When the results of India’s national election were announced on June 4, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) — politically dominant for a decade and, to some, seemingly invincible — may have greeted the news with mixed emotions.

While Indian voters handed the National Democratic Alliance, a BJP-led alliance, its third term, voters also significantly reduced the party’s share of seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament. But amid the humbling election results was a bit of recent good news for the Indian government: for the fiscal year ending March 2024, the Indian economy grew at an “eye-popping” 8.2 per cent, up from seven per cent a year earlier. This growth was reportedly fuelled, at least in part, by state spending on infrastructure and “momentum in manufacturing and construction.” If such growth rates continue, India will remain on track to become the world’s third-largest economy by 2027.

Canada recognized India’s immense potential in its 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy, noting that the country’s “growing strategic, economic and demographic importance in the Indo-Pacific make it a critical partner” for Canada and its wider objectives in the region. Ottawa reiterated this conviction during the Canada-India Ministerial Dialogue on Trade & Investment, held in May 2023. Official diplomatic relations took a nosedive in September 2023, however, after Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau stated that Canada had “credible allegations” that the individuals responsible for the June 2023 murder of Canadian citizen and Khalistani activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar had links to the Indian government. The fallout from these allegations was immediate, including postponement of a Team Canada Trade Mission to India, which had been planned for later in 2023, and a pause in discussions on the two countries’ Early Progress Trade Agreement (EPTA), which was supposed to conclude by 2023.

What do bilateral trade and investment data tell us about the trajectory of Canada-India economic relations prior to the diplomatic rupture in September 2023? And what do we know so far about how economic ties have — or have not — been impacted by these political tensions, and why?

In brief, the data show that thus far, economic ties have not been impacted significantly, likely due to two factors: consistency in the supply and demand on both sides, and a lack of signalling by either government that they intend to take steps to hamper business ties.

Steady growth in trade

Over the past decade, Canada-India two-way trade in merchandise nearly doubled, from C$6.4 billion in 2014 to C$12.67 billion in 2023. As shown in Figure 1, in 2022, two-way trade jumped by 52 per cent year-on-year, partly driven by increased global demand during the post-COVID-19 recovery.

In 2023, trade patterns began to normalize, with Canadian exports to India dropping by four per cent and imports from India dropping by nine per cent year-on-year. In September 2023, when the Nijjar allegations created a major rift in the bilateral relationship, aggregate worldwide trade volume was already 3.5 per cent lower than a year earlier due to several changing economic conditions: increased protectionist sentiments, also sometimes referred to as trade ‘reshoring’; the rising cost of living; dampening consumer demand due to inflation; and contracting global output. In 2023, Canada’s exports to India were more stable than its imports, even though Canada does not enjoy export exclusivity to the Indian market for any particular commodity.

What does a more granular look at this trade relationship tell us?

From 2014 to 2023, Canada’s exports to India were dominated by three sectors: metal ores and non-metallic minerals (C$11 billion), farm and fishing food products (C$7.56 billion), and energy products (C$7.55 billion). This includes large shipments of bituminous coal from British Columbia, potassium chloride from Saskatchewan, and unsorted diamonds from the Northwest Territories.

In contrast, Canada’s imports from India were dominated by consumer goods (C$24 billion), metal and non-metallic mineral products (C$5.4 billion), and chemical, plastic and rubber products (C$4.9 billion).

Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, demand for consumer products has grown stronger over time, corresponding with the tripling of immigration from India to Canada in the past decade. For example, the main imports from India included jewellery, worked diamonds, long-grain rice, and medicinal products, and were primarily destined for Ontario and British Columbia, both of which have large Indian diaspora communities.

