The Takeaway

New Delhi’s recurring air pollution crisis shows no signs of abating. Recent alarming levels of pollution have forced a suspension of many daily activities and put the health of the city’s 33 million inhabitants at risk. Vehicle emissions are one contributing factor, but so is stubble-burning, or the intentional burning of crop debris after harvesting grains like rice and wheat. Stubble-burning happens in several neighbouring states, making it a multi-jurisdictional problem with no easy solution.

In Brief

-

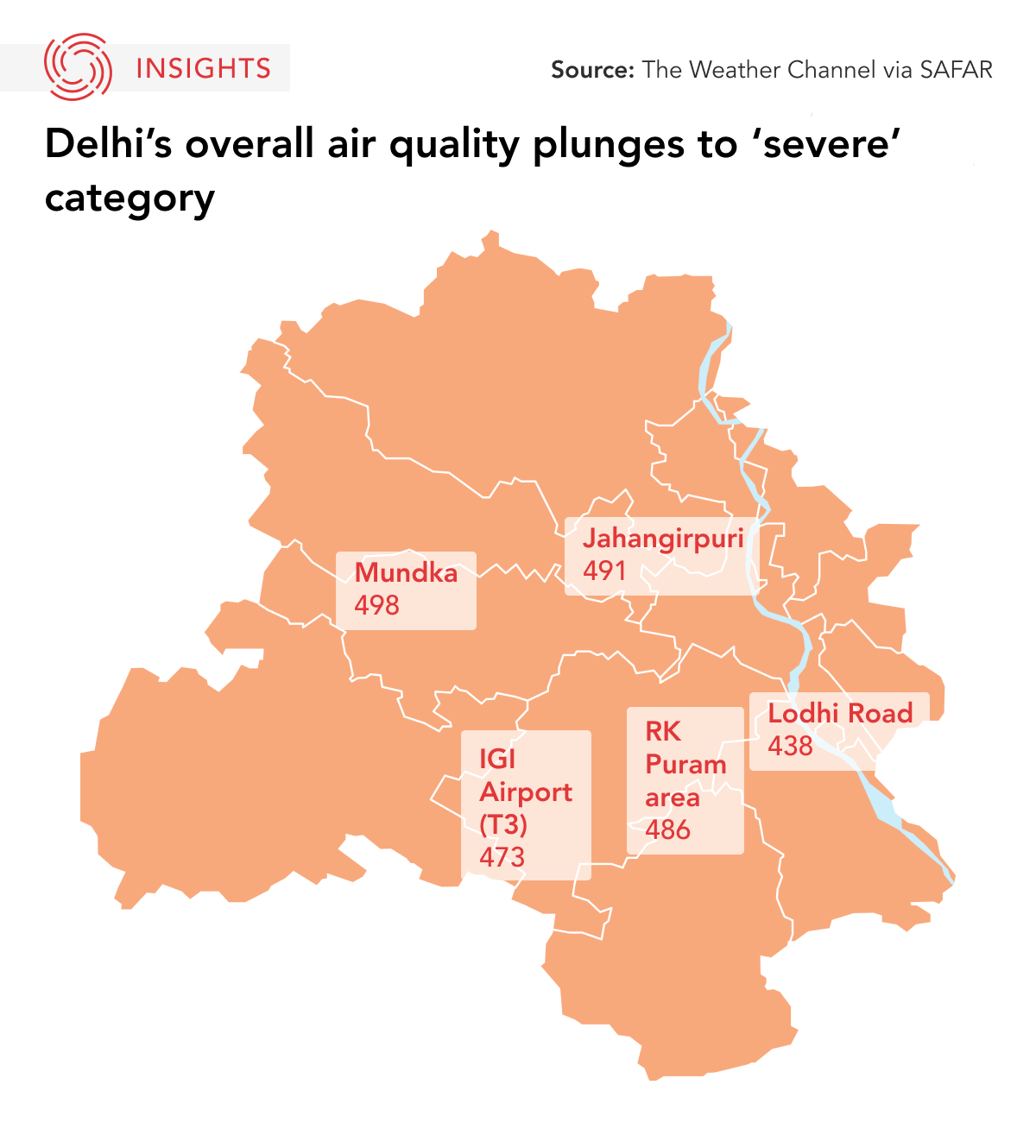

On November 3, New Delhi’s air quality index (AQI) hit 500, the highest possible measurement and 100 times the World Health Organization's 'safe' limit. The Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC) has suggested that based on trends from previous years, pollution levels in the city could peak between November 1 and November 15, coinciding with the increase in stubble-burning in the neighbouring states of Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan. As of November 15, although Delhi’s AQI has improved slightly to 390 — considered “severe” — it is still not out of the woods.

-

On November 7, the Supreme Court of India ordered the governments of Delhi, Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh to immediately ban crop burning. While there has been a decline in farm fires in some states since 2022, others have seen no such decline.

-

New Delhi is not the only Indian mega-city grappling with this issue. Mumbai’s air quality is also deteriorating, with some parts of the city of 21 million recording an AQI of 180 — roughly five times higher than New York City (34) and three times higher than Tokyo (58). In response, the Maharashtra state government has implemented a “health action plan” and has advised citizens to stay indoors.

Implications

-

Premature deaths and serious diseases

Air pollution is known to cause severe respiratory infections, including lung diseases, asthma, and bronchial diseases, as well as serious cardiovascular and gastrointestinal issues. One Indian media outlet, using national health-care data, estimated that in 2019, air pollution-related diseases cost India US$12 billion (999.8 billion Indian rupees). In an interview, K. Sujatha Rao, India’s former union secretary for the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, noted that air pollution is India’s third-highest mortality factor.

-

Steep economic costs

