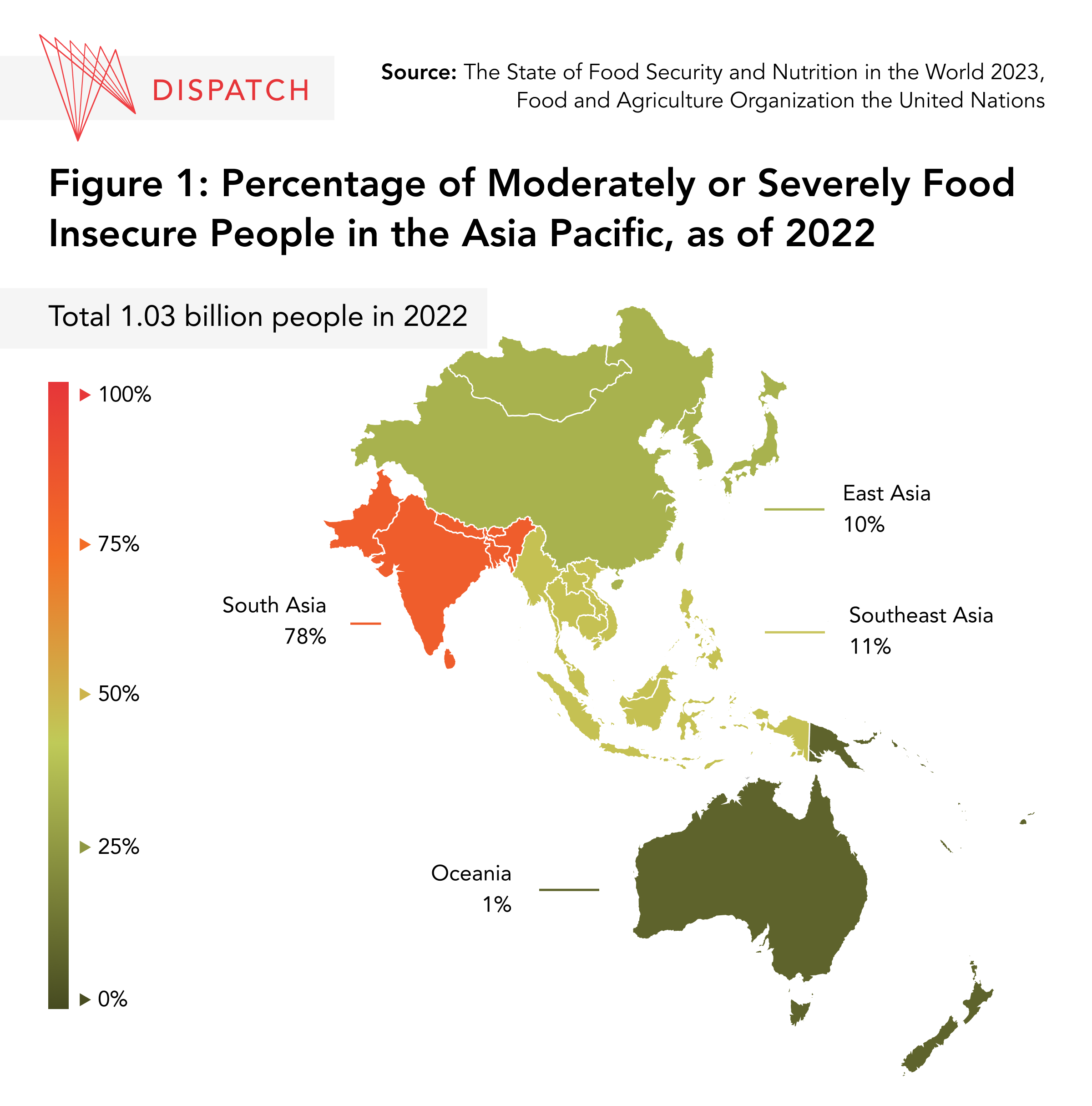

In 2022, 1.03 billion people in the Asia Pacific faced severe or moderate levels of food insecurity. Of that number, 76 per cent were in South Asia and 13 per cent in Southeast Asia (see Figure 1). Food insecurity — defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations as the lack of regular access to enough safe and nutritious food for normal growth and healthy life — in these two sub-regions will be exacerbated in the coming years by growing populations, rising middle classes, and climate change. Their reliance on imports of agricultural products, therefore, is likely to increase significantly.

As part of its Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS), Canada has committed C$31.8 million over the next five years to expanding trade in agriculture and agri-food products in the region to assist in alleviating food security challenges. As a sign of this commitment, on June 7, Ottawa announced that Manila, Philippines, will be the location of Canada’s first Indo-Pacific Agriculture and Agri-Food Office (IPAAO). While the IPAAO represents a significant ‘step up’ in regional engagement, further measures can be taken to boost Canada’s agriculture trade footprint in the region. These include focusing on the sub-regions (i.e. South and Southeast Asia) where the demand will be greatest and planning around short-term, medium-term, and longer-term opportunities for Canadian businesses and policymakers.