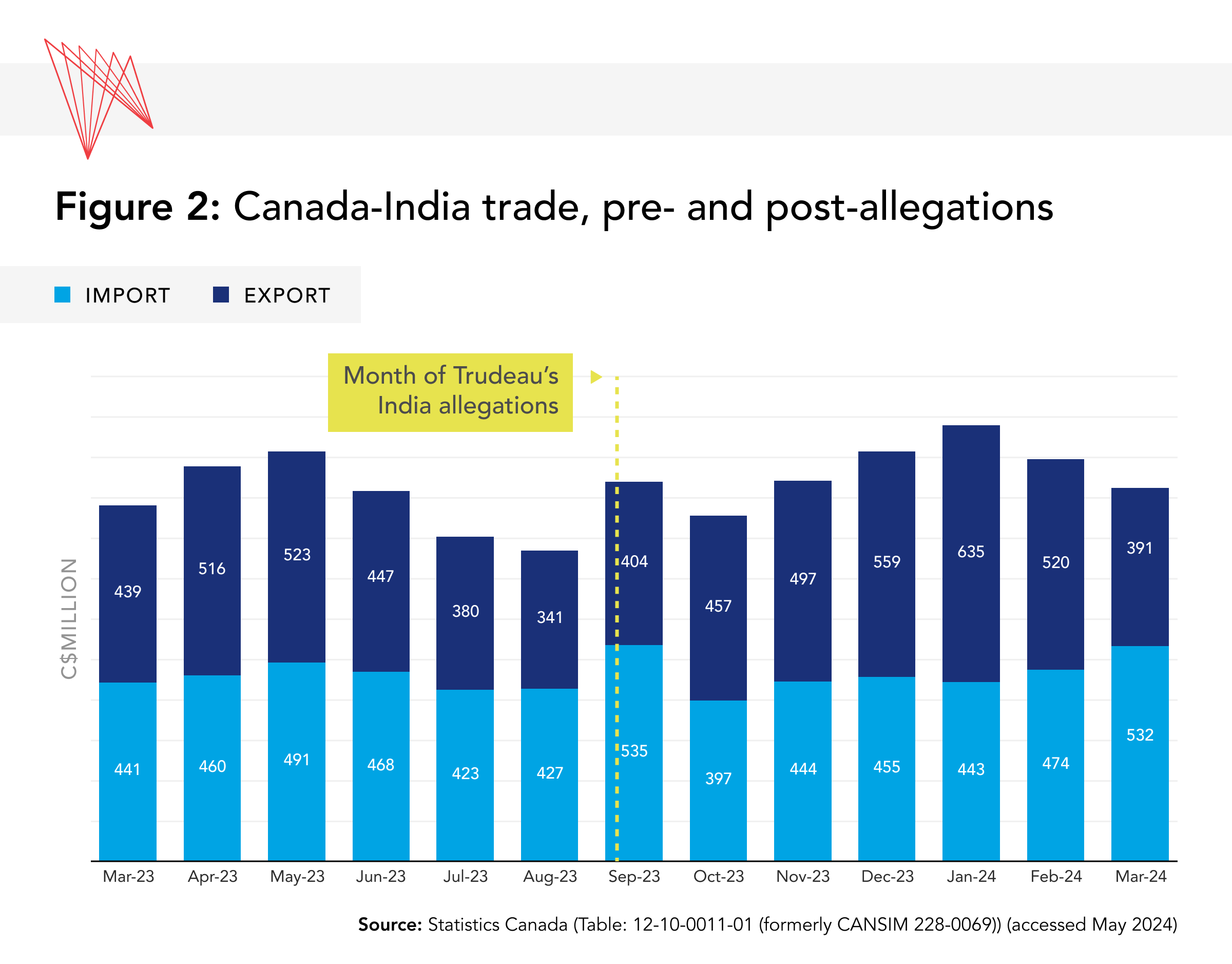

The recent diplomatic strains have had limited impact on trade — so far. Defying most expectations, total two-way trade between Canada and India actually increased slightly — from C$880 million to C$923 million — from March 2023 to March 2024 (Figure 2).

For example, in the six months prior to the Nijjar allegations (March-August 2023), Canadian imports from India were C$2.71 billion, then rose to more than C$2.74 billion in the six months following the allegations (October 2023-March 2024). During that same period, Canadian exports to India increased by roughly 16 per cent, from around C$2.6 billion to around C$3.1 billion.

One driver of this steady trade relationship is the Canadian agriculture industry, which continues to prioritize trade with India. This commitment was reaffirmed when Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe visited India in February 2024 to strengthen agri-food and energy-security ties and to participate in the Raisina Dialogue, India’s premier global forum.

Canada’s lentil exporters have urged the federal government to restart trade negotiations with India. Canada currently accounts for more than half of India’s lentil imports, and in spite of the frosty bilateral relationship, these export levels have largely persisted. Although Indian offer-prices for Canadian supplies dropped by six per cent in September 2023, Canadian exporters have also benefited from an import duty exemption on lentils that the Indian government extended from December 2023 until March 2025.

However, Canada risks losing its market share for lentils to competitors such as Australia. As Australia's production grows and Canada's production experiences a shortfall, the market is becoming increasingly competitive. Since 2019, Australia has steadily increased its lentil exports to India. Although the impact on Canadian lentil exports has not yet been significant, any further escalation in diplomatic tensions could erode the confidence of Indian importers, who now have the option to turn to Australian suppliers. Neither Ottawa nor New Delhi has yet signalled an intention to limit trade for political reasons, suggesting that there may be a mutual recognition of the importance of insulating the economic relationship from the diplomatic fallout.

