This report is the first in our six-part series on Asia’s rapidly advancing space programs and their implications for Canada. The series features one report each on China, India, Japan, and South Korea, touching on what we know about their strengths and objectives, as well as their commercial space sectors. The series concludes with a spotlight on Canada’s space program and what this ‘revolution’ in space activity might mean for its own ambitions.

This first report introduces readers to some of the main actors and issues, including the need for a rapid revamping of the system of global governance for ‘the final frontier.’

The global space industry is undergoing a significant transformation. Whereas it was once “the preserve of the governments of a few spacefaring nations,” it now involves a greater number of actors engaged in a widening range of activities. The actors include new countries, the private sector, academia, and even citizens who are, for example, making advancements in military and security intelligence, monitoring climate change, improving navigational capacity, or setting up space tourism businesses.

Asia is a major factor in this revolution: China, India, Japan, and South Korea have all expanded their national space programs and actively nurtured their commercial space sectors with investment incentives. For example, over the past decade, the Chinese government has invested an impressive C$2.5 billion to develop its commercial space sector.

This increase in actors and activity is leading to greater co-operation and greater competition. International agreements for global space governance, however, have not kept pace. Canada has its own ambitions for an expanded space program, and thus will need to understand the various Asian actors’ objectives as it participates in discussions about the future of global space governance.

This six-part series will provide an overview of national and commercial space programs in Asia, highlighting the implications for Canada as it looks to advance its own space sector. The series will conclude with a short report that focuses specifically on Canada’s space program.

The commercialization of space

One of the most significant recent developments in the space race is that it is no longer the exclusive domain of national governments. This is largely because the barriers to entry have been lowered with improved technologies that enable the reusability of rockets, the miniaturization of satellites, and the mass production of space objects.

Commercial actors such as SpaceX (U.S.), Blue Origin (U.S.), Galactic Energy (China), MDA (Canada), and Skyroot (India) are even developing their own independent launch capabilities — one of the most notable barometers of the booming space industry. Some of these companies have launched mega constellations made up of hundreds or even thousands of satellites, while others are seeking to extract resources from asteroids, Mars, and the moon.

The commercialization of space has transformed the way national space agencies operate, with many trending towards public-private partnerships. NASA, for instance, has outsourced the orbital and lunar transport to SpaceX and Boeing, and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has partnered with a domestic private defence contractor, Alpha Design Technologies, to construct satellites for its navigation system.

These various players are contributing to the global space economy. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development defines the global space economy as “the full range of activities and the use of resources that create value and benefits to human beings in the course of exploring, researching, understanding, managing, and utilising space.”

These resources potentially include lunar soil, water, and minerals, some of which will facilitate space exploration beyond the moon. The value of this economy was estimated to be C$632 billion as of 2021, and some estimate that total revenues could surpass C$1 trillion by 2030.

The global market for space-launches alone is projected to more than double to about C$27 billion by the end of this decade, with more countries — including Canada — greenlighting commercial space launches to incentivize more private investment and innovation.

Many Asian powers are also stepping up. For example:

- China conducted one-third of the 180 successful liftoffs carried out globally in 2022, and it is planning 100 space missions for 2024.

- Between 2024-25, India is set to conduct 30 launches. In 2023, India, placed seven Singaporean satellites into orbit in a single launch.

- Japan’s launch vehicle, H-IIA, has had a near-perfect success rate, making 45 liftoffs over the past two decades. In February 2024, it was replaced with the successful H3 rocket.

- South Korea launched a domestically made rocket and launch vehicle in May 2023, becoming the seventh country to do so.

- A significant number of reliable spaceports — ground-based facilities that can launch orbital objects such as satellites — are based in China, India, Japan, and South Korea.

