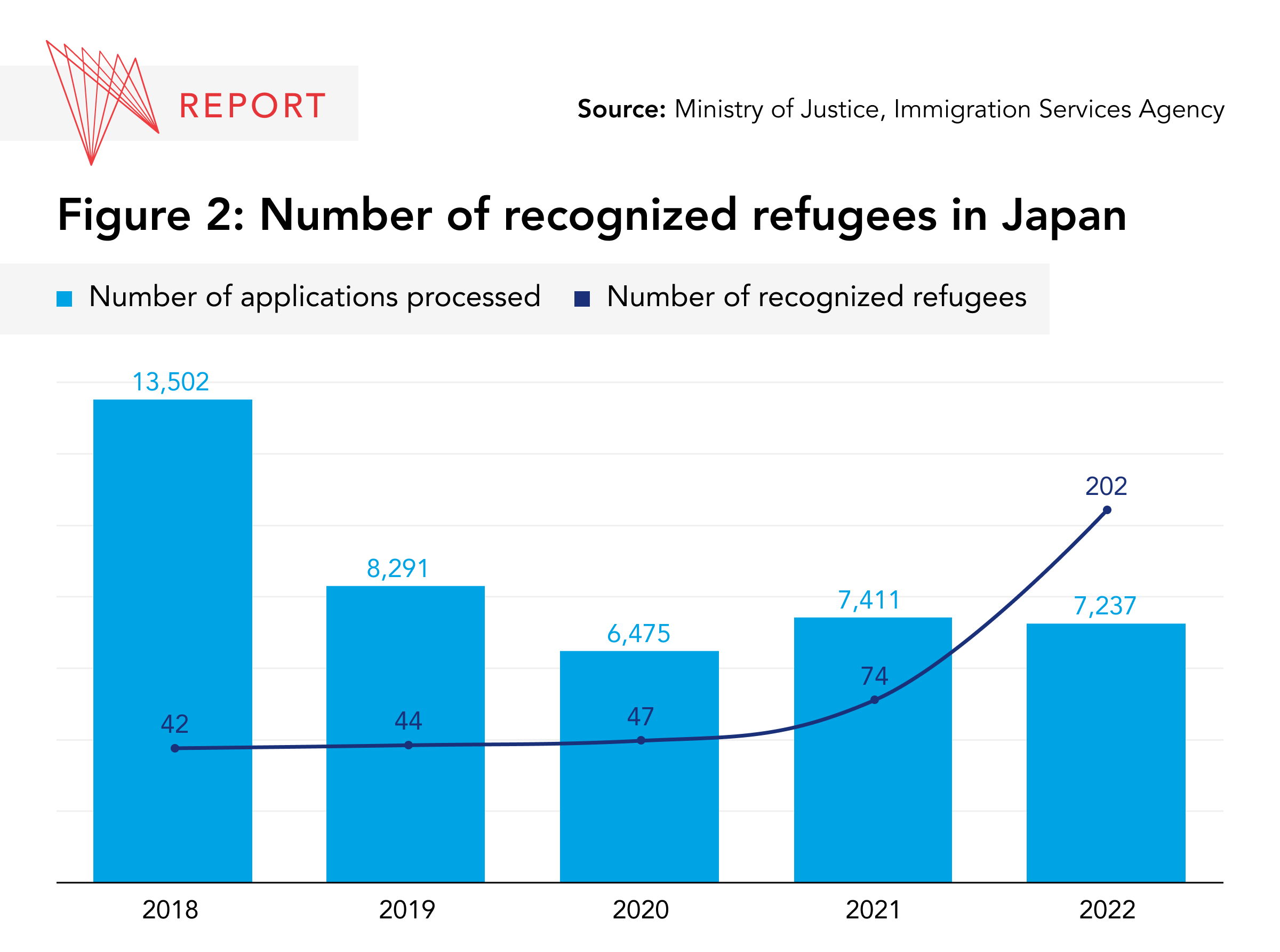

Kishida has made some bold strides, but Japan’s track record on the treatment of migrants and refugees has lagged behind other industrialized nations since the end of the Second World War. For example, Japan’s refugee acceptance rate has been nominal, with only 42 refugees admitted to the country in 2020, 74 in 2021 and a record high of 202 in 2022. In comparison, Canada welcomed more than 75,000 resettled refugees and protected persons in 2022. While Japan has acceded to international human rights conventions, the country has repeatedly been criticized for its lacklustre support of international refugees and, in April, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants stated that the amendments in the immigration bill targeting refugees would “fall short of international human rights standards.”