Asia’s search for a reliable agricultural supplier amid rising food demand

The rapidly rising middle-income population in Asia’s emerging economies is driving up the demand for food, which typically grows in the early stages of a country’s economic development. The Asia Pacific’s share of the global middle class is forecast to grow from 54 per cent in 2020 to 65 per cent by 2030. As incomes rise and urbanization trends continue, the middle classes in these emerging economies, including in India, Indonesia, and Vietnam, are able to enhance their diets to include more nutrients, including proteins and fats and vitamins found in fruits and vegetables. These changes in demand, moreover, are happening as climate change is likely to decrease the region’s own food production by destroying arable land.

As Asia Pacific countries search for reliable suppliers of agricultural commodities, Canada’s export-oriented agriculture and agri-food sectors are well positioned to bridge the demand-supply gaps and alleviate growing food insecurity in some of the region’s fastest-growing consumer markets.

Canada’s agriculture export potential in the Asia Pacific

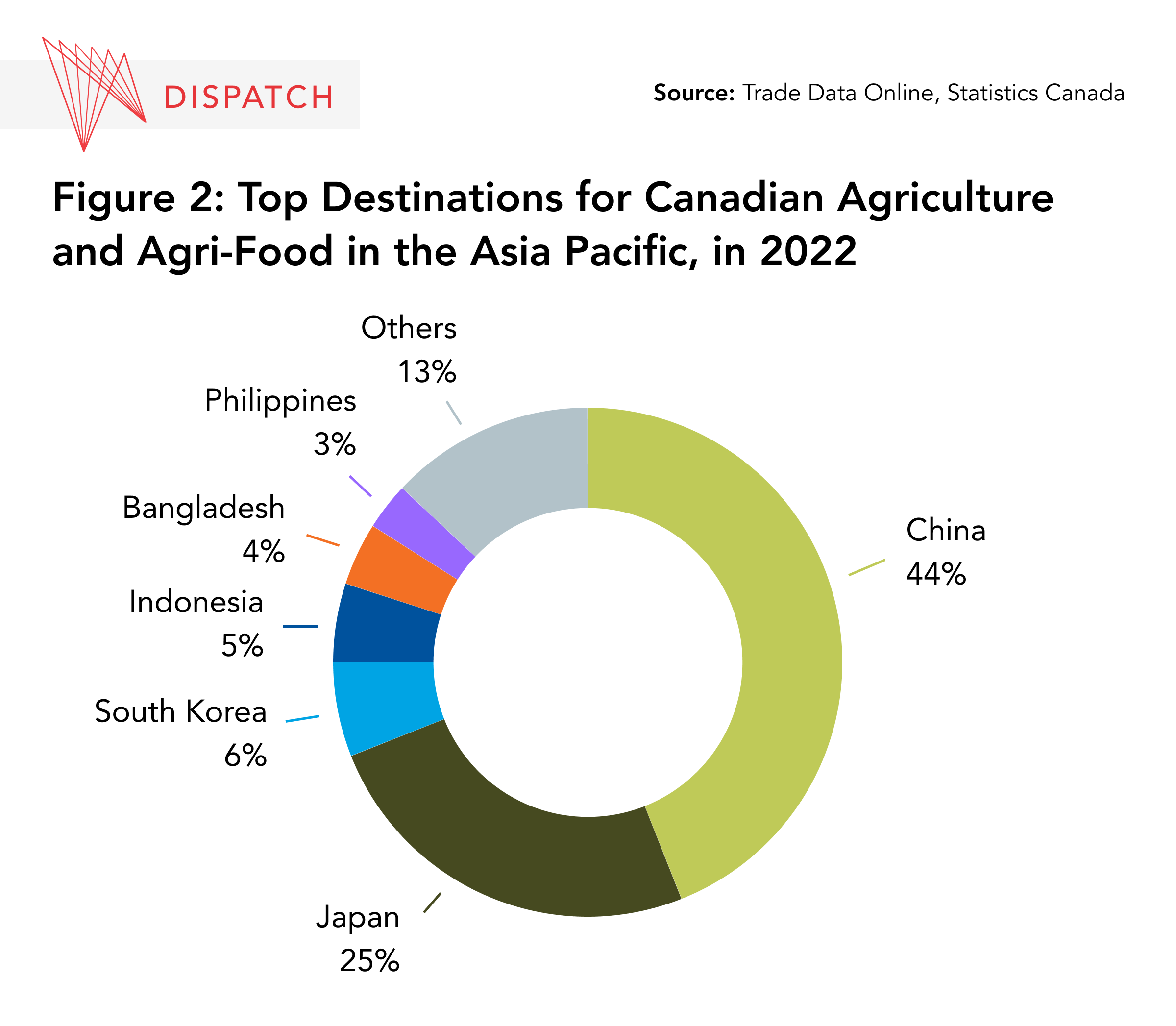

In 2022, the Asia Pacific was the second-largest destination for Canadian agriculture and agri-food exports, with exports reaching C$21.8 billion. Over the last five years, these exports expanded by seven per cent on average per year, signalling moderate growth. China was Canada’s largest Asia Pacific agri-trade partner, with exports reaching C$9.5 billion in 2022. Japan and South Korea, two of the region’s more advanced economies, were the second and third, with Japan accounting for C$5.4 billion and South Korea for C$1.3 billion in agriculture exports (Figure 2) [1].