In November 2015, the sense of anticipation surrounding Myanmar’s first genuinely democratic general election in decades was palpable both inside and outside the country. On Sunday, the country will repeat the exercise, although, as others have observed, the mood this time around feels different.

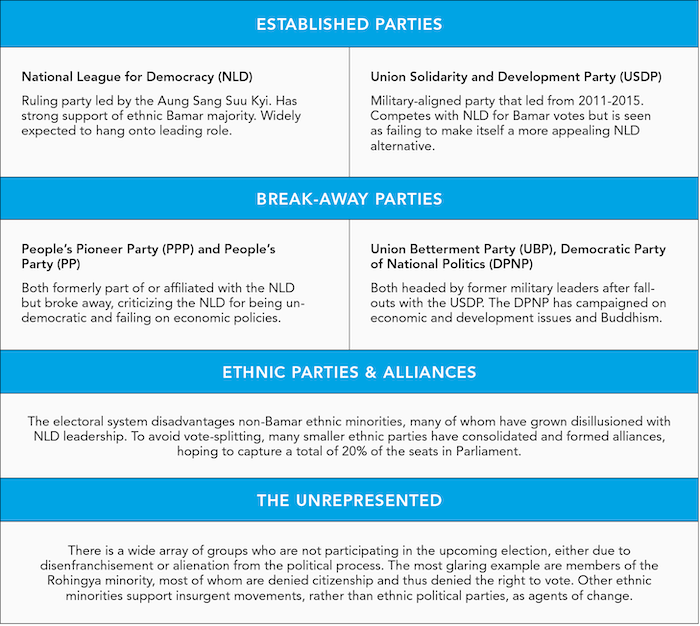

One reason, of course, is the COVID-19 pandemic. Lockdown measures in part of the country have limited the reporting and campaigning that would typically accompany election season. Another reason is the considerable predictability of the results. The military is constitutionally guaranteed 25 per cent of the seats in Parliament, the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) is widely expected to hang onto its lead, and the main opposition party, the military-linked Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), is not likely to be a significant factor as it has mostly failed to burnish its image as a compelling alternative to the NLD.

While the election may not deliver many surprises in terms of outcome, there are nonetheless aspects to watch that could shape the context for an anticipated second NLD-led term. This Dispatch identifies three questions that will be on the minds of voters and spectators alike.

1. Will the election be perceived as free and fair?

It is worth remembering that Myanmar is a young democracy with ample room to grow in terms of institutionalizing the freedoms that define a democratic society. It is also worth remembering that democratization does not always proceed along a linear path. While observers considered the 2015 general election to be relatively free, many have raised concerns about the current environment, particularly ongoing restrictions on freedom of expression, access to information, and shrinking political space ahead of the 2020 general election.

According to Freedom House, a U.S.-based NGO that conducts research and advocacy on democracy, political freedom, and human rights, Myanmar lacks a genuinely free press. Journalists and reporters covering sensitive topics risk harassment, physical violence, and imprisonment under the country’s strict defamation laws. Journalism has been declared a non-essential business by the government, ostensibly to curb the spread of COVID-19 cases, but effectively trapping reporters under stay-at-home orders in large portions of the country, including the largest city of Yangon.

Moreover, with the expansion of internet access in recent years, more and more people in Myanmar have turned to social media, particularly Facebook, as their primary news source. This has facilitated the proliferation of hate speech, including anti-Muslim propaganda and misinformation from groups of all political stripes, which has largely gone unchecked by the government. Internet shutdowns are common in Myanmar’s conflict-ridden regions. They remain in effect in townships in Rakhine and Chin states, where residents face severe limitations in their ability to access important information on COVID-19 and voting.

Other fundamental issues that could undermine the credibility of Myanmar’s electoral process include discriminatory citizenship and electoral laws. These laws are based on the notion of ‘taingyintha,’ or ‘national races,’ which exclude minority groups such as the Rohingya, who are considered foreigners despite being present in Myanmar for generations. On this same basis of citizenship, the Union Election Commission (UEC), Myanmar’s election authority, disqualified opposition party candidates, limiting who can run for office and reducing overall opposition. Although the UEC is supposed to act impartially, it has come under fire for being perceived as doing the NLD government’s bidding. It restricted campaigning by banning rallies and mass meetings, rejected opposition parties’ calls to postpone the election amid rising COVID-19 cases, and selectively cancelled voting in conflict-ridden areas including in Rakhine, Kachin, and Shan states.