Investors take a ‘wait-and-see' approach

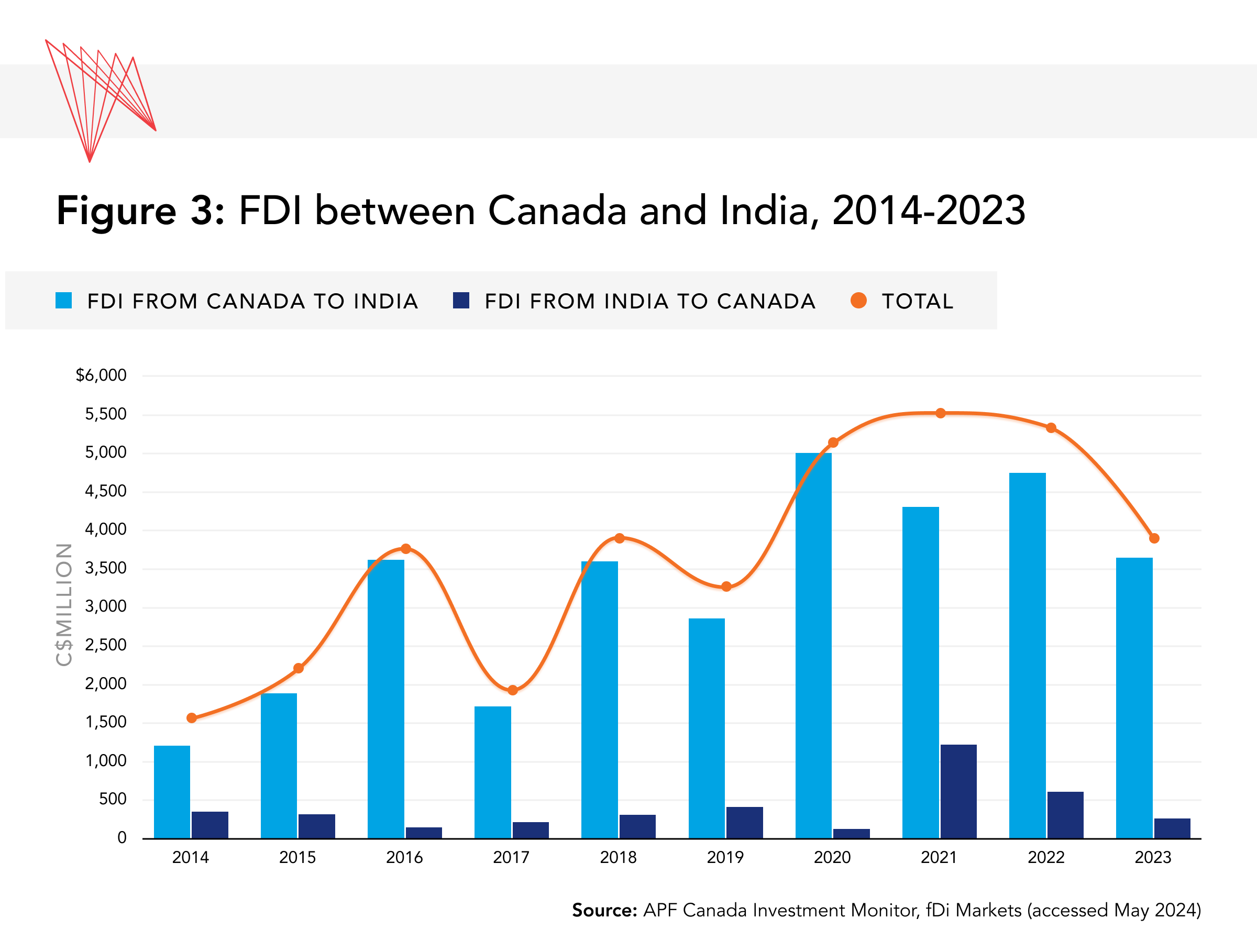

Canadian investment in India increased significantly starting in 2020, perhaps reflecting Canadian investors’ growing optimism about India’s economic potential. Given that investments generally involve long-term commitments of capital, Canadian investors, like investors in other countries, previously exercised some degree of caution with respect to India. However, the BJP government's economic liberalization policies have opened up a variety of sectors to foreign direct investment (FDI) over the past decade, such as infrastructure and food processing. Canadian companies responded to this opportunity, and consequently, Canada and India invested around C$36.5 billion in each other’s economies from 2014 to 2023, growing from C$1.55 billion in 2014 to C$3.9 billion in 2023.

As Figure 3 shows, the vast majority of these FDI flows — around 90 per cent — were Canadian investments in India. Canada’s investment in India hit an all-time high in 2020 with Brookfield Asset Management’s C$3-billion acquisition of RMZ Corp, India’s largest realty portfolio. The recent growth in Canadian investment also includes pension fund investments, including C$11.9 billion invested in India in the last five years alone (2019-23).

However, there have also been some sizable Indian investments in Canada, including investments totalling C$1.2 billion in Mississauga, Ontario, in 2021 by Indian IT giants such as Infosys and HCL Technologies.

