The Takeaway

At the heart of Sri Lanka’s economic woes, which caught the attention of the international community in 2022, is the country’s foreign debt crisis. At the turn of the year, the island nation is more dependent than ever on international assistance as it pursues austerity measures to secure International Monetary Fund (IMF) funding. The Sri Lankan government hopes to revive its domestic industry and stabilize the economy in 2023, while fending off public criticism.

In Brief

At the end of December 2022, Sri Lanka saw a record 20,000 civil servants retire, due in large part to the government’s move to reduce the retirement age from 65 to 60 years. Within the first week of 2023, a top government official said that the positions would not be refilled, leading to a recruitment freeze in the public service. The freeze is widely considered part of the government’s push to secure assistance worth C$3.9 billion (1.05 trillion Sri Lankan rupees) from the IMF, which, in its assistance package, includes conditions like increasing financial transparency and reducing corruption.

Implications

In April 2022, Sri Lanka defaulted on its foreign debt for the first time. Over the next two months, the country tumbled into chaos as public protests against the then-government turned violent, eventually forcing the president, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, to flee the country and resign. These developments were unprecedented in Sri Lanka’s history. They were triggered by some short- and long-term factors, including economic mismanagement by the Rajapaksa dynasty, tax breaks for higher-income individuals, a 2021 chemical fertilizer ban that led to low crop yields, and a tourism slowdown. However, at the root of its troubles is Sri Lanka’s unsustainable foreign debt burden.

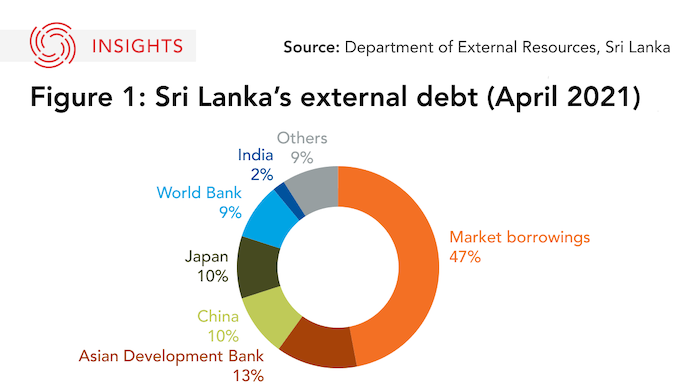

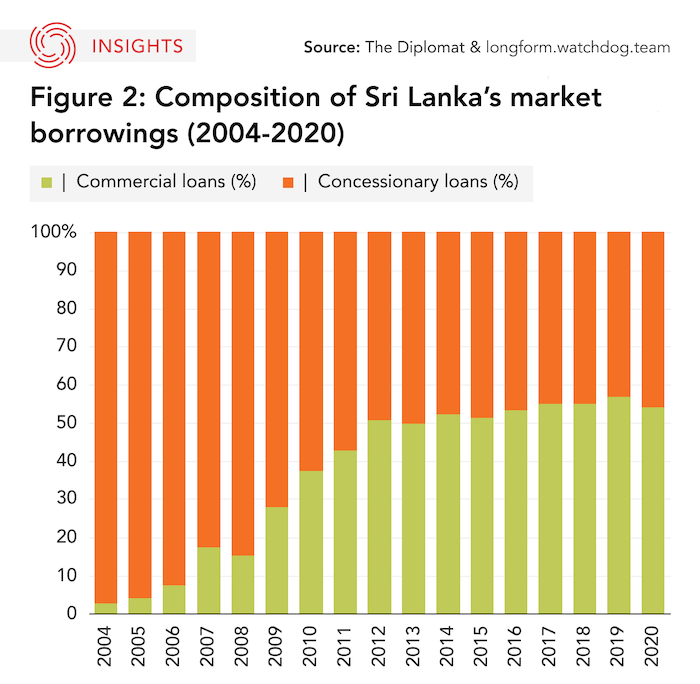

Nearly half of the country’s external debt is through market borrowing (Figure 1), and a large portion of this borrowing is in the form of commercial loans. Until the 2000s, a major slice of Sri Lanka’s borrowing was in the form of concessionary loans with either more lengthy 'grace periods,’ lower-than-market interest rates, or a combination of both. But when the World Bank promoted Sri Lanka to a “lower-middle-income economy” in the early 2000s, the country had to resort to commercial loans with shorter grace periods and higher interest rates, and their share kept increasing over time, planting the seeds of future disruption (Figure 2).

With no concomitant increase in trade or foreign direct investment inflows as a percentage of GDP, Sri Lanka continued to borrow more money from external lenders at higher interest rates to repay interest on outstanding loans. This increased the total debt amount and left little to be invested back into the country to build economic opportunities and social security.

What’s Next

1. IMF assistance and debt restructuring

Sri Lanka’s talks with the IMF are yet to conclude. Following the IMF’s guidelines under the Extended Fund Facility, the funding is contingent on Sri Lanka acquiring assurances of debt sustainability from its creditors. Talks have somewhat stalled due to China’s reluctance to join other bilateral creditors to negotiate on a common platform. President Ranil Wickremesinghe hopes to receive the creditors’ commitments by February 4, 2023, when Sri Lanka will celebrate 75 years of independence from British rule. Later that month, the country will likely see its first local elections since the 2022 debacle, which will also be a test for the current government.

2. Progress on human development compromised

According to Human Rights Watch, the economic crisis has brought Sri Lanka to the brink of a humanitarian crisis, in which 28 per cent of the population is ‘food-insecure.’ The poverty rate also doubled in 2022. Inflation on food prices has impacted child malnutrition rates and exacerbated health issues, while many Sri Lankans remain unable to afford essential health services. While the IMF deal calls for mitigating the impact of the crisis on the poor, it requires structural adjustments that could result in cuts to social sector spending in the years to come.

3. Reviving the tourism sector

The tourism sector, constituting around 12 per cent of Sri Lanka’s GDP and acting as an important source of foreign exchange, has declined since the 2019 Easter Sunday terror attacks, a drop compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Sri Lankan government has accelerated its efforts to attract tourists and revive the industry. However, record outmigration and a brain drain caused by the political and economic crisis may leave the industry with less skilled staff.

• Produced by CAST’s South Asia team: Dr. Sreyoshi Dey (Program Manager); Prerana Das (Analyst); Narayanan (Hari) Gopalan Lakshmi (Analyst); and Silvia Rozario (Analyst).