But translating the international obligations and immigration ideals of liberal democracies into domestic politics has proven difficult. Japan’s ruling LDP consists of competing factions, some of which oppose more liberal policies on subjects like gender, LGBTQ+, and immigration, resulting in a set of piecemeal migration policies, many of which must be passed without consensus, reflecting disagreements between party factions, ministries, and agencies, and foreshadowing problematic implementation.

Although Japan lacks a national immigration policy, the population is visibly diversifying, and subnational governments and civil society groups have often been at the forefront of adapting to the country’s changing demographic needs, playing a critical role in supporting and integrating the non-Japanese population. During the postwar period, civil society groups and local governments were the first to respond to former colonial subjects mainly from the Korean Peninsula advocating for increased rights as long-term permanent residents. Similarly, with the more recent increase of new migrants, some localities have begun creating their own programs, such as translation services, schools accommodating foreign students, or information leaflets for foreign residents to learn about the “Japanese way of life.”

Japan's piecemeal immigration and integration policies, while inconsistent and contradictory at times, showcase a country grappling with the challenges of demographic shifts and may currently be the most politically palatable option for a divided Japan, indispensable for the country's future transformation. But as the labour shortage worsens, will these policies be enough to respond to Japan’s demographic woes?

Can piecemeal policies address Japan's population decline?

