The pervasive and persistent COVID-19 pandemic continued to shape many developments in the Asia Pacific in 2021. While the year behind us saw the advancement of new vaccines, the spread of variants of concern, most notably Delta, ensured that 2021 remained turbulent. And the risk presented by the most recent variant, Omicron, could delay reopenings and further impede economic recovery in 2022. But with turbulence comes the opportunity for reflection, change, and paving new paths. The same holds true in the context of Canada-Asia relations.

APF Canada’s Asia Watch newsletter has been a cornerstone of our work tracking and reporting on uncertainties and trends in Asia that impact Canadian interests in the region. Since its inception in 2019, we have produced 346 Asia Watch newsletters with 1,384 unique stories analyzing social, political, economic, and environmental issues in every economy in the Asia Pacific.

This work allows us to turn our gaze to the coming year and discuss trends for 2022. This special year-end dispatch highlights ten issues that deserve special attention and will help Canadians better understand the region today and in the coming year.

The second half of 2021 saw economies throughout the Asia Pacific attempt to move from managing the pandemic to emerging from it. This pivot was mainly due to the broader distribution and uptake of vaccines and specific health-related policies, programs, and treatments. But the Omicron variant has put much of the world’s reopening optimism on hold. As we analyze how COVID-19 will shape the Asia Pacific in 2022, we see increasingly equitable vaccine distribution and increased investment in health sectors that promise new types of vaccines for COVID-19 and other health applications.

Pandemic-related disruptions affected everyone, although not equally. They exacerbated inequalities and barriers for the poor, women, youth, Indigenous peoples, and other underrepresented groups. Welcoming the new year with so much uncertainty may mean that economic-related policy choices will remain limited to short-term measures, making 2022 a challenging year for inclusive growth priorities.

Young people also have faced significant challenges, especially around employment. Labour disruption led many to join the growing gig and platform economies, leave the cities and return to their hometowns, or take up less hectic lifestyles. Will this ‘reverse migration’ be a temporary or permanent situation? 2022 will be telling.

While inequalities are rising globally, they are particularly acute in China. The Chinese Communist Party has begun asserting new types of control over the country’s economic development under its latest campaign, ‘common prosperity,’ to mitigate widening inequality. While this is a long-term initiative, 2022 should provide the first hints of how Beijing plans to balance the various interests and policies that are entangled in redistributing wealth among the people of China.

Amid ongoing protectionist surges worldwide, free trade in Asia will expand in 2022, when the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) enters into force on January 1. How will the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and RCEP, two of the world's largest free-trade agreements, cohabit and compete?

Western big tech companies were in the spotlight throughout the region in 2021, often for all the wrong reasons. While many of Asia’s economies rely on social media platforms for everyday business and government operations, application outages and criticism of social media’s toxicity and polarizing effects erupted as prominent issues this year. In 2022, will more Asia-built tech platforms emerge, and will new regulations rein in big tech or create new, unintended challenges?

On the security side, 2022 will be a critical year in Asia. Increasing militarization in East Asia could escalate the risk of violent confrontation in 2022. While some see cause for cautious hope in the problematic situations in Myanmar and Afghanistan, others see the potential for further degeneration that could lead to exacerbated regional insecurity and humanitarian crises. And with climate change now recognized as an aggravating factor for myriad security issues, the coming year will be an important one for seeing how the Asia Pacific implements policies, measures, and practices to meet or exceed internationally-agreed goals.

Enjoy our 10 Things to ‘Asia Watch’ in 2022!

1. Social Recovery

Throughout the Asia Pacific in the latter half of 2021, as countries began to meet their vaccination targets, many also shifted their focus from managing the COVID-19 pandemic to emerging from it. Countries that had previously pursued a ‘zero-COVID’ strategy, including Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam, announced they were transitioning to a strategy of ‘living with COVID.’ This boosted hopes that, after two years, a return to some kind of normal might finally be on the horizon in 2022. But no sooner was this ‘living with COVID’ strategy articulated than challenges arose, as loosened restrictions were met by sharp increases in case counts and hospitalizations. Meanwhile, China remains the only major country still pursuing a ‘zero-COVID’ strategy, likely fuelled by the desire to have spectators present at the Beijing Olympic Games in February and the 20th National Party Congress later in the year.

Countries in the Asia Pacific are also cautiously reopening their borders. Southeast Asia is leading this effort, with Indonesian President Joko Widodo urging the creation of a regional travel corridor encompassing the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Thailand will host the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meetings in-person in 2022, while Cambodia will host the ASEAN tourism forum. The success of these endeavours, particularly for reviving tourism, will depend on the restrictions that remain in place and the ease with which travellers can enter or leave. Against this backdrop, the end-of-year wild card that could derail all reopening plans is the emergence of the new variant of concern, Omicron.

COVID-19 drives biotech boom in the Asia Pacific

Driven by supply limitations that hampered early vaccine rollouts throughout much of the Asia Pacific, COVID-19 has fuelled a biotech surge in the region. Of the eight COVID-19 vaccines the World Health Organization (WHO) has approved, four are produced in Asia. India has also announced the development of two additional vaccine candidates. Taiwan, Thailand, and Japan all have domestically-produced candidate vaccines in development that may be approved for distribution as early as 2022. Investments in building future capacity have soared throughout the region. AstraZeneca and Sanofi recently announced significant new investments in Vietnam to boost technology and production. Moderna has licensed its mRNA vaccine for production by Samsung Biologics in South Korea, and BioNTech has announced plans to build an mRNA manufacturing facility in Singapore.

Expanded vaccine and therapeutics production throughout Asia could prove hugely beneficial, both for enhanced regional distribution and initiatives such as COVAX, the WHO-backed global vaccine sharing alliance. The emergence of the Omicron variant, which likely originated in a region with low vaccination coverage, has reinforced the importance of improving global vaccine equality. There is renewed optimism that 2022 could be the year that the global community starts to address this issue more seriously.

COVID-19 boosts adoption of technological solutions to health care woes

The continued impact of the pandemic on health-care systems will be another area to watch in 2022. Pandemic fatigue has exacerbated pre-existing shortages of health-care workers, especially in Southeast Asia. Singapore is reporting a sharp rise in resignations, and the Philippines faces threats of mass resignations. Vietnam has threatened to suspend the licences of health-care workers who resign. Meanwhile, low supply and ongoing demand could give health-care workers unprecedented influence to bargain for better working conditions and pay this year.

