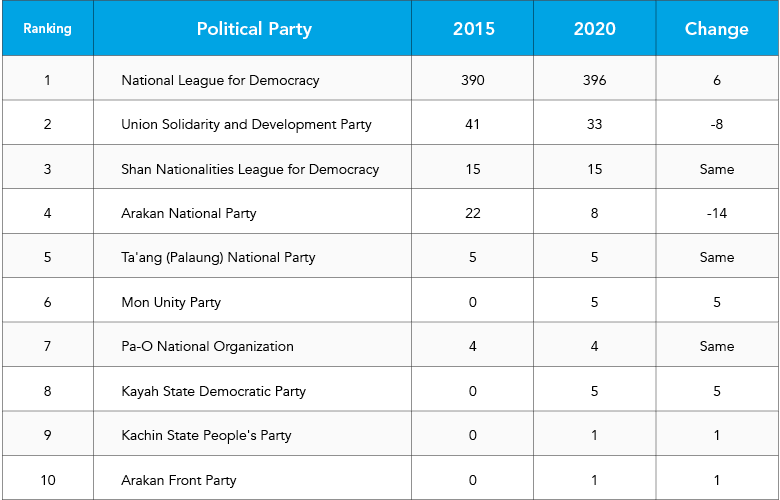

On November 8, Myanmar held its second election since the end of military rule a decade ago. The country joined a handful of others that have successfully held elections amid the COVID-19 pandemic. On November 14, the Union Election Commission (UEC), Myanmar’s electoral body, announced that the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD), led by State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, claimed 396 seats out of a total of 476 seats in a landslide victory that surpassed their 2015 win. The largest opposition party, the military-affiliated Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), ceded most of its stronghold seats in military towns to the NLD. Local ethnic parties managed to cut into the NLD’s winnings in ethnic regions such as Rakhine, Shan, and Mon states, but performed below expectations overall, despite forming mergers and alliances to boost their chances.

In its second term, the NLD will face the formidable task of bringing different groups with competing interests to the same table to resolve decades-old conflicts. Backed by another popular mandate, how will the NLD traverse the next five years? In this Election Watch dispatch, we discuss the main takeaways from the 2020 election and the challenges facing the newly elected government as it forges new relationships and strengthens others.

The NLD remains popular, and fears of military rule linger

Analysts inside and outside the country have criticized Aung Sang Suu Kyi for failing to make significant progress on constitutional reform and the peace process, two key promises in her 2015 campaign. More worryingly, under the NLD’s rule, there has been an increase in the jailing of journalists and activists, and an intensification of conflict between the Burmese military, or Tatmadaw, and ethnic armed organizations in many parts of the country.

Yet, even with this lacklustre record and the spectre of a pandemic-induced recession, Aung San Suu Kyi remains immensely popular among the Bamar Buddhist majority, who, despite her tarnished image overseas, see her as an icon of democracy. For most people, the prospect of a return to military rule was enough for voters to overlook the NLD’s shortcomings, seeing as it is the only party powerful enough to challenge the military and its proxy party, the USDP.

The system works against ethnic minorities

Remarkably, a country that spent more than 50 years under military rule managed to hold its second democratic election as scheduled without major irregularities – all of this during a global pandemic. While in 2015 the NLD campaigned as an ally of ethnic minorities, the latter have felt increasingly marginalized under the party’s rule. Aung San Suu Kyi has shored up the support of the majority ethnic Bamar Buddhist base, but in the process has also alienated many minorities by failing to include them in decision-making processes. In 2015, the NLD appointed its own members to lead state governments instead of choosing representatives of ethnic parties that had won a majority of seats in these ethnic regions.

Progress on the peace process to negotiate an end to violent conflict with different ethnic groups has been slow and difficult, despite being one of the NLD’s top priorities in the last election. A first-past-the-post electoral system – one in which a candidate with the most votes wins the seat irrespective of the proportion of votes received – rewards big powerful parties like the NLD to the detriment of smaller ethnic parties. With more than 25 per cent of seats reserved for the military and discriminatory citizenship laws that disenfranchise groups not part of Myanmar’s 135 officially recognized “national races,” the cards were already stacked against ethnic minorities vying for representation in parliament.