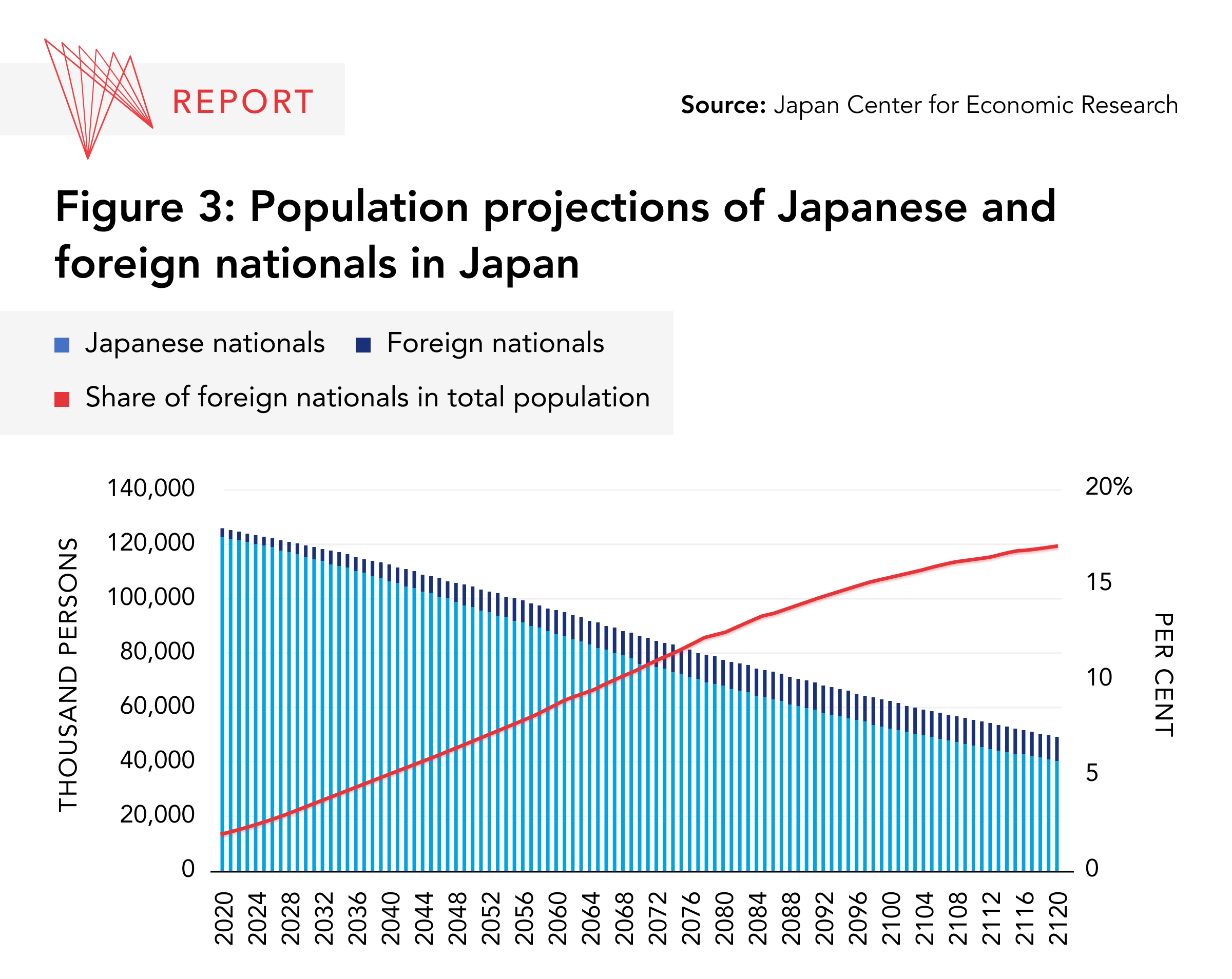

The Government of Japan predicts that the foreign population will peak in 2070 at 9.4 million people before declining to 8.5 million in 2120. Proportionally, foreign nationals are expected to make up approximately 11 per cent of the population in 2070 and about 17 per cent in 2120. These proportional figures are calculated in the context of a smaller Japanese population, indicating Japan’s population, and its labour force, will continue to decline.

If no measures are taken, these figures point towards a potentially alarming situation with an unpredictable and significant change in Japan’s political, social, and economic landscape. Japan’s National Institute of Population and Social Security Research recognizes that “if the predictions come true, Japanese society will change.” This upheaval has been characterized in forecasts that predict the extinction of rural communities and municipal governments, the end of 24-hour convenience stores, a significant home vacancy rate, and the mass closure of services including banks, department stores, and hospitals. At the very least, Japan can expect change in all sectors, including continued attempts to maximize technologies and robotics to offset labour shortages, further changes to Japan’s rigid work culture, increased labour mobility, higher retirement ages to alleviate pressure on the pension system, health care uncertainties, education reform, and increased foreign labour to fill the gaps.

Even in the absence of a comprehensive national immigration policy, Japan will continue to experience migration flows, whether managed or not. If and when large-scale, unassimilated, or adequately integrated immigrant numbers become noticeable throughout Japan, the country could well witness a potential disruption to social welfare, increased human rights abuses, and changes to Japanese society at large necessitating greater protections for foreign residents.

One driver of change for migration-related laws in Japan has been public opinion. Human rights allegations, such as harassment, exploitation, and abuse, against Japan’s decades-old technical internship program, propelled the recent government panel review, which will likely result in the amendment or abolition of the program in the coming months. And activism by non-profit organizations in support of children of illegal residents helped encourage the country’s justice minister to introduce a supplementary policy to ensure the protections of foreign minors born and raised in Japan. The government is also currently discussing the extension and expansion of ‘designated activities’ visas for domestic foreign workers as demand from working professionals and localities increases.

One driver of change for migration-related laws in Japan has been public opinion. Human rights allegations, such as harassment, exploitation, and abuse, against Japan’s decades-old technical internship program, propelled the recent government panel review, which will likely result in the amendment or abolition of the program in the coming months. And activism by non-profit organizations in support of children of illegal residents helped encourage the country’s justice minister to introduce a supplementary policy to ensure the protections of foreign minors born and raised in Japan. The government is also currently discussing the extension and expansion of ‘designated activities’ visas for domestic foreign workers as demand from working professionals and localities increases.

But more pertinent are the struggling voices of Japan’s vast network of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) — accounting for 99.7 per cent of Japanese businesses — dismayed with Japan’s worsening economic situation. Labour shortages and rising wages, combined with Japan’s currency depreciation and dependency on foreign imports, have placed a large burden on SMEs, and many have become reliant on short-term unskilled foreign labour.

