The Takeaway

The fifth UN Environment Programme (UNEP) session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-5) on a global plastics treaty, held in Busan, South Korea from November 25–December 1, 2024, concluded inconclusively, postponing talks to INC-5.2 in 2025.

The talks faltered due to sharp divisions between countries advocating legal restrictions on plastics production and oil-producing countries prioritizing plastic waste management. South Korea’s cautious leadership approach also drew scrutiny, raising questions about its industrial priorities and commitment to global environmental goals.

In Brief

- Global efforts to curb plastic pollution began at the UNEP Assembly in February 2022. After four prior meetings in Uruguay, France, Kenya, and Canada, INC-5 extended negotiations to December 2 but failed to reach a consensus, hindered in part by the tight timeline between COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan (November 11–22), and the UNEP FI Global Roundtable (December 10–11) in Geneva, Switzerland.

- INC-5 drew over 3,300 participants, including 440 observer organizations, delegations from 170 countries, and 220 lobbyists, predominantly from petrochemical companies. Greenpeace activists staged a visual protest with a 30-metre banner reading “Cut Plastic Products Now” and featuring a giant eye composed of portraits of 6,472 citizens across 190 countries, symbolizing global scrutiny and public demand for action.

- Activist efforts and high expectations clashed and contrasted with strong resistance from oil-producing nations, reflecting ongoing divisions over limiting plastic production, prioritizing waste management, and securing financial commitments — issues similar to those seen at COP29.

Implications

The fierce debate at INC-5 exposed a fundamental divide. Countries such as Fiji and Panama, as well as the European Union, pushed for binding restrictions on plastic production. Oil-producing countries — such as Iran, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia — prioritized waste management and insisted that delegates base discussions on the original 77-page draft instead of a condensed 17-page ‘non-paper’ introduced to streamline negotiations. Focusing on the longer draft ultimately delayed progress at INC-5.

Russia rejected any form of production limits, while China adopted a strategic, measured stance, signalling openness to polymer regulations — in contrast with the U.S., which promoted voluntary national action plans to avoid binding commitments.

Although progress was made in clarifying national stances, South Korea’s ambiguous and passive role exemplifies the delicate balancing act faced by major plastic-producing countries. As a member of the High Ambition Coalition (HAC), which advocates for stringent measures, South Korea’s reluctance to endorse the Panama Statement, signed by more than 100 countries advocating production cuts, drew criticism. Seoul’s failure to assert leadership in Busan reflects broader tensions between economic dependence on petrochemicals and growing global expectations for environmental responsibility. South Korea’s approach highlights the challenges for countries in reconciling domestic priorities with international environmental expectations in the face of entrenched economic and geopolitical interests.

The talks revealed the overwhelming influence of 220 fossil fuel and petrochemical lobbyists, who overshadowed civil society groups and steered discussions toward industry-favoured positions. This dominance highlights a systemic imbalance, where profit-driven agendas thwart efforts for binding agreements. This dynamic not only reflects the scale of corporate influence but also raises critical questions about the effectiveness of multilateral frameworks in addressing environmental crises.