Of concern is the perceived lack of legitimacy of the election results, which can have long-term consequences for the credibility of the new government. While there is little evidence to suggest that the elections were not ostensibly free and fair, there is no doubt that an uneven playing field heavily favoured the incumbent NLD. Myanmar’s ethnic diversity is not reflected in its majoritarian democracy – hence a failure to consider electoral reform may erode trust in the system and further drive marginalized groups towards other channels to have their grievances heard, including insurgencies.

Extending an olive branch to ethnic minorities

While a peaceful resolution of decades-old ethnic conflicts and electoral reforms may take years to accomplish, the NLD, with its renewed mandate, has the opportunity to make headway on these issues. While it is very early days, in an unprecedented move, the victorious ruling party already reached out to 48 ethnic parties and called for their support in building a federal union. Although it is still unclear how such a partnership would transpire in practice, such an overture is a significant positive step towards ethnic reconciliation.

A few days after the election, even the military has announced its intention to quickly get back to work on solving ethnic tensions by forming a peace negotiation committee to hold talks with ethnic armed groups, regardless of whether or not they are signatories to the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), normally a precondition to participating in government-led formal peace negotiations. It remains to be seen if this renewed commitment to a political solution will produce tangible results, or if talks will stall as they have in the past.

An emboldened NLD and the entrenched military

While the situation with ethnic parties and groups may soon take a more positive turn, the civil-military relationship has worsened in recent years due to mutual distrust and lack of respect. The NLD and the military have had an uncomfortable relationship, underpinned by the 2008 military-drafted constitution that guarantees military control over key ministries: Defense, Border, and Home Affairs. However, since assuming power in 2015, the NLD has not convened a single meeting of the National Defense and Security Council, the highest-level executive body responsible for issues of priority to the military, leading to the perception that the government sidestepped the most critical institution for civilian-military dialogue.

Although the Tatmadaw has no choice but to accept the humiliating defeat of the military-backed USDP in this latest election, it will continue to play an influential role in the country’s politics. In the coming months, the military and the upper and lower houses of parliament will each nominate a candidate for president, who will make virtually all major appointments, including the ministers in a new cabinet. Although the military’s preferred candidate for president may not be selected, it will still retain a large degree of influence because the two unsuccessful finalists will become vice-presidents.

There is a possibility that the Commander-in-Chief, Min Aung Hlaing, whose term will end as the country transitions towards a new NLD government, may take the vice-presidential role. This would allow the already assertive senior general to further push the Tatmadaw's political interests at the executive level.

A post-Aung San Suu Kyi future for the NLD

While the NLD can comfortably head into its second mandate, it will soon have to consider a future after Aung San Suu Kyi, the 75-year-old leader who is well-loved by the many who refer to her as “Mother Suu” and see her as a champion of democracy and the defender of the Burmese nation. In 2018, the NLD made internal appointments that potentially prepare second-generation party members for succession. But it is still unclear who will take up the mantle. With much of the country’s politics centred around personalities, the future leader will undoubtedly have big shoes to fill.

Repairing its relationship with the world

As politicking continues in the capital Naypyidaw, clashes between the military and ethnic armed groups are still ongoing in many parts of the country. Of particular concern is the escalating violence and humanitarian crisis in Rakhine state, which has received much international attention due to allegations of crimes against humanity committed by the military towards the Muslim Rohingya ethnic minority.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s international image has taken a big hit over her response to these allegations, especially when the Nobel Peace laureate vehemently denied genocide charges against her country at the International Court of Justice in December 2019. Whether Aung San Suu Kyi can convert her continued domestic popularity to repair Myanmar’s image abroad remains to be seen. Doing so would require her government to engage with different stakeholders – including ethnic groups, civil society organizations, the military, and foreign countries – on the Rohingya crisis and other ethnic conflicts brewing within the country’s borders. Canada, which has made improvements in the Rohingya situation a major foreign policy goal, will be watching closely for positive signs in the next five-year term.

The author is grateful for the comments and suggestions provided by Election Watch Myanmar team members Tae Young Bae and Matthew Putman.

Other Dispatches in this Election Watch Series:

Election Watch Myanmar (Oct. 8): A Country at War with Itself Goes to the Polls

Election Watch Myanmar (Oct. 30): Balancing Economic Recovery and Social Reform in the Lead-up to the General Election

Election Watch Myanmar (Nov. 6): Three Questions Surrounding Myanmar's General Election