Toward more long-term migration strategies

While reactive policies to public opinion are welcomed by many Japanese, as the demographic problems accelerate, the need for longer-term strategic policy planning to deal with the related economic challenges is becoming increasingly prevalent. Calls for the retention of foreign workers have been mounting, but maintaining long-term foreign residents requires substantial change, not only to ease entrance requirements but also to reform Japan’s work culture and society to better integrate foreign workers. Straightforward policy changes may include Japan’s non-competitive wages, notorious work-life imbalance, complex citizenship laws, and general discrimination against and poor treatment of foreign residents. However, while difficult, it will be equally as important to address the country’s pervasive collective identity as a mono-linguistic and culturally homogenous society to foster acceptance within the Japanese psyche and attract migrants to build a life in Japan.

Japan’s postwar constitution ensures a degree of autonomy for the country’s approximate 3,200 subnational governments (prefectures, designated cities, and municipalities), which limits the central government’s power to impose policies on these subnational entities. Combined with a long-established, conservative-leaning political system, Japan faces systemic challenges in becoming a fully-fledged immigration state, and a combination of piecemeal policies remains, at present, the most likely solution.

Nonetheless, greater dialogue and co-operation with prefectural and municipal governments can provide the central government with a more proactive and cohesive pathway to effective policymaking around migration. Prefectural governments have already taken the first steps with the creation of a governor’s group in November 2022 to promote rural revitalization. Among other policies, the group has specifically called for the increase of foreign workers in rural areas. Expert policy advocacy groups such as Reiwa Rincho have also announced plans to open a forum for localities to discuss immigration and integration and identify challenges and prepare municipalities for adaptation to the country’s growing diversity. The Japanese government can strengthen these existing initiatives, bolstering reactive piecemeal policies by incorporating long-term, subnational integration initiatives within national policies as more foreign nationals settle in Japan.

Conclusion: Slow, gradual, and widely undetected expansion of migration

Japan, a ‘super-aged’ society, is among the first advanced industrial economies to face the challenges associated with severe population decline, and the outcomes remain unknown. But as many advanced industrial economies share, or will soon share, similar sets of challenges, Japan provides a case study in facing the dilemma of an aging and decreasing population. While not an ‘end-all’ solution, immigration will undoubtedly continue to increase as one of many responses to population decline. Though the growth may be slow, over time, Japanese society will need to respond to the increasing number of foreign residents. From local education policies to a more consolidated national immigration system, national, prefectural, and municipal governments will have to accommodate foreign residents and facilitate their integration into Japanese society.

The Kishida government seems committed to addressing these demographic issues. But the challenges that lie ahead are so vast, it seems more plausible that Japan will need to manage its population decline rather than completely reverse the trend. This leaves Japan with the opportunity to creatively rethink how to manage its plummeting population, define what and who is Japanese, and reshape the future of the country’s economic growth and sustainability. In doing so, it could position itself as a global leader in addressing significant and fast-paced demographic shifts that are gripping other economies across the world.

Domestically, political opinion regarding immigration remains divided and the integration of foreign residents into Japanese society will necessitate some national policies, especially regarding language. Discrimination against visible minorities is also a critical issue, while social efforts to garner mutual understanding of culturally and linguistically different peoples must be pursued.

Internationally, Japan will need to respond to calls to live up to its responsibility as a democratic country following the rules-based international order to accept more refugees and improve the treatment of migrants. At the same time, Japan will need to compete with other countries to both attract and retain migrants. From non-competitive wages to poor rankings in gender equality and global happiness scales, Japan will need to improve domestic working conditions to entice greater migration.

While the best immigration policies and foreign labour programs cannot completely solve what is an inherently multidimensional issue, they will play a critical role in offsetting population decline and labour shortages, and Japan has many tools at its disposal to reshape its future. Japan will need to confront the situation head-on and implement practical policy solutions to address the challenges that are and will continue to arise with a shrinking population. Successful immigration countries, such as Canada, may provide some examples of new and best practices for Japan. Japan-Canada co-operation on immigration and inclusion-related issues could provide a critical niche for Canada to be an “active and engaged partner to the Indo-Pacific,” as expressed in Ottawa’s new Indo-Pacific Strategy, and a friend and supporter of Japan, our fourth-largest trading partner and a country with which we already share deep historical and people-to-people ties.