Missing from this list, of course, is Russia. The former Soviet Union dominated the early decades of the space race. However, between 2018 and 2021, funding for Russia’s national space agency, Roscosmos, dropped about C$320 million, impacting its space missions and the quality of its space technology. Similarly, since the onset of the Russia-Ukraine war in 2022, the number of orders from European states for satellite launches by Roscosmos has tumbled about 90 per cent. And the Soyuz spacecraft, which used to transport astronauts to the International Space Station, has suffered from coolant leaks on multiple occasions — another indication of Russia’s faltering reputation as a reliable space power.

Nonetheless, Russia remains an important player; similar to its collaboration with China in the Arctic, the two countries have fostered closer ties in space. In March 2021, their space agencies signed a memorandum of understanding to construct an International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). Other members of the ILRS include Pakistan, Azerbaijan, and South Africa. On March 5, Roscosmos announced that, together with the China National Space Administration (CNSA), it intends to construct a nuclear power plant on the moon by 2035 with the hope that it may eventually support a settlement. The U.S. has cautioned against the move, saying a rigorous evaluation of the reactor’s safety would be required.

By comparison, the India-China dynamic in space has been more competitive and is focused on testing anti-satellite weapons and moon landings. Thus far, China is well ahead of India, as it already owns and operates the Tiangong Space Station, which could rival the soon-to-be-retired International Space Station.

But India is trying to catch up and plans to have its own space station — the Bharatiya Antariksh Station — by 2035. (The China and India programs, and the competitive dynamic between them, will be addressed in future reports in this series.) India is also finding ways to work co-operatively with others; on the upcoming 2025 LUPEX mission, Japanese and Indian space agencies will work together to assess water resources in the lunar south pole using the recently launched Japanese H3 rocket.

The benefits and risks of increased space activity

This proliferation of space actors and boom in activity create both substantial benefits and risks. On the benefits side, the involvement of non-state actors has been credited with reducing costs by driving innovation. U.S.-based SpaceX, for instance, pioneered the first reusable rocket, Falcon 9, which has significantly reduced the costs of space launches. NASA’s space shuttle would have cost C$74,000 per kilogram to launch to earth’s low earth orbit, whereas the Falcon 9 cost C$3,700 per kilogram.

The risks, meanwhile, include the potential collision of space objects and the orbital overcrowding that results from an increase in space debris. Kessler syndrome is the increasingly likely scenario in which a high density of satellites in Earth’s orbital zone could result in collisions. Those collisions could produce more space debris that, in turn, would increase the likelihood of even more collisions. Another risk is that the growth of satellite constellations, which have been found to obscure some kinds of astronomical observations, will impede the view of deep space and thus our ability to learn from it.

Also of concern is the increase in pollution from the rocket launches and the disintegration of deorbited satellites that could damage the earth’s ozone layer. One study found that a tenfold increase in the number of rocket launches could raise stratospheric temperatures by up to 2 C, further disintegrating the ozone layer. Additionally, rocket-induced soot was found to warm the atmosphere about 500 times as much as soot emitted from airplanes. Satellites also create pollutants, as they disintegrate in the earth’s atmosphere once they are deorbited. While the long-term impact of these activities remains unknown, the need to ensure the sustainable development of space becomes urgent, especially as this magnitude of space activity increases.