COVID-19 has also hastened the adoption of potential solutions to these ongoing issues, including telehealth and other digital technologies, many of which had previously lagged due to regulatory hurdles and other barriers. Telehealth platform Halodoc in Indonesia saw a 101 per cent increase in active users early in 2020. MyDoc in Singapore reported a 272 per cent increase in users from 2019 to 2021. The extent to which these technologies are maintained post-pandemic will impact pandemic recovery and the future resilience of health-care systems.

But in 2022, the little-understood Omicron variant represents the largest potential game-changer for reopening plans, the biotech industry, and the health-care sector – throughout Asia and here in Canada. Omicron is suspected to be more transmissible than the Delta variant and therefore may replace Delta as the dominant variant globally. Vaccine efficacy against Omicron is currently unknown, although new vaccines could be manufactured within 100 days. Omicron’s virulence is also unknown, although some early signs indicate it may be less likely than Delta to cause severe illness. If this proves to be the case, it could tip the balance of the current debate over reopening towards an endemic ‘live-with-COVID’ approach. In this scenario, a combination of acquired immunity and milder illness could eventually render COVID-19 just another seasonal respiratory virus, similar to the cold or flu. Low mortality figures rather than case counts would be the benchmark of success. This best-case scenario could lead to New Year 2022 being what we all hoped for at the beginning of 2021.

2. Economic Recovery

According to the Asian Development Bank’s latest Asian Development Outlook supplement released earlier this month, the “recent emergence of a highly mutated virus variant and a rise in infections globally indicate that the pandemic is far from over.” Indeed, the astonishingly fast-spreading Omicron variant could dampen or decelerate global economic recovery in 2022, including in Asia. Still, the ADB’s December updates to its original September forecasts suggest that the region will continue to sustain a strong economic rebound next year. The regional gross domestic product growth forecast for 2022 is pegged at 5.3 per cent, while sub-regional growth is pegged at five per cent for East Asia, seven per cent for South Asia, 5.1 per cent for Southeast Asia, and 4.7 per cent for smaller Pacific economies.

These divergent growth trajectories – and subsequent uneven recoveries – across the region appear to be a symptom of the varying levels of success of vaccine distribution and rollout policies. Near-term risks to recovery in the emerging markets and economies will include vaccine efficacy against emergent variants of concern, lockdowns triggered by new outbreaks, supply chain disruptions, and inflation. 2022 may bring much-needed hope in accelerating equitable vaccine deployment and health-care spending.

The most vulnerable are being hit hardest

The rapid spread of the Delta variant and increased risk from the Omicron variant continue to stifle long-term inclusive economic recovery plans to address the barriers that women, youth, Indigenous peoples, and other underrepresented groups face. Already, the United Nations has estimated that the pandemic has pushed 89 million people into poverty across the Asia Pacific over the past two years. Actionable growth policies stalled due to Delta may bring a sweep of closures to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in sectors hardest hit by the pandemic. Micro, women-led businesses are on average overrepresented in industries such as tourism, food services, textiles, and apparel, which are also the hardest hit sectors by the pandemic. Meanwhile, the United Nations has also warned of the compounded effects of lockdowns on Indigenous peoples who traditionally reside in multigenerational housing and already face challenges to food security and the impact of climate change on traditional lands.

Balancing short- and long-term growth

As disruptions due to Delta and Omicron continue to impact supply chains, policy choices will remain limited to short-term measures. Disrupted supply chains will make 2022 a challenging year for inclusive growth, forcing governments to address immediate public health challenges and short-term growth over policies supporting long-term recovery plans. Recent research from the International Labour Organization suggests that the impact of job loss on tourism was four times greater than non-tourism industries, meaning that economic recovery and growth in the many economies in the region that rely heavily on this sector is more turbulent than those that are more diversified. Even where reopening is possible, the slow resumption of travel means that jobs and working hours for tourism sector workers are likely to remain low in 2022 as eager travellers weigh the risks of travel restrictions and quarantine against long-desired vacations. Thailand’s ambitious plan to reopen to over 60 countries brings some optimism for the sector in 2022, but stricter measures like the Vaccinated Travel Lanes (VTL) to and from Singapore will test the ability of policy-makers to support broader reopening strategies. If the execution of plans like Thailand’s is successful, effective short-term policies may pave the way for more robust long-term strategies in late 2022. Once short-term issues such as vaccine supply, temporary travel restrictions, and supply chain disruptions are addressed, governments will be able to turn their attention to long-term growth plans. To be successful, sustainable, and inclusive, these long-term efforts will need to support structural trade reform, investment in digital and green sectors, increased productivity and job creation, and those most impacted by the pandemic – namely, women, youth, Indigenous peoples, and MSMEs.

Finding a way forward

National plans for equitable growth and recovery are critical, considering the pandemic has challenged the survival of many businesses, particularly the MSMEs and entrepreneurs that comprise the backbone of the global economy. In November 2021, at the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) CEO Summit, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern noted that post-pandemic co-operation must involve both the public and private sectors to achieve inclusive and sustainable recovery. Elsewhere, world leaders continued to commit to and aspire towards inclusive regional frameworks such as APEC’s Putrajaya Vision 2040 to build an open, dynamic, and resilient Asia Pacific community. However, as surges of COVID-19 and the emergence of variants continue, governments will be hard-pressed to focus on long-term visions as immediate responses to COVID containment will remain the priority. Indeed, many Asia Pacific governments struggling to relaunch their economies will likely need to place long-term inclusive growth strategies on the backburner for 2022. Or at least until the equitable distribution of vaccines and other resources create conditions that permit inclusive growth that reaches everyone.

3. Labour & Migration Disruption

In year two of the pandemic, Asian employment and labour migration patterns have shifted, with significant and sometimes even counterintuitive implications. Within national borders, the ‘lying flat’ movement, originated by Chinese youth wanting to get by with as little effort as possible, has echoed across East Asia as young people become increasingly disillusioned with the ‘rat race’ of modern working life. As part of these ‘movements,’ many workers have quit their jobs to participate in the growing gig and platform economies, which offer flexibility but often come with their own controversies over working conditions. But by far, the most consequential shift throughout the Asia Pacific has been domestic reverse migration away from urban factories and back to rural hometowns, creating labour shortages of up to 25 per cent in some cities.

To some extent, these shifts have been driven by policies, some long in the making. In countries like India and China, rural modernization and a digital ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ have made earning a living in the countryside feasible and attractive. But many who have opted for the rural return have been motivated by gruelling experiences of neglect or even mistreatment by employers and urban authorities during COVID-19 outbreaks and lockdowns. Employers and governments in countries like Vietnam and Malaysia have struggled to attract local workers amidst these newfound migrant labour shortages. Businesses and governments across the region – including in Thailand, Taiwan, and Singapore – have rolled out changes to improve working conditions and incentives, but with limited success and sometimes without a willingness to tackle core grievances.