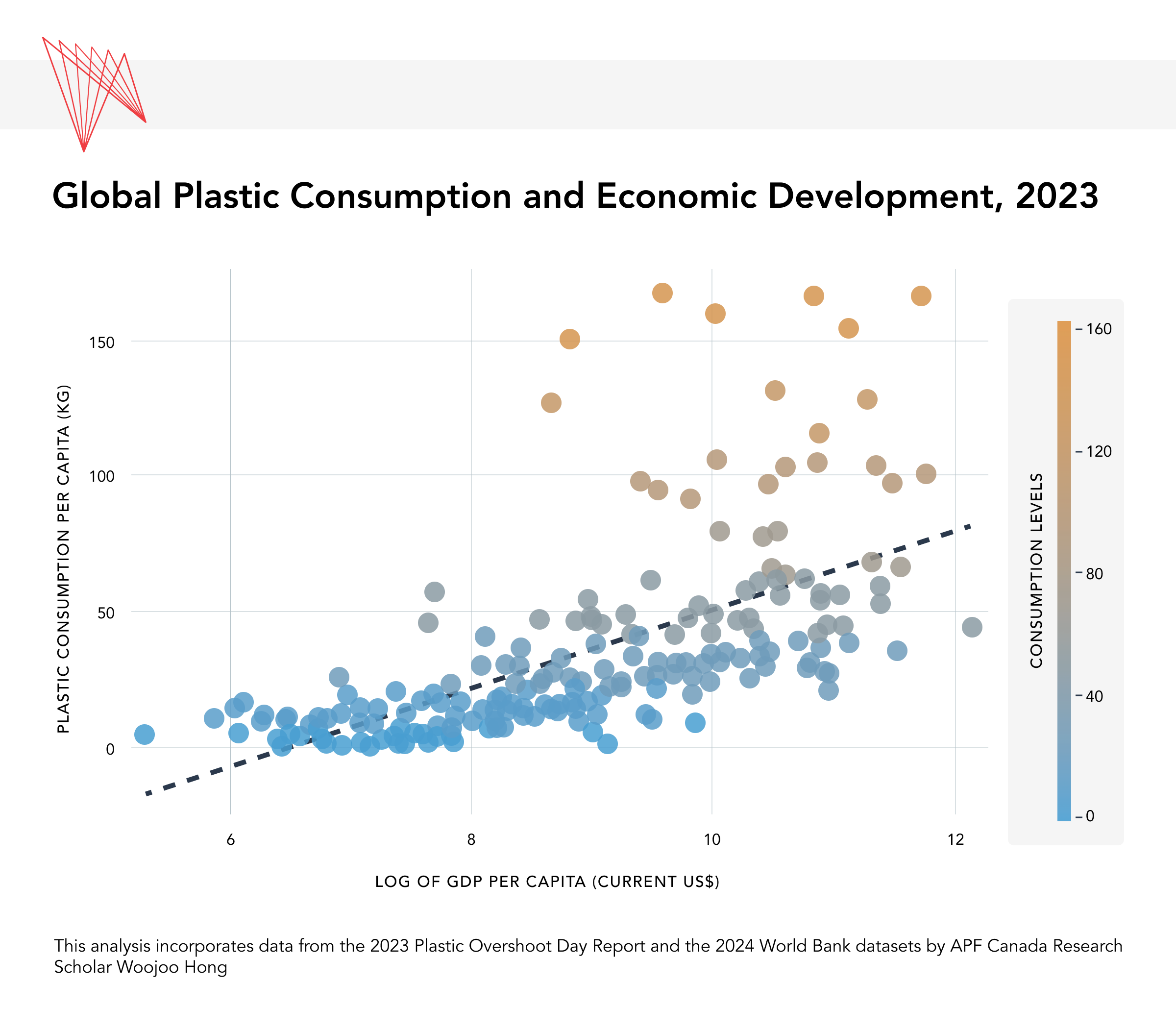

The graph above shows a clear positive correlation between GDP per capita (current US$) and plastic consumption per capita (in kilograms), indicating that wealthier countries consume more plastics. This trend highlights a shared responsibility: high-consuming developed countries must address their role in driving demand, while collaboration with major plastic-producing countries is essential for implementing sustainable solutions to plastic pollution.

What’s Next

1. Renewed talks

INC-5.2, though unscheduled, will test whether countries can overcome the entrenched divide between advocates of plastic production cuts and those prioritizing waste management. Without a clear roadmap addressing these tensions, the risk of repeated stalemates looms large. Progress will require reframing the debate to bridge economic priorities and environmental imperatives rather than perpetuating a binary conflict.

2. Canada’s role

Canada, as a member of the HAC and the host of INC-4, continues positioning itself to leverage its influence in pushing for meaningful outcomes. At INC-4, Canada introduced the Federal Plastics Registry to track plastic production and lifecycle. However, its ability to lead will depend on balancing diplomatic partnerships with proactive advocacy. The key challenge for Canada lies in translating environmental commitments into action without alienating key economic partners.

3. Trump’s influence

The return of Donald Trump to the White House could derail momentum for a robust global environment treaty, given his administration’s historical rollback of multilateral agreements and support for fossil fuel industries. This suggests that other countries must form resilient coalitions to maintain progress; global environmental leadership must diversify beyond reliance on U.S. support to sustain long-term negotiations.