The distribution of COVID-19 vaccines is picking up pace in low- and middle-income countries in Asia, raising hopes that government restrictions on mobility and mandatory quarantines will be loosened in the coming months. Nonetheless, the increasing availability of vaccines does nothing to address a problem that bedevils many countries, and not only in Asia: the lack of vaccine enthusiasm, the reluctance, in other words, by a large share of the population, to get vaccinated. This phenomenon could give COVID-19 variants the opportunity to evolve, spread, and significantly slow the pace of economic recovery.

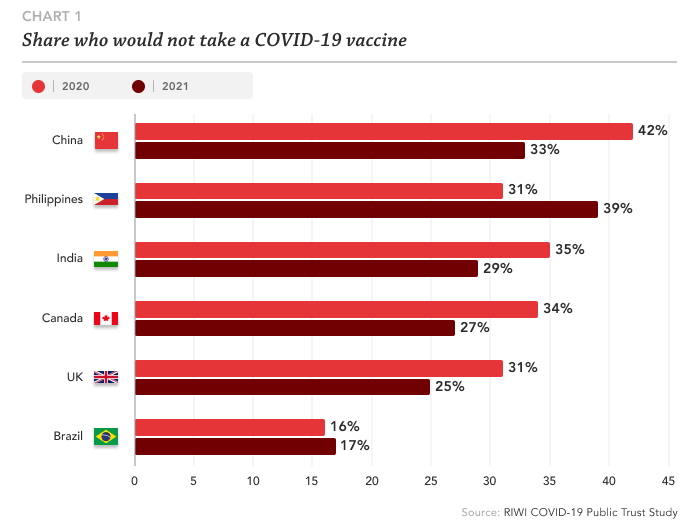

The Philippines, India, Malaysia, and Indonesia now rank at the bottom of Bloomberg’s COVID resilience ranking. Data collected by RIWI, a Toronto-based company that offers tracking surveys and predictive analytics, show that about 40 per cent of respondents in the Philippines and about one-third of respondents in China and India say they will not take a COVID-19 vaccine (see Chart 1) [1].

RIWI uses a method that allows random exposure for anyone with online access in any country. As a result, these data, collected continuously every day between March 2020 and June 2021, reflect broad-based sentiment. The data include opinions of individuals who do not habitually respond to polls or participate in surveys, nor are they individuals likely to use social media to express their views on vaccination. Unlike other surveys, RIWI does not collect personal identifiers; guaranteed anonymity maximizes honest answers.

While vaccine confidence is a major challenge and remains insufficiently high across almost all countries, it has been rising in Western countries like Canada and the United Kingdom as vaccine rollout ramps up. Whereas willingness to “get the jab” has been consistently high in pandemic-ravaged Brazil, confidence declined abruptly in the Philippines over most of the first half of 2021.

Last year, RIWI data showed that 31 per cent of respondents in the Philippines were unwilling to take a COVID-19 vaccine. But in January 2021 it peaked at 50 per cent unwilling and averaged 43 per cent between February and May of 2021 (it started to decline a bit later in May and into June). In China, 42 per cent were unwilling to take a COVID-19 vaccine last year. While this has improved, 33 per cent of Chinese respondents still do not plan to get vaccinated as of June 2021. In India, despite its deadly outbreak, the latest data show that 29 per cent do not plan to get vaccinated. RIWI findings across countries generally point to lower vaccine confidence than typical official surveys or panel-based surveys that are not random or anonymous.

Aggressive actions taken by the Chinese and Philippine governments suggest recognition that the lack of confidence in vaccines has become a major health and economic problem. While China has administered a remarkable one billion vaccine doses, this is only about half the number required to achieve herd immunity, a goal that the country’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention hopes to reach by mid-2022.

A series of health-related scandals in China in recent years has made many people suspicious of the large-scale vaccination campaign, particularly as word spread about COVID cases surging in countries that have been reliant on vaccines made by the Chinese pharmaceutical firms Sinopharm and Sinovac Biotech. In China, supply is not a problem, but demand from the population remains lukewarm. The vaccination campaign is also a paradoxical victim of the country’s relative success in containing the virus via masking, distancing, testing, tracking, and border closures and, as a consequence, life returning more or less to pre-pandemic normality.

But outbreaks of the Delta variant of COVID-19, such as the one witnessed in the southern province of Guangzhou in early June, are a reminder that continued vigilance is required. With this in mind, central government authorities recently announced that China’s border restrictions will be kept in force for another year.