Remittances steady despite barriers to labour migration

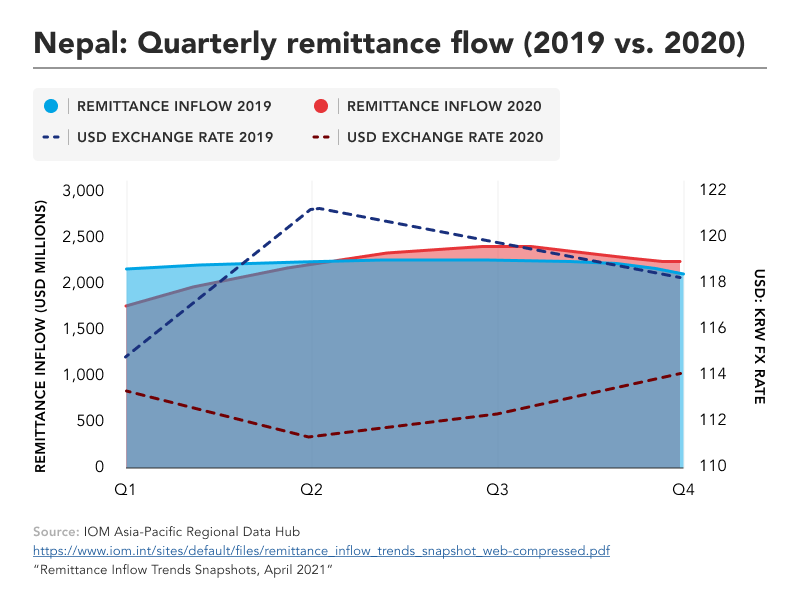

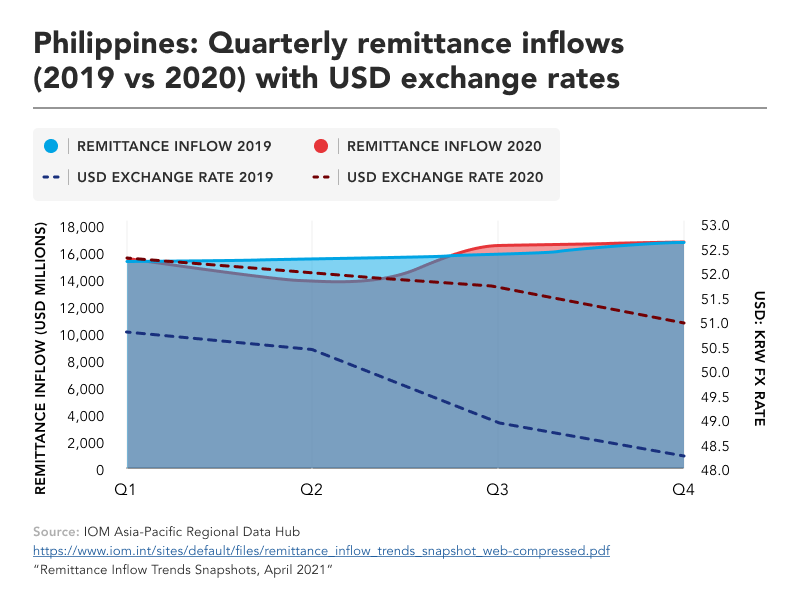

The pandemic has also had unexpected impacts on the Asia Pacific’s migrant remittance flows. Remittances are a vital source of income for migrant households and a crucial component of many countries’ economic recovery. The pandemic saw a peculiar contradiction in remittance flows in 2020. While overseas workers were severely limited by lockdown restrictions in host countries and worker repatriation measures in home countries, remittances remained either steady or rose to all-time highs in several Asia Pacific countries during the pandemic, defying earlier predictions. For example, the Philippines, well-known for its overseas labour force, only saw a 0.8 per cent decline from 2019 to 2020, with an increase in remittances in Q3 and Q4 relative to 2019. In Nepal, where remittances comprise almost one-quarter of national GDP, inflows were at an all-time high in 2020, despite the drastic reduction in the number of overseas migrant workers.

While data is not yet available for 2021, the patterns in 2020 show that even during the pandemic, migrant workers – many of whom are frontline workers – have continued to send money home to support their families by cutting their own consumption, drawing on savings, and utilizing fiscal support measures in host countries like the Canada Emergency Response Benefit. It remains to be seen whether this resiliency can be sustained in 2022 and beyond, given the pandemic’s continuing pressures on migrant workers.

A turning point for Asia’s approach to migrant workers?

Just as the pandemic demonstrated the vulnerability of international supply chains, it also highlighted the centrality of domestic and overseas migrant workers whose labour underpins national and global economies. It is not yet clear whether the impacts of COVID-19 and resulting shifts in employment and labour migration will persist, particularly given the spread of the newly identified Omicron variant. Toward the end of 2021, there have been some signs of a return to pre-pandemic labour patterns, but experts continue to predict labour shortages into early 2022.

If Asia Pacific economies continue to rely on migrant labour and remittance inflows, they will need to address the challenges faced by migrant workers over the past two years, including discrimination, job loss, financial support, and health protection. So far, governments and international organizations have been slow to address these issues or to incentivize workers to return to work, even as some open their borders to welcome new migrant workers to fill labour shortages. Some economies, such as Malaysia and Singapore, have chosen to find alternative solutions to the pandemic migrant labour shortage by investing in automation in sectors like manufacturing. Should this shift take hold, it will challenge economies like the Philippines, Nepal, Indonesia, and Bangladesh, which have relied on migrant remittances for significant portions of their GDP, and create a need to rapidly expand local opportunities re-integrate former and repatriated migrant workers. Next year will be critical in assessing whether the pandemic has indeed been a turning point for Asian labour and migration, and if governments and societies have heeded the lessons that this global disruption has wrought.

4. China's Supercharged ‘Common Prosperity’ Campaign

‘Common prosperity’ is perhaps China’s most talked-about new political buzzword. Since August, President Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have increasingly referenced the phrase in speeches and party rhetoric. According to Xi, it is a “fundamental requirement of socialism” and a mandatory step for balancing China's growth and financial stability. Xi’s ability to push this agenda as the country’s new guiding principle was solidified at the CCP’s sixth plenum in November, which marked the beginning of a ‘new era’ and confirmed Xi as the unchallenged core of Party leadership.

