The Takeaway

Nepal delivered a hung parliament two weeks after more than 10 million people went to the polls amid a growing economic crisis in the country. While the Nepali Congress-led five-party alliance is most likely to remain at the helm, the alliance is still two seats shy of the 138 seats needed to make a majority and lead the parliament. Incumbent Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba will likely continue for a sixth term, but the leadership faces an uphill battle of expanding the alliance while dealing with a fractured coalition, diluting Deuba’s power. The election results also have a strong bearing on India-China relations and the two nations’ power dynamic in South Asia, as China expands its engagement in the region.

In Brief

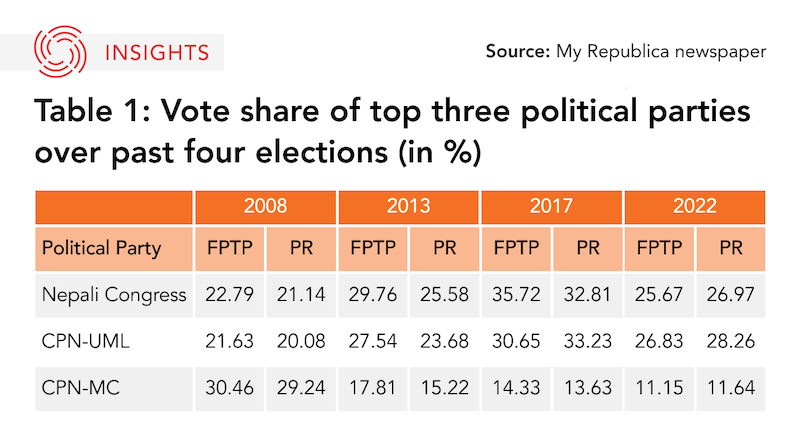

On November 20, Nepal went to the polls for the second time since the promulgation of a new constitution in 2015. The country saw a voter turnout of 61 per cent this time around: a record low compared to the last three elections. A mixed electoral system, 60 per cent of Nepali parliament seats are elected through a first-past-the-post (FPTP) system, and the remaining seats are elected through a proportional representation (PR) system. The results, at the final tally on December 7, indicated that the Nepali Congress-led five-party alliance won 136 of the 275 seats, while the primary opposition, the Communist Party of Nepal-Unified Marxist–Leninist (CPN-UML) led by K.P. Sharma Oli, won 92 seats.

Implications

The 2022 election also saw several young and independent candidates join the race and succeed. This group’s participation underscores the growing public resentment against the national parties and their leaders, corruption, and absence of government accountability, which could also possibly be a reason behind the election’s low voter turnout. The newly elected government headed by the Nepali Congress brings together a spectrum of political ideologies, and attempting to negotiate between these differing ideologies may compound internal instabilities. The fragility of the alliances is best depicted through the number of parallel power-sharing strategies drawn up over the past few weeks. Interestingly, the Nepali Congress ally and third largest party, the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist Centre (CPN-MC), led by Pushpa Kamal Dahal (better known as Prachanda), discussed the possibility of forming a potential left-united coalition with CPN-UML leader and former prime minister Oli.

The political party coalitions in Nepal and their differing alliances with India and China may also impede a cohesive foreign policy. Oli’s party has been more China-aligned, while Deuba’s Nepali Congress is relatively India-aligned. China agreed to several infrastructure projects with Nepal under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a contentious issue for India. On the eve of the elections, Nepal awarded a contract to a Chinese company to build a part of the crucial Terai-Madhesh Expressway, but the Supreme Court of Nepal suspended the contract following a legal challenge posed by Indian bidder Afcons. While, under Deuba, Kathmandu has built closer relations with India, it can’t entirely ignore China and striking a balance between economic and strategic interests will be critical.

What’s Next

- Balancing relations with India and China

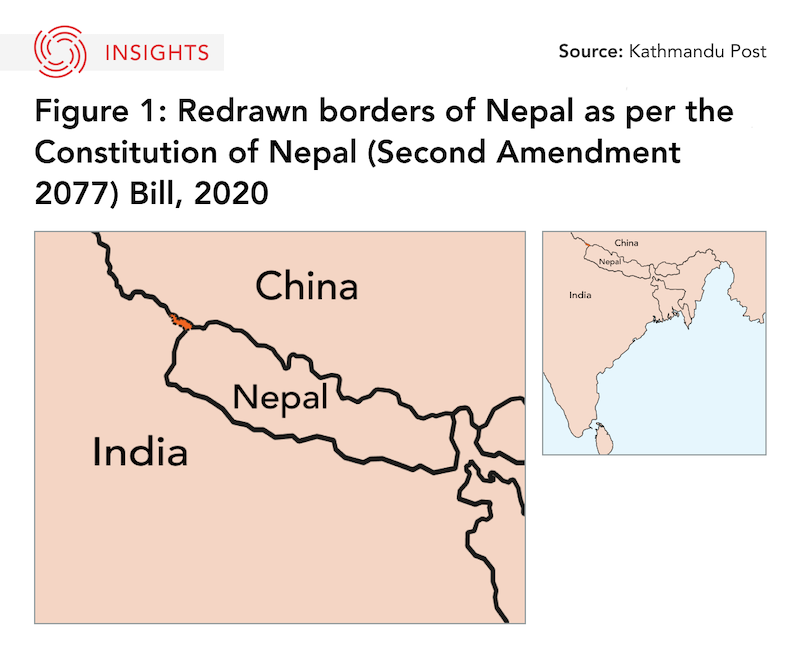

Relations with both China and India have often been rocky for Nepal. In response to India’s release of a new map in 2019 that depicted the Indian-administered disputed region of Kalapani as part of India, the Oli-led Nepali government passed a controversial amendment in 2020, expanding the country’s borders to include three disputed areas with India, including the strategic location of Kalapani, causing increased friction between the two countries. Meanwhile, under President Xi Jinping, China has increased its engagement in South Asia and prefers a Nepali communist regime to combat the U.S.-India influence in the region, which may negatively impact the progress of China’s interests.

- The politics of climate change

Nepal ranks 10th among the countries most affected by natural disasters between 2000 and 2019. On average, there were 47 flood-related events and 21 landslide-related events annually between 2000 and 2020. However, the 2022 election marked only the first time that climate goals figured in political campaigns. Notably, the CPN-UML included vulnerable area mapping and post-disaster relief in their manifesto, while the Nepali Congress committed to increase Nepal’s forest cover to 47 per cent over the next five years (from 41.6% in 2020) and pledged to use local construction materials to prevent floods and erosion. However, none of the parties have outlined a firm strategy for attaining their targets, requiring voters to hold them accountable in the future.

• Produced by CAST’s South Asia team: Dr. Sreyoshi Dey (Program Manager); Prerana Das (Analyst); and Narayanan (Hari) Gopalan Lakshmi (Analyst).