These embattled areas also happen to be regions where there are large, ethnic-based parties and where the NLD came up short in the 2015 election. The official reason for cancelling voting in these areas is that active armed conflicts make voting unsafe, but the cancellations are being decided on a township-by-township basis by a partisan UEC. While these decisions are not surprising given the context of a global pandemic and internal armed conflict, the lack of transparency and public debate is alarming particularly as elections were not cancelled in townships where the NLD had a strong showing in 2015. Moreover, due to COVID-related travel restrictions, fewer international observers will be present in Myanmar to monitor the upcoming elections than in 2015.

2. Will ethnic minorities feel empowered or disempowered?

The limitations on freedoms, partisan decision-making by the election commission, and discriminatory laws in Myanmar severely disadvantage opposition parties vying for representation in parliament. These actions have disenfranchised millions of people, particularly those from Myanmar’s many ethnic minorities and, most notably, the Rohingya.

Those who are able to compete in the elections still face significant hurdles. The dominance of the NLD and the USDP is a disadvantage for alternative ethnic minority parties under Myanmar’s first-past-the-post system. The candidate with the most votes wins a seat regardless of the proportion of votes received. This winner-takes-all system continues to marginalize ethnic minorities that have already been disproportionately affected by flawed and discriminatory electoral laws.

In the 2015 election, most ethnic minority parties won only one or a small handful of seats apiece. Thus, expanding their representation at the national level requires forming alliances with other parties in their regions and not contesting seats through bargaining manoeuvres that would avoid splitting the minority ethnic groups’ vote. The merger of ethnic parties in certain states may give them an electoral boost, but it does not mean they will play an essential role as part of a ruling coalition, even if they increase their share of seats. The NLD, with its dominance in the majority ethnic Bamar regions, is likely to achieve the plurality of seats on its own, allowing it to select a president, who makes virtually all appointments at the national and regional levels regardless of how their party performs in the ethnic minority states.

3. Will the election increase or decrease enthusiasm for democracy?

Myanmar’s 2015 elections were a significant step forward along the path to democracy, but this time around, the mood has shifted. The pandemic has made campaigning much more difficult than usual and could reduce voter turnout dramatically. Early voting and absentee voting in Myanmar is somewhat limited, and most people will have to vote in person. With COVID cases currently on the rise, a large-scale outbreak will not only cripple Myanmar’s fragile public health system, but it will also have prolonged consequences for the country’s developing economy.

There is also a faction within the country that is part of a no-vote movement – a small but growing group of activists, journalists and ordinary citizens disappointed by a perceived lack of progress by the NLD on ethnic minority rights, constitutional reform, and economic development. This group has stated that it will not participate in the upcoming election. Senior politicians have swiftly condemned the movement. However, it represents a more profound frustration shared by many with a political system that is still heavily influenced by the military and favours the dominant Bamar ethnic group.

Perhaps the most significant thing to watch in the upcoming election and beyond is whether these issues – reductions in democratic space and ethnic minorities and others who are disillusioned with the ruling government and the democratic process overall – could signal or feed into a democratic erosion. The 2015 elections were conducted under conditions conducive to consolidating Myanmar’s budding democracy, with the NLD riding to victory on the promise of constitutional reforms that would bring the military under civilian control. Five years later, with no major breakthroughs in relations with the military or at the negotiating table with ethnic minorities, this election may further divide rather than unite the people of Myanmar.

The authors are grateful for the comments and suggestions provided by Election Watch Myanmar team member Tae Young Bae.

Other Dispatches in this Election Watch Series:

Election Watch Myanmar (Oct. 8): A Country at War with Itself Goes to the Polls

Election Watch Myanmar (Oct. 30): Balancing Economic Recovery and Social Reform in the Lead-up to the General Election

Election Watch Myanmar (Nov. 17): A Renewed Mandate for the Returning Party