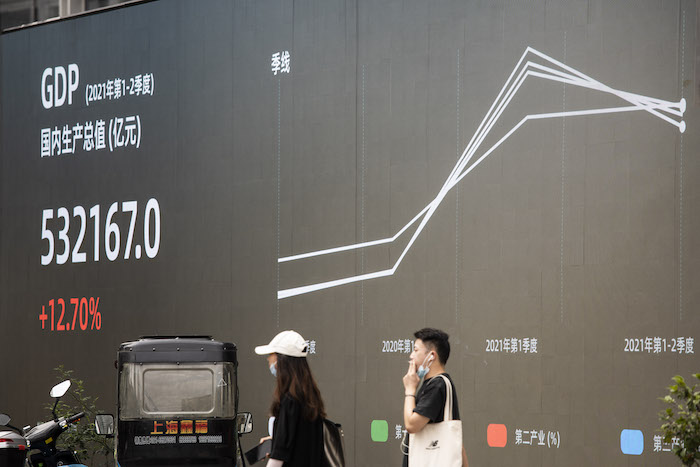

While China has boasted the world’s second-largest economy for the last decade, its income inequality has widened significantly in the past 20 years. According to 2020 national statistics, China’s richest 20 per cent earned 10 times more than the poorest 20 per cent that year. In contrast, the same measure in the United States suggests the wealthiest 20 per cent earned 8.4 times more than the poorest 20 per cent, while the same factor in much of Western Europe is closer to five. While China has the world’s second-largest share (behind the U.S.) of the top 500 wealthiest billionaires, it also has 600 million people living on an annual income of C$2,410 or less. Such economic and social gaps, which are rapidly widening, could threaten the country’s economic productivity and social cohesion. ‘Common prosperity’ is seen as a way of guiding middle-class expansion and helping shift the country's economic growth model from a labour- and manufacturing-intensive export-led model to one driven by domestic consumption.

However, ‘common prosperity’ is not a new idea; Chairman Mao Zedong first raised it in the 1950s. Still, its re-emergence signals Xi’s attempt to move away from former leader Deng Xiaoping’s governing philosophy of “let some people get rich first,” which has underpinned the country’s economic development philosophy since the 1980s.

Policy changes targeting both wealthy and poor

But ‘common prosperity’ is more than a buzzword – it is a top-down approach to organizing the next steps in China’s economic and social development. The CCP declared at its centenary celebrations earlier this year that it had attained its goal of building a “moderately prosperous society.” And last year, it declared the elimination of absolute poverty in China (although its definition of poverty as earning C$2.94 or less a day differs markedly from the World Bank’s C$7.03 poverty line for upper-middle-income countries). As a next stage, ‘common prosperity’ promises to rein in the economic growth accruing to those who have the most while helping improve the lot of the population that has the least.

The government of China has implemented various economic and social policies to redistribute income from ultra-wealthy individuals, monopolies, and major companies. Over the last year, Beijing has cracked down on some of the country’s most profitable sectors, including technology, real estate, and entertainment. Some corporate monopolies that are facing this regulatory pushback from the central government, such as on initial public offering plans, are answering Beijing’s call for “giving back to society.” Tech giant Alibaba, for instance, invested C$19.9 billion to support ‘common prosperity’ initiatives through digitalization and other development projects in rural areas, promoting local employment and creating opportunities for small businesses to grow. To tackle the nation’s real-estate bubble, the government has also raised mortgage rates in major Chinese cities while limiting the amount of debt real estate companies can hold relative to their assets. Similarly, new regulations have also been set for the entertainment industry to limit celebrities’ astronomical salaries and excessive “capitalist worship.”

To improve the lives of its poorer citizens, Beijing has begun focusing on targeted assistance programs in rural areas, such as road-building, modernization of agricultural production, and village-level e-commerce and tourism. As for addressing the economic hardship faced by the urban poor (and notably migrant workers), the government recently started setting quotas, price caps, and property taxes in some first-tier cities to address the supply of affordable housing. Furthermore, new policy measures have been taken to improve the welfare of the country’s estimated 200 million ‘gig workers,’ about one-quarter of its labour market, including unionization and wage structure reforms. Additional initiatives are expected in 2022, such as new benefit systems and social safety nets for these workers.

What the ‘common prosperity’ campaign means for China and beyond

President Xi’s push for ‘common prosperity’ comes with various overarching, long-term goals and milestones for 2035 and 2050. But lacking a detailed blueprint, it remains uncertain what will come in 2022. Observers are doubtful whether China’s ruling elites will support the campaign. They see the potential for a backlash if the change is too dramatic. In fact, tax reforms affecting the wealthy have stalled due to resistance.

In 2022, we will likely see measures to address concerns around massive wealth redistribution and others to enhance the business environment and help with sustainable business growth. Meanwhile, the ‘common prosperity’ campaign could put the central government in a bind if its actions run contrary to this new guiding principle. For example, when ‘systemic challenges’ like the Evergrande liquidity crisis emerge, they raise questions about whether the government can justify rescuing severely indebted developers. Beijing’s more inward-looking, inequality-focused approach in managing its economy, together with the flurry of further policy changes and tightening of regulations expected in 2022, could also have the unintended consequence of impeding domestic entrepreneurship and innovation. And it could add a new layer of complexity to an already strained business environment for international companies operating in China.

5. The Mega Free Trade Deals

After years of discussion, the long-awaited Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest free trade agreement (FTA), will enter into force on January 1, 2022, for the 11 countries that have ratified it. The RCEP signatories make up 28 per cent of global GDP and 30 per cent of the world’s population. It is the first FTA to include China, Japan, and South Korea – three of the four largest Asia Pacific economies. RCEP required ratification by at least six ASEAN and three non-ASEAN signatories to enter into force, a requirement that was met on November 2. The agreement has now been ratified by Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Japan, Laos, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam. Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and the Philippines are the other signatories yet to ratify.

What’s the big deal?

RCEP’s size is not its only notable feature. The fact that China is the pact’s largest economy and Beijing heavily promoted the deal underscores a driving narrative behind the agreement: Even though it is a triumph of ASEAN leadership, at its core, it is a China-centric deal. China’s centrality in the agreement has generated debate about the FTA’s potential for further increasing China’s importance as a trade partner for signatories and its potential for further integrating regional supply chains with China. Observers have also pointed to the agreement being finalized during the COVID-19 pandemic as an indicator of its importance to the signatories as a driver of post-pandemic economic recovery.

As the second-largest economy in the world, China is already a critical regional trade partner for Asia Pacific economies, and RCEP will only increase its importance. Consider China’s trade relationship with Japan; in January 2021, China purchased more than 20 per cent of Japan’s exports, surpassing the United States as Japan’s largest trading partner. Since 2020, Japan has also been the third-largest destination for Chinese exports, following the United States and Hong Kong. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this trade relationship is that it developed in the absence of any FTA between the two economies. Now that RCEP will reduce barriers to the flow of goods, trade between Japan and China is only expected to deepen.