The need for stronger governance

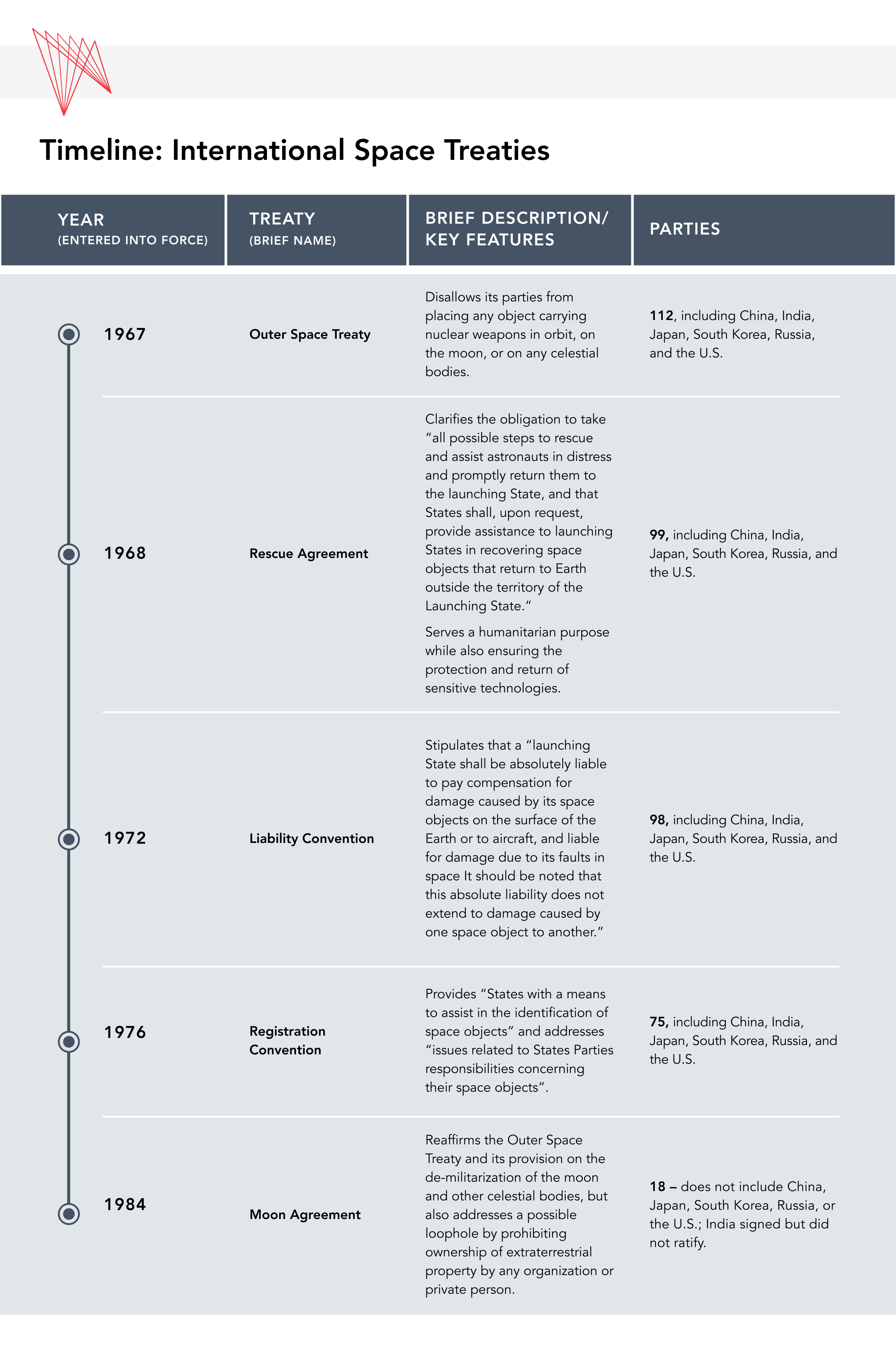

There are currently five binding international space treaties adopted by the UN General Assembly. In addition, there are several non-UN intergovernmental treaties, such as the International Space Station Agreement, and hundreds of regulatory instruments governing space activity. Nevertheless, the development of global space governance has stagnated over the years and has not kept pace with the rapidly advancing space technologies and activities.

When the 1967 Outer Space Treaty was negotiated, the U.S. and Russia were the key spacefaring countries. This treaty set the core content and governance approach for the subsequent four treaties that were negotiated based on consensus between 1967 and 1984 during the Cold War and against the backdrop of a different set of political anxieties between the two major spacefaring states.

International Space Treaties Links:

While China and India are parties to most of these agreements, they were not major space players at the time, and thus were not significantly involved in negotiating any of these treaties. Nor was the role of non-state actors taken into consideration in crafting these treaties.