However, while Canadian investors have become more focused on the Indian economy, they have also remained somewhat cautious. Canada is not unique in this approach: according to a recent UN Investment Trends Monitor report, India’s overall inflow of FDI — that is, investment from all foreign sources — fell by 47 per cent from 2022 to 2023. Similarly, Canada’s FDI in India also dropped during this period, from C$5.3 billion to C$3.9 billion.

There are several reasons for this trend. First, the deteriorating economic and geopolitical environment, including the Russia-Ukraine war, rising food and energy prices, and tightening financial conditions such as inflation and high interest rates, deterred investors from the markets globally, especially in developing countries.

Second, in the years immediately preceding a national election, investors tend to take a ‘wait-and-see' approach, hoping to avoid any regulatory uncertainties that might accompany a change in government policy. This was also the case prior to India’s 2019 national election, when foreign investments declined from the 2018 level, as investors awaited signs of stability and predictability in the investment environment.

Given the many factors that could suppress Canada-India investment in the short term, it would be premature to attribute any recent declines in investment to the current diplomatic dispute. The impact of the dispute, if there is one, will need to be evaluated in the long term once more data becomes available.

In the meantime, while Canada's current FDI represents only 0.57 per cent of India's total FDI inflow, Canadian investments in India's energy sector and, reciprocally, India's investments in Canada's technology and resource sectors, could support the two sides’ broader strategic objectives: Canada can reduce its dependence on the U.S. for energy exports, while India can try to meet its growing energy demand.

Political signalling, as indicated in May by Indian Minister of External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, suggests that the Indian government expects foreign investment to increase after the national elections concluded in early June. However, FDI growth may continue to be modest over the next couple of years as investors seek clarity and assurance on the new policies and on the state of the Indian business environment created under India’s new coalition government.

While there was significant media attention surrounding the plummeting of the Bombay Stock Exchange on the day the June election results were announced, the long-term outlook remains cautiously positive, as capital expenditure is predicted to increase in response to India’s strengthening economy.

Keeping India high on Canada’s agenda

While the two governments begin getting their formal diplomatic relationship back on track, numerous other stakeholder groups, especially subnational governments and non-governmental bodies, are being proactive in exploring and forging stronger business ties. For example:

- Opportunities New Brunswick, the province’s economic development agency, is looking to engage increasingly with India’s farming, forestry, and fishery markets.

- The 2022 Quebec Strategy likewise stated the province’s desire to enhance relations with India on a multisectoral level, notably in the ICT and pharmaceutical sectors.

- Export Development Canada, Canada’s export-credit agency, has increased its investments in India (and also identified India as a place of opportunity for Canadian companies in its 2024 report).

- Canadian business chambers such as the Indo-Canadian Business Chamber and the Canada-India Business Council have also been active in promoting interaction between stakeholders in the two economies, including the latter’s visit to India earlier in 2024.

- Air Canada, perhaps sensing that Canada-India ties will remain robust, at least on a people-to-people level, recently announced that it is introducing non-stop flight service from Toronto to Mumbai.

In addition to these initiatives, Canadian stakeholders will likely continue to pay close attention to other opportunities for expanding Canada-India economic collaboration. India is steadily diversifying its manufacturing in semiconductors, automobiles, and energy solutions in hopes of taking advantage of the move by many companies to seek an alternative to China as part of their ‘China+1’ strategies.

New Delhi has also expedited free trade agreements with other partners, including the Trade and Economic Partnership Agreement (TEPA) with the European Free Trade Association (comprising non-EU members Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland) and the Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA), to help meet its export target of C$2.7 trillion by 2030. India is near finalizing FTA negotiations with the U.K. and is in discussions with the European Union for both an FTA and an Investment Protection Agreement.

Despite India's tendency towards import restrictions and a trade policy that leans towards promoting exports, its pursuit of several FTAs with Western economies indicates a willingness to embrace liberalization and the West’s welcoming of India as an important player in the global economy.

If Canada and India can eventually conclude the EPTA, leading to a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), two-way trade could be boosted by as much as C$8 billion over the next decade. The result would be an increase in bilateral trade in products with high export potential, including commodities such as gold, potassium, and wood pulp. India also has unmet potential in the Canadian market for motor vehicles, medicinal products, and frozen shrimp and prawns, among others.

To finalize the trade agreement, Canadian officials will need to focus on resolving existing issues and building trust with their Indian counterparts. There is significant potential for the two economies to collaborate in sectors of mutual interest such as clean technologies for infrastructure development, critical minerals, electric vehicles and batteries, renewable energy, and artificial intelligence.

However, successful collaboration hinges partly on the economic agenda, priorities, and reforms of India’s incoming coalition government.

• Edited by Vina Nadjibulla, Vice-President Research & Strategy; Erin Williams, Senior Program Manager, Asia Competencies; and Ted Fraser, Senior Editor. Graphic Design: Chloe Fenemore.