One of RCEP’s biggest coups is its unification of the ‘rules of origin’ amongst member countries, which will allow for more streamlined supply chain integration. This aspect of the deal is expected to result in some supply chain reshuffling as goods sourced among RCEP members will benefit from preferential tariffs. In contrast, goods sourced elsewhere will be more costly to import and export. Some analysts also note that the pandemic will likely encourage economies to pursue shorter supply chains, which will ensure China’s continued supply chain centrality in the Asia Pacific.

During the pandemic, many economies discussed or imposed protectionist policies. However, RCEP was signed and ratified during COVID-19, which indicates the strong commitment of these countries to economic growth through globalization. The Asian Development Bank has argued that RCEP will boost post-pandemic recovery for signatories, and “[b]y 2030 . . . increase members’ incomes by 0.6 per cent.” The signing of this FTA is even more significant in the context of the historical, political, and economic tensions that persist between and among members. The newly minted Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership demonstrates the region’s ability to co-operate on an economic front despite numerous challenges and the prioritization of economic prosperity over political tensions.

RCEP vs. CPTPP

RCEP is often juxtaposed with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which accounts for about 13 per cent of global GDP and is the Asia Pacific’s second-largest FTA. While there is some overlap in membership and the FTAs share some goals, such as reducing tariffs and promoting market liberalization, they are also regarded as representing different approaches to trade.

RCEP aims to reduce 90 per cent of a wide range of import tariffs between member states within 20 years and standardize some rules for e-commerce, investment, trade, and intellectual property. Much of the deal is about simplifying the complexities of existing agreements among RCEP members, including the aforementioned rules of origin. While RCEP covers much ground and is sometimes seen as an alternative to the CPTPP, it is also considered a low-ambition and old-school agreement as it focuses on tariffs rather than more progressive, next-generation elements.

Conversely, the CPTPP has a more ambitious and progressive regulation agenda than RCEP on labour, the environment, intellectual property, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, and it has a more robust dispute settlement mechanism. It aims to reduce 99 per cent of tariffs on imports among its members, a significantly higher goal than RCEP. The CPTPP also allows for broader market access than RCEP by allowing members to only protect certain strategic domestic industries.

What to Expect in 2022

In 2022, RCEP will shift from negotiation to implementation, and we can expect ratification issues and anti-RCEP issues to arise in several countries. In the Philippines, domestic opposition has been growing, notably from farmers’ groups who feel foreign agricultural products will threaten their livelihoods. But despite domestic opposition in some countries, all remaining RCEP signatories, except Myanmar, will likely ratify the agreement before the end of 2021 or early in 2022.

Next year will also see debates around the expansion of the CPTPP, particularly the competing applications of China and Taiwan to join the agreement. Taiwan’s application puts tension on all signatories’ relationships with China over Taiwan’s candidacy. Canada is obligated by the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) to obtain approval from the U.S. and Mexico if entering a free trade agreement with a non-market economy such as China. This roadblock faced by Canada (and Mexico), in addition to much analysis suggesting that China would not meet the criteria for the CPTPP’s more progressive requirements, certainly render its application unlikely to succeed. On the face of it, Taiwan’s CPTPP application will be more likely to meet the pact's criteria on progressive trade issues. But its application will be accompanied by staunch opposition from China around Taiwan’s inclusion being tantamount to political recognition, despite Taiwan using the name “the Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu” in its application.

6. The Accountability of Big Tech

Facebook made headlines in October for all the wrong reasons when its family of applications – Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram – went down for approximately six hours. Facebook, now under the recently-formed parent company Meta, later attributed the outage to a catastrophically faulty router update. While the outage frustrated many users in North America and Europe, it caused significant disruptions across South and Southeast Asia for millions of people. In economies like India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, businesses of all sizes depend on Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram as e-commerce platforms to run advertising, products sales, and customer communications.

Most users across these economies were quick to jump on alternatives like Telegram, a privacy-conscious mobile app similar to WhatsApp. However, the outage highlighted the overreliance on foreign-developed applications in Asia, particularly in developing countries. Countries with their own social network and messenger alternatives like China, South Korea, and Japan – all with widely used multifunction applications like WeChat, Naver, and Line – were impacted much less or not at all.

Fanning the flames of social discord

The outage came when Meta (formerly Facebook) was already mired in scandal after a whistleblower leaked internal research and documents confirming the tech giant’s failure to curb hate speech, violence, and misinformation across its apps. The impact of these failings has been deeply felt in India and Myanmar, home to well over 300 million Meta-product users.

Although the company has prioritized India and Myanmar for harm-reduction efforts, the bulk of its budget for such measures remains earmarked for classifying harmful content and misinformation in the United States (87%), leaving a paltry budget (13%) for the rest of the world. While Facebook argues it has made significant progress moderating content in Hindi and Bengali – which only represent one-tenth of India’s constitutionally recognized languages – its machine learning systems trained to take down abusive or fake news posts have struggled to recognize a fraction of the millions of multilingual posts propagated on Indian feeds.

The prevalence of toxic content in India has also been exacerbated by Facebook’s recommendation algorithm, which barrages users with ‘popular’ (read: controversial) content such as unverified news about tensions with Pakistan and the ongoing conflict in Kashmir, Hindu-nationalist hate speech, and anti-Muslim propaganda. Independent investigations by Indian researchers and journalists also confirm the company’s failure to take down inflammatory and abusive content from groups linked with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party for fear of repercussions to its business operations in India.

Similarly, internal documents confirm hate speech and misinformation continue to thrive on Facebook in Myanmar. In 2017, hate speech and posts inciting violence on Facebook exacerbated human rights abuses by the military junta and civilian extremists against the Rohingya. Facebook admitted in 2018 that it had not done enough to remove harmful and violent posts, vowing to improve its content oversight for Myanmar. However, the leaked internal documents show how Facebook content accessible through VPNs in Myanmar still incites violence against groups opposing the military junta, and that automated content classifiers and misinformation detection systems have been left in disrepair.

Prospects for regulation

In 2022, foreign internet platforms will continue to face intense criticism for their continued contributions to toxic and polarizing digital spheres in Asia. As a key player with little to no competition in South and Southeast Asian markets, Meta will remain torn between securing its business interests in the region and rehabilitating its tarnished reputation. Much of the company’s woes with hate speech and misinformation stem from its algorithms designed to maximize user engagement across its apps. Inflammatory content lures users to keep scrolling and draws strong responses, successfully fulfilling user-engagement tenets at the expense of social cohesion. Solutions like local-language moderation will be a sluggish, uphill battle unless platforms make long-term and consequential investments in linguistically-relevant moderation mechanisms, both in human and machine form.