There are also more recent multilateral initiatives, happening outside the UN system, such as the U.S.-led Artemis Accords. These Accords, while non-binding, reinforce the Outer Space Treaty based on the U.S.’s interpretations of resource extraction permitted under the treaty. Signatories of the Accords include Australia, Canada, India, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. China has not signed the Accords, primarily due to objections to the Wolf Amendment, passed by the U.S. Congress in 2011, which prohibits NASA from working with its Chinese counterparts.

It is important to note that the key international treaty governing the moon, the 1979 Moon Agreement, has been ratified by only 11 countries and is often seen to be a failed treaty due to its relative lack of acceptance, particularly among major spacefaring nations such as the U.S. and China, which hope to eventually be able to exploit lunar resources. The only Artemis partner that has ratified that instrument is Australia, and it remains to be seen how Australia would navigate its obligations laid out under the Moon Agreement and its bilateral activities under the Artemis Accords.

China, which has been wielding much greater influence in space governance, has contested the Artemis Accords, calling it a colonial move that would allow the U.S. to claim lunar sovereignty. With the global order shifting as tensions between China and the U.S. mount, the Outer Space Treaty (which has not been violated since its adoption) is coming under strain as new technological applications and their associated risks grow.

Additionally, in 2022, China chaired the first Joint Committee on Space Cooperation within the BRICS, an intergovernmental forum comprising Brazil, China, India, Russia, and South Africa. The forum focused on data-sharing from remote sensing satellites. In 2014, Russia and China also attempted to pursue a draft Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space, the Threat or Use of Force against Outer Space Objects.”

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), comprising Australia, India, Japan, and the United States, issued a joint statement in 2021 on the sustainable development of outer space. Two years later, Quad members announced their commitment to deepen collaboration on a number of other areas, including the enhancement of supply chains to support commercial space activity and an increase in data-sharing for better space situational awareness to mitigate the risks of space collisions.

As others in Asia, such as Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia, and Taiwan, enter the space industry, the role of the more established regional space actors, namely China, India, Japan, and South Korea, in driving the region’s space ambitions will become important.

Looking ahead to a new era of global space governance

Today’s increasingly multipolar world is starkly different from the one in which the Outer Space Treaty was negotiated, when just two states — the U.S. and Soviet Union — dominated this domain. The growing diversity and influence of spacefaring states such as China and India will need to factor into new international legal frameworks governing space.

It could be argued that achieving consensus on a binding treaty in the current international environment may be far more challenging than it was half a century ago. Efforts to reach consensus in early 2019 on a peace treaty in space within the UN-based Group of Governmental Experts failed when 25 nations, including major spacefaring ones, were unable to reach consensus due to the proposed language on deploying military hardware in space — a balance of power issue, particularly between the U.S., Russia, and China, that has plagued international space negotiations for decades.

Nevertheless, despite legal or political disagreements on other issues, co-operation in space has in the past been possible, and sometimes even extensive, between powerful states.

Perhaps against all odds, the U.S. and Russia continue to co-operate on the International Space Station. While the U.S. has tried to box out new competitors, specifically China, non-binding instruments have enabled co-operation to continue even among rival states. In some ways, such an approach may be contributing to the resilience of the international legal regime governing space during times of uncertainty over political or scientific issues.

Canada, which became the third spacefaring nation in 1962 with the launch of its satellite, Alouette I, is well-positioned to play a greater role in global space governance, including in encouraging commercial partnerships.

Aside from being an active partner in the International Space Station and in the Artemis Accords, it is estimated that Canada’s space economy may be valued at C$40 billion by 2040. As investments and technological innovation grows exponentially in Asia, opportunities are likewise presented for Canadian government and private actors to tap into the emerging market.

• Editors: Erin Williams, APF Canada Senior Program Manager; Vina Nadjibulla, APF Canada Vice-president, Research & Strategy.