Air pollution lowers worker productivity and suppresses consumer spending when it reaches levels that force businesses to suspend their operations. The cost from these and other factors to the Indian economy is estimated to be US$95 billion (7 trillion Indian rupees) each year, roughly three per cent of the country’s GDP. The Reserve Bank of India estimates that if the pollution problem is not addressed promptly, this number could rise to 4.5 per cent of India’s GDP by 2030.

-

Piecemeal policy responses

To reduce vehicle emissions, the Aam Aadmi Party-led (AAP) Delhi government introduced the ‘odd-even’ vehicle rationing scheme previously, restricting even-numbered licence plates to run on even dates and odd-numbered plates on odd dates. After suggesting a revival of the scheme, the government subsequently withdrew its commitment. The Delhi government is, however, monitoring a temporary ban on construction and demolition activities in severely polluted areas and has deployed surveillance teams to ensure compliance. Overall, such measures have been far from sufficient. In addition, India’s 2019 National Clean Air Programme has been largely unsuccessful due to a lack of funding for sustainable infrastructure and the government’s failure to regulate major polluting industries.

What Next

1. Political blame game hinders progress

The Delhi government’s environment ministry, headed by the AAP, is locking horns with the DPCC. The DPCC is appointed by the central government, which is headed by the Bharatiya Janata Party. The Delhi government’s environment ministry has accused the DPCC of withholding funds for a vital air pollution study. If partisan interests and struggles over bureaucratic control are not reined in, efforts to address New Delhi's severe air quality issues will remain inadequate, posing a serious setback to mitigating pollution in the world's second-most polluted city.

2. Crisis demands collaboration between state governments

Most immediate measures have failed to bring the pollution problem under control. The government must introduce more fundamental policy-level changes and year-round solutions like other cities with high pollution levels. This includes, for example, Beijing, which introduced emissions regulations for vehicles and the automotive manufacturing industry, and London, which introduced low-emissions zones. Governments may seek to promote sustainable alternative farming practices — such as converting straw into pellets or organic fertilizer — over stubble-burning and farm fires, which are major causes of air pollution outside of vehicle emissions.

• Produced by CAST’s South Asia team: Suvolaxmi Dutta Choudhury (Program Manager); Prerana Das (Analyst); Suyesha Dutta (Analyst); and Deeplina Banerjee (Analyst). Edited by: Ted Fraser. Design by: Chloe Fenemore.