Also in the coming year, global technology companies will likely face regulatory and legal pressures, making them more accountable for their real-world impacts. For instance, a parliamentary panel in India has recommended that social media platforms be governed similarly to publishers through a specialized oversight body. U.S. and U.K. lawyers representing Rohingya refugees have also sued Facebook, seeking reparations for the platform’s role in fuelling the community’s violent persecution. While regulation may contribute to making tech companies more accountable, it remains to be seen if it will translate into changes to user-engagement algorithms, or reduce online hate speech, misinformation, and incitement of violence on these platforms.

7. The Rise in Militarization

Militarization in parts of Asia has been a growing trend for years, but 2021 saw a notable acceleration in East Asia with the renewal of the U.S. ‘pivot’ under the Biden administration and an increasing military buildup by various regional players. The ‘pivot to Asia’ was crafted by the Obama administration and announced in 2011 as a plan for the U.S. to boost its presence and engagement within the region. With its withdrawal from Afghanistan completed in August, the Indo-Pacific has finally become the region of focus for the U.S., militarily and strategically, with a particular emphasis on East Asia.

Various countries, including France, the U.K., and Germany, have also stepped up their military activities in the region. Even Canadian navy ships transited through the area in 2021 while participating in training and monitoring missions. Regional players have also been active. Japan, for example, has been stepping up its Self-Defense Forces and is set to double its military spending in the coming years. Taiwan is also prioritizing the modernization of its armed forces and is augmenting its defence budget accordingly. In October, various sources reported that a U.S. special operations unit and a contingent of Marines have been training Taiwanese military forces on the island for at least a year.

Meanwhile, China has been advancing its plan to turn the People’s Liberation Army into a ‘modern fighting force’ able to compete with the U.S. in the Western Pacific by the 100th anniversary of its founding in 2027. It now possesses far greater military resources to advance its interests and project its power throughout the region. In addition to boasting the world’s largest army and navy in terms of the number of soldiers and battleships, China has also demonstrated significant technological progress. For example, its newest aircraft carrier, which could launch in the first quarter of 2022, is believed to be as technologically advanced as anything in the U.S. fleet. It has also enhanced its defensive missile capabilities. China’s two hypersonic missile tests conducted earlier this year show it is developing advanced weaponry that is outpacing some U.S. military tech. And this year’s U.S. Department of Defense annual report on China’s military power estimates that China has been significantly expanding its nuclear forces.

‘Western’ multilateral efforts in East Asia have also expanded. This year, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad), a diplomatic alliance between the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia, gathered momentum. The four leaders held their first leader-level meeting in March and their second in September. Their September Joint Statement reaffirmed the Quad’s commitment to promoting a “free, open, rules-based order, rooted in international law and undaunted by coercion” in an Indo-Pacific that is vital to the bloc’s mutual security and prosperity. September also saw the launch of AUKUS, a new security pact, enabling the U.S., U.K., and Australia to deepen information and technology sharing and increase co-operation in several security areas, including the adoption of a nuclear submarine capability in Australia.

Could a heightened US-China rivalry lead to confrontation?

This intensely militarized situation speaks to the insecurity felt by countries worldwide regarding China’s dramatic rise. It also highlights the unease created by the ‘America first’ policy initiated under former US President Donald Trump, leading governments of all stripes to reflect on their own security and beef up their defensive capacities. While the Biden administration’s international focus in its first year was on rebuilding ties with allies, insecurity regarding the future behaviour of the U.S. towards its allies and globally persists.

While the U.S. remains the world’s dominant military power, China’s increased military and deterrence capabilities could bolster Beijing’s confidence and lead it to take heightened risks. In the wake of its crackdown on Hong Kong, China has already significantly escalated its pressure on and intimidation of Taiwan this year by sending a record number of planes into Taiwan’s Air Defense Identification Zone and upping its war rhetoric toward the island. The Taiwan issue could spark an unwanted crisis, even a military conflict.

Some Western analysts argue about the inevitability of a conflict between the U.S. and China and press for countries to balance China’s rising might as the only way of preventing armed conflict. Others worry about the risks of the regional military buildup potentially leading to a ‘security dilemma’ – wherein countries view their security in zero-sum terms, namely that any increase in an adversary’s military capability requires a countervailing buildup – that could bring war closer. While the further deterioration of China-U.S. relations is in no one’s best interest, neither is the risk of a confrontation, accidental or otherwise. The virtual meeting between U.S. President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping on November 15 was a welcome step toward stabilizing the U.S.-China relationship, but next year will be pivotal for both superpowers to develop a framework to guide their increasingly competitive and unstable relationship. While many different outcomes are possible, we hope Chinese and American diplomats translate the incipient goodwill some saw in the Xi-Biden summit into genuine de-escalation efforts.

8. The Possible Collapse of Myanmar

Almost a year after the February 1st coup that toppled the democratically-elected National League of Democracy (NLD) government led by Aung San Suu Kyi, the situation in Myanmar continues to deteriorate.

Citing voter irregularities, the junta cancelled the results of the November 2020 polls despite international and local observer groups deeming them free and fair. Suu Kyi faces a raft of criminal charges, including incitement against the military, which could see her jailed for life.

Rapid currency depreciation, skyrocketing food and fuel prices, and an acute cash shortage have plunged the people of Myanmar into economic despair. A recent survey by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) confirmed its earlier projections that by early 2022 nearly half of Myanmar’s population will be living below the national poverty line. Urban poverty will triple due to the ongoing pandemic and political crisis. Rising poverty rates will significantly hamper Myanmar’s overall economic development.

An Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)-led diplomatic effort, which had initially shown some promise, failed to produce any breakthrough. Coup leader Min Aung Hlaing has not implemented any of the bloc’s five-point consensus, which includes the immediate cessation of violence, the appointment of an ASEAN envoy to facilitate dialogue, and the delivery of humanitarian assistance. Instead, violence has only intensified.

In response to the military’s increasingly brutal repression of its opponents, the National Unity Government (NUG), a parallel government composed of ousted lawmakers, has declared a “people’s defensive war” calling for nationwide armed resistance against the military regime. Civilian militias have joined forces with several ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) and launched guerrilla-style attacks on the Myanmar military, or tatmadaw, across the country.

Since the coup, some 1,300 civilians have been killed by the military, more than 200,000 people have been displaced, and about three million are in urgent need of humanitarian aid.