To keep up the pace of vaccinations, China is using the tools and tentacles of the powerful state bureaucracy. Where persuasion and incentives like shopping vouchers don’t work, mandates and strong-arm measures are put in place. Official documents demanding that employees of government bodies be vaccinated have surfaced on Chinese social media platforms such as Weibo, including documents issued by the Shandong Province city of Yantai and Fujian Province’s Anxi County. In some instances, housing compounds have banned residents from returning if they are not vaccinated. Universities have linked immunization numbers to teacher performance and student grade assessments. The municipal government of Wanning, in Hainan province, reportedly warned residents who refused vaccination that they could be prevented from receiving government benefits or using public transport.

The Philippines has had great difficulty securing doses for its 111 million people, but the country has just signed its biggest vaccine supply deal to date, an agreement for 40 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine developed by Pfizer and BioNTech. Confidence in taking those vaccines was already low in 2020, in part due to a debacle surrounding an earlier dengue fever vaccine. Confidence dropped further in early 2021.

This tepid take-up of vaccine doses led the country’s president, Rodrigo Duterte, to threaten people with jail or an injection of an anti-parasite drug widely used to treat animals if they refused to be vaccinated. Unsurprisingly, RIWI’s measure of intentions to get a vaccine shows a large drop in those who say they will not get vaccinated since the president made his threat on June 21.

Before President Duterte issued his warning, 39 per cent of respondents between March 1 and June 21 said they would not take a vaccine. After his threat (June 22-July 6), only 23 per cent of respondents reported they would not take a vaccine. It is possible that other factors also influenced the changing attitude among the Philippine population, such as people witnessing friends and family getting vaccinated and suffering no serious side effects.

Although vaccine hesitancy is less pronounced in India, it warrants great concern in a country ranking third globally in COVID-19 deaths, where, as of now, less than five per cent of the population is fully immunized. Vaccine refusal has been fuelled by misinformation and mistrust, particularly in rural areas. False claims about adverse reactions are circulating widely, exemplified by the rumour that vaccines lead to impotence and even death, while some believe that they are simply immune to COVID-19.

In Indonesia, which is currently experiencing a new surge in COVID-19 cases and has southeast Asia’s worst outbreak with more than two million cases, religious micro-influencers (those with between 10,000 and 50,000 followers on TikTok) are spreading anti-vaccine messages rife with conspiracy theories, anti-government narrative, and anti-Chinese sentiment.

As developing Asian countries secure doses to vaccinate their populations, the race is on to convince sufficient numbers of citizens to use them and achieve herd immunity ahead of the spread of variants. Or governments will be forced to renew lockdowns and other restrictions that could prove devastating for morale and economic progress by stopping social interaction and halting commerce. Continued efforts are required in these countries to bolster public trust in vaccines and “persuade the persuadables.”

Trust in public health measures such as vaccination is critical for the next phases of the COVID crisis, especially since COVID-19 may well become an endemic virus. Public authorities need to invest effort and resources into nurturing trust rather than taking heavy-handed approaches. Consistency among officials in their messaging and transparency around new knowledge as it emerges is essential. It is important that trusted figures outside of government (religious leaders, popular sports and entertainment stars, and well-spoken scientists) be enlisted to publicly highlight the link between vaccination and a return to familiar activities. Otherwise, the pain of the pandemic will continue, lives will be lost, and full economic recovery will not be achieved.

Endnote:

[1] Data are from selected countries in the RIWI COVID-19 Public Trust Study which has been running on a continuous basis since March 2020. Data in this chart are from March-December 2020 and from June 2021, except in India (April-June 2021) and the Philippines (March-June 2021) in order to report on over 1000 respondents in each of those countries. In the Philippines the share refers to data pre-June 21, 2021 when the President threatened to jail people if they did not get vaccinated. Respondents are aged 14+, unique, anonymous, non-incentivized, and randomly engaged from the online population, then weighted to population demographics. Respondents in Brazil (20,873 in 2020 and 9,615 in 2021), Canada (18,224; 1,879), China (21,838; 3,662), India (3,410; 1,032), Philippines (3,196; 1,054), UK (22,017; 4,115). Respondents answered, “If a COVID-19 vaccine were available and mandatory by law, would you: take the vaccine; not take the vaccine.”