The Takeaway

On July 5, Singapore passed the controversial Online Criminal Harms Act 2023 (OCHA) to effectively combat online criminal activities. The law, targeting scams and malicious cyber activities in particular, empowers the government to proactively remove any illegal online content, account, website, or app. Online content suspected of “provoking” a crime — including offences related to national security, national harmony, and individual safety — can also be removed. Human rights groups have decried the law, arguing that it violates international legal and human rights standards.

In Brief

The law aims to enable the government to proactively disrupt malicious online cyber activities, allowing authorities to act based on ‘reasonable suspicion.’ The government can issue a set of directions to any online service through which a crime is being committed or suspected of being perpetrated. These directions could include ceasing communication, disabling specific content, restricting accounts, blocking access, and removing apps.

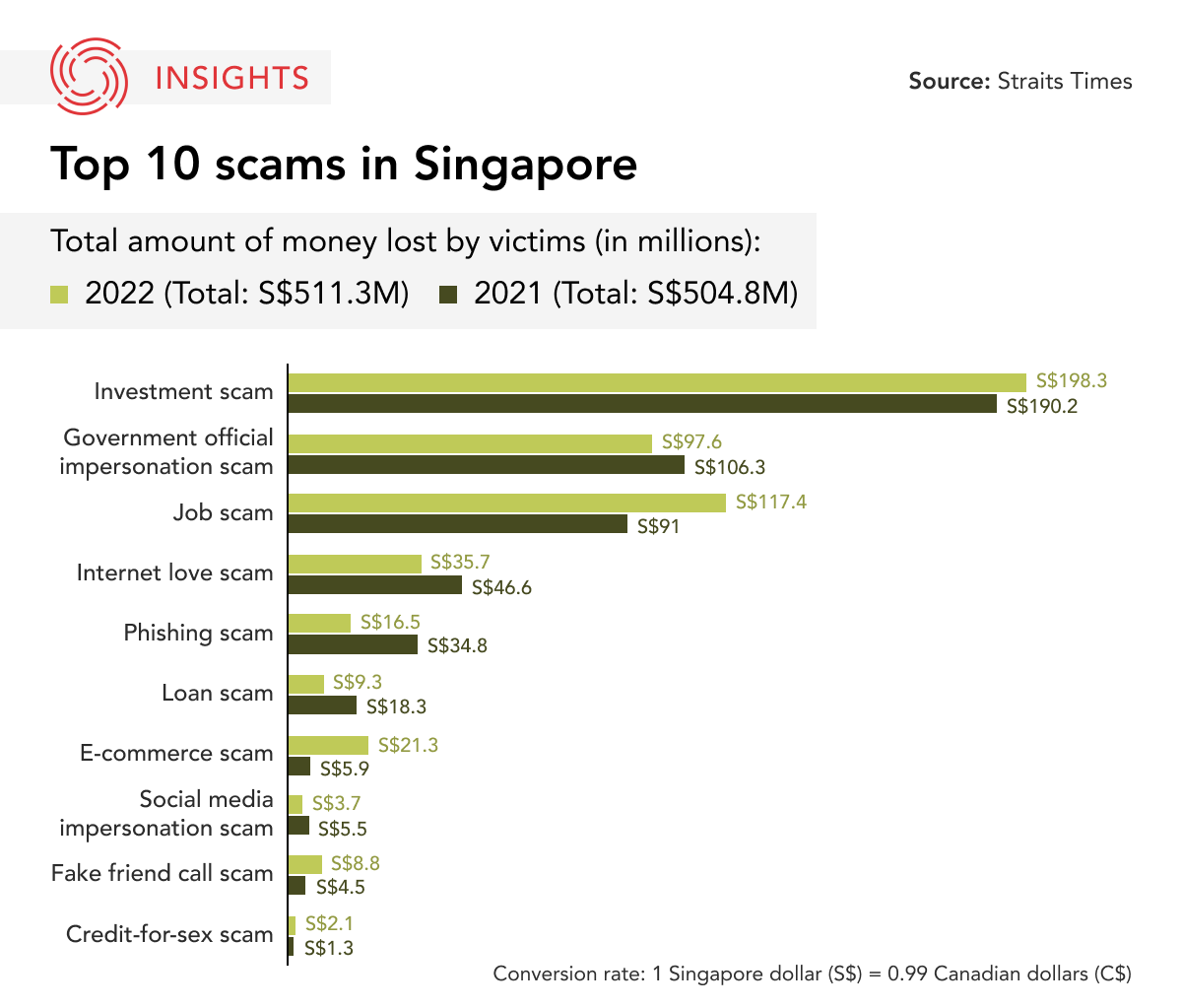

The law puts a strong emphasis on the proactive elimination of suspected scams and malicious online activities. To counter the rapid development of such activities, the law has created a framework to strengthen collaboration with online services. Under this framework, online services suspected of being used for "malicious" activities may be required to abide by the codes of practice issued by the ‘Competent Authority’ (i.e. a designated officer from the Singapore Police Force) to combat malicious activities.

Implications

Online service providers including e-commerce websites may be required under the codes of practice to have systems, processes, and measures in place to work with the government in proactively tackling scams and malicious cyber activities. Online services will be expected to prevent such criminal activities and help the government enforce actions against crimes. For example, e-commerce websites could be mandated to verify sellers and confirm product delivery before a customer is charged for the product.

To tackle online scams and malicious activities perpetrated outside of Singapore, the law empowers the government to issue directions, notices, and orders to entities and individuals based outside of Singapore. If the individual or entity does not comply, they will be prosecuted. The government can also issue “access-blocking orders” to prevent non-compliant platforms — and the malicious content or activity in question — from being accessed by users in Singapore. This suggests that overseas online platforms or services operating in Singapore will be subject to the OCHA and may have to comply with government directives.

Some parliamentarians, including the opposition leader, have questioned the law’s impact on privacy. The government reassured members of parliament that the law would strike a balance between preventing online criminal harm and ensuring privacy. For example, companies will not be asked to break end-to-end encryption in private messaging.

The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development, a regional human rights organization, and CIVICUS, a “global alliance” of civil society organizations and activists committed to strengthening citizen action, have urged the Singaporean government to repeal the act, stating that it infringes upon international legal and human rights principles, including freedom of expression and association, privacy, and participation in public affairs. The groups argue that the government may use the law as an instrument to target dissenting voices, opposition groups, and human rights defenders.

What’s Next

Regional push against cybercrime

- During the 42nd Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit on May 10, ASEAN released a joint declaration on “Combating Trafficking in Persons Caused by the Abuse of Technology,” which appoints relevant ASEAN sectoral bodies to develop strategies and mobilize resources to counter the criminal use of technology in trafficking in persons. While ASEAN did not announce the specific sectoral body in charge of implementation, possible leads could include the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights, the ASEAN Senior Law Officials Meeting, and the ASEAN Commission on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Women and Children. ASEAN is also currently negotiating the creation of a regional extradition treaty aimed at countering transnational crimes such as cybercrime and human trafficking.

Brunei, Cambodia, and Myanmar considering similar laws

- Several other Southeast Asian countries have pushed for the creation of cyber laws. Brunei, Cambodia, and Myanmar are currently drafting their own cybersecurity/cybercrime laws, which may be similar to the OCHA. While each country’s scope may differ, observers believe that all three laws would likely include provisions granting the government (or regulating bodies) the power to access user data and block accounts and websites deemed to be violating the law.

• Produced by CAST's Southeast Asia team: Stephanie Lee (Program Manager); Alberto Iskandar (Analyst); and Saima Islam (Analyst).