A dangerous impasse

Both the military regime and resistance forces are determined to prevail, but neither has dealt a decisive blow. Neither side has shown interest in a negotiated settlement despite calls from foreign officials and observers for a peaceful resolution.

A significant challenge for the parallel NUG is rallying more anti-junta EAOs, some of which wish to maintain their autonomy and are mistrustful of the NUG due to past difficulties with the NLD government. However, even if the NUG manages to unite all groups, tatmadaw is still much larger and better equipped than civilian and ethnic militias. The tatmadaw has deployed heavily armed combat battalions to suppress dissent, used airstrikes in rural areas, and restricted access to food and aid to weaken insurgent groups. The United Nations-affiliated investigative body announced last month that it has collected preliminary evidence indicating that systemic attacks against civilians by the military amount to crimes against humanity.

And yet, the military, with all its power, has not been able to overcome the resistance forces. Opposition to the junta remains widespread and has only strengthened in the wake of increased military violence. Resistance fighters have inflicted significant damage on military convoys and critical infrastructure, and morale appears to be declining inside the tatmadaw as a greater number of defections are being reported. While the future is uncertain, Myanmar is on a trajectory of prolonged civil conflict.

Finding a way forward in 2022

There is little doubt that the military government will try to extend its hold on power. Although leader Min Aung Hlaing stated that fresh elections will be held in August 2023, these are unlikely to be free and fair.

Since the coup, the junta has been able to stay afloat despite targeted sanctions imposed by Western governments on military-controlled conglomerates. While revenues from the illegal drug trade and jade primarily sold to China through proxy companies have allowed the junta to survive so far, this could change if its coffers continue to diminish. The NUG, meanwhile, has reportedly raised US$700 million through fundraising efforts and is supporting humanitarian relief and COVID-19 vaccinations for people and striking workers in Myanmar. These efforts may help provide temporary relief for citizens, but the economy could collapse if the recession and persistent inflation are not addressed.

The United Nations and several countries, including Canada and the United States, have raised concerns over recent reports of ongoing human rights violations and abuses by the military, particularly in the country’s northwestern regions. However, diplomatic efforts to address the ongoing crisis have largely been left to ASEAN, which appears hamstrung due to disagreements on how assertive it should be toward Myanmar’s military government. ASEAN’s refusal to include Min Aung Hlaing at its summit in October was an important challenge to the regime’s legitimacy. But consensus-building may become harder with Cambodia as the new ASEAN Chair, given the country’s closeness to Beijing. In the past, Cambodia has often sided with China and obstructed initiatives from the regional bloc. Given that both countries have refrained from openly criticizing Myanmar’s military regime, and that earlier this month, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen met with the junta-appointed foreign minister in Phnom Penh, it is unlikely that ASEAN will push for a tougher stance toward Myanmar in 2022.

While the hope is that military rule in Myanmar will come to an end, this may not immediately bring peace to the country. More work needs to be done to build trust and engagement amongst diverse domestic groups on the structure of a future federal union. Until then, the spectre of the military dictatorship that ruled the country from 1962 to 2011 looms large and threatens to undo much of the progress achieved so far by millions of people who have dedicated their lives to Myanmar’s democratic future.

9. The Afghanistan Problem

The collapse of Afghanistan’s elected government was one of 2021’s most cataclysmic events. Some initial assessments suggested that the U.S. withdrawal could benefit China by creating breathing space to expand its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, Beijing’s overriding concern vis-à-vis Afghanistan is not investment or infrastructure, but security. Specifically, it wants assurances from the new government in Kabul that terrorist groups will not use Afghan territory to plan and carry out attacks against China. The Chinese government made these demands clear when it hosted the Taliban for a high-level meeting in July, about one month before the latter re-took power.

The Taliban, desperate for China’s help in rescuing an economy in free fall, has been happy to oblige. In September, Beijing pledged C$40 million in assistance, including food and COVID-19 vaccines. Just weeks later, the Taliban re-located Uyghur extremists away from its eastern border with China’s Xinjiang region. What is less clear, however, is whether the Taliban would be willing and able to help neutralize another terrorist group of concern to China: Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), also known as the Pakistani Taliban. In the confounding tangle of regional alliances, the Afghan Taliban is allied with both the TTP and the government of Pakistan, whereas the latter two are sworn enemies. Although the TTP has been degraded by internal divisions and years of U.S. and Pakistani military bombings, the Afghan Taliban’s resurgence has had a galvanizing effect. Since August, the TTP has carried out more than 70 attacks in Pakistan, including some against Chinese interests in that country.

A crack in the iron brotherhood

China and Pakistan describe their relationship as one between “iron brothers.” The clearest manifestation of this relationship is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship BRI project valued at nearly C$80 billion. When it was launched in 2015, Pakistan hoped that the CPEC would help transform its impoverished and politically volatile western region. Now, it is not only grappling with serious cost overruns, but the project – and China’s presence in Pakistan, in general – is on the TTP’s hit list. For example, in April, a Chinese diplomat in western Pakistan was the presumed target of an assassination attempt that left five people dead, and in July, nine Chinese engineers working on a hydropower project in the southwest were among 13 killed in an attack on a vehicle convoy.

In the latter case, Islamabad initially downplayed the possibility that the fatalities were due to terrorism. But Beijing pushed back, pressing Pakistan to rein in the threat and demanding C$48.5 million in compensation for the Chinese lives lost. The demand is being discussed in Islamabad, but has reportedly been described by some in the Pakistan government as “irrational.”

Negotiating, but from weakness?

In late 2021, there were tentative signs of progress in reducing the TTP threat. On November 9, Islamabad and the TTP began a one-month ceasefire, with the Taliban facilitating the talks. Some observers are skeptical; the Afghan Taliban recently released nearly 800 TTP members from Afghan prisons, and Islamabad’s negotiating position was constrained by public pressure not to offer amnesty to members of a group that has killed tens of thousands of Pakistanis – both security forces and civilians, including many children.

Unfortunately, the skeptics did not have to wait long to be proven correct. On December 9, the TTP unilaterally withdrew from the ceasefire, despite initial hopes that it would be extended. Its spokesperson cited the Pakistani government reneging on a pledge to release about 100 foot soldiers, and charged it with carrying out raids and arresting additional TTP fighters. The news will no doubt alarm both Pakistan and its “iron brother,” China. In addition to a possible resumption of TTP-initiated violence, the end of the ceasefire may also reflect the limits of the Taliban government’s ability to contain another ascendant threat, the Islamic State-Khorasan (IS-K). IS-K, based in eastern Afghanistan, is responsible for some of the deadliest bombings in Afghanistan in recent months. It has also recruited some disaffected Uyghur militants into its ranks. That, many experts believe, has very likely raised anxiety levels even further in Beijing.

China and Pakistan’s ability to work with Afghanistan to lessen the threat of terrorism in the coming year depends a lot on how effectively they can leverage their relationship with the Taliban. However, almost immediately after taking power, the Taliban began splintering into rival power centres, some sympathetic to the types of bad actors that will act as spoilers in any attempt at peace. At the moment, all signs point to another deadly and tumultuous year in Afghanistan. Whether its new government can limit the fallout for its neighbours will be a test of its relationship with two vitally important diplomatic partners.

10. The Clean Energy Transition

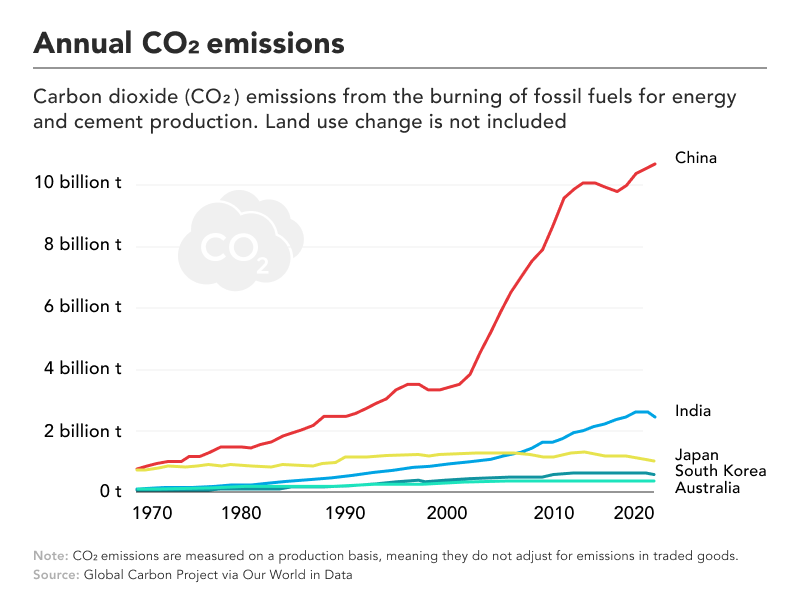

From droughts and fires in Australia, changing monsoon patterns in South Asia, and severe flooding in China to the heat dome, fires, and floods in Western Canada, catastrophic effects of climate change were front-and-centre throughout 2021. A landmark International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report published in August provided the clearest scientific evidence to date linking carbon emissions from the burning of fossil fuels to climate change. It stated that we are at a “code red for humanity” and that drastic and urgent action to curb carbon pollution is urgently required. The IPCC report added a layer of anticipation for the COP26 climate conference held in Scotland in October and November, which was already set to be the most significant climate meeting since COP21 in Paris in 2015.

At the conference, officials announced their latest nationally determined contributions (NDCs) for reducing carbon emissions, and agreements were negotiated to end deforestation and reduce the global output of the greenhouse gas methane by 30 per cent, both by the year 2030. But the summit’s final communiqué attracted broad criticism as it committed to the “phase down” of coal as a source of electricity instead of its “phase out.” The last-minute change in language came about as India, with support from China and other coal-reliant developing countries, threatened not to sign the final document unless the coal provision was weakened.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced that his country’s carbon-intensive economy would transition to carbon neutrality by 2050, although with precious few details on how that would be achieved. Chinese representatives expanded modestly on prior pledges to reach peak carbon emissions by 2030, achieve net-zero emissions by 2060, and end financing for coal-fired power plants outside China. Climate co-operation between Chinese President Xi Jinping and U.S. President Joe Biden failed to materialize at a virtual bilateral summit following COP26. The two leaders discussed the global threat posed by climate change, but they were unable to agree on areas of co-operation. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi indicated his country would achieve carbon net-zero by 2070, with half of its power coming from renewables by 2030, a pledge seen as a disappointment by many international climate observers. Many Indian analysts, however, applauded it as an aggressive yet realistic target that acknowledged the country’s attempts to lift millions out of poverty in the coming years.

Contesting COP26 internationally and in the Asia Pacific

International media outlets reported hostility toward the summit from civil society groups and others. Climate activists who took issue with the summit’s goals and the pace of action organized large protests outside the event. Roughly 100,000 people participated in a rally that featured firebrand climate activist Greta Thunberg. Leaders of small Pacific Island states already experiencing the most rapid and severe consequences of climate change also demanded more action. Tuvalu’s foreign minister, for example, caused a stir by addressing COP26 knee-deep in seawater while wearing a suit and tie, highlighting the impact of sea-level rise on his country. Hundreds of civil society observers walked out of the event in protest on its last day after being shut out of areas where negotiations took place. COP26 president Alok Sharma offered a tearful apology, seeming to acknowledge that the summit did not accomplish many of its lofty goals.

What to expect in 2022

Achieving carbon reductions requires countries to move beyond pledges to action to contain and reduce emissions, and many observers feel major emitters in the Asia Pacific aren’t doing enough in the short term to achieve deep emissions cuts. In the months before COP26, for example, India increased the amount of coal it was burning in power plants as electricity demand grew. China also expanded its coal production after announcing plans to build more than 40 coal-fired power plants in the coming years. China, India, Indonesia, Japan, and Vietnam are responsible for 80 per cent of the new coal-fired power plants currently planned globally.

With presidents Xi and Biden unable to find common ground for climate co-operation, we are looking to climate financing in 2022 as a significant driver for reducing emissions in the region. China’s declaration that it will no longer finance coal power plants outside China is a big deal. A recent analysis estimates the move will lead to a reduction from 65 gigawatts (GW) of coal plants being constructed in Asia (outside China and India) to just 22 GW, or a decrease greater than Ontario’s total electricity generation capacity. The move scuppers construction on nearly all of the planned coal plants in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and about two-thirds of the coal plants scheduled for construction in Indonesia, among others.

These countries and others in Asia will need to replace that generating capacity with other forms, and effective financing could see the lion’s share coming from renewables. But who will front the money? A pledge made by developed countries in 2009 to contribute US$100 billion per year by 2020 to help finance renewable energy in developing countries fell far short of its mark. Even so, a renewed pledge championed by the foreign ministers of Canada and Germany this year aimed to hit that goal by 2023 and to exceed it thereafter.

COP27, scheduled for November 2022 in Egypt, will be an opportunity to take stock of action taken in 2021 made in pursuit of promises by leading polluters in the Asia Pacific.

Time Capsule

APF Canada's Earlier Year-End Dispatches:

Go back in time with APF Canada's prognosticators and read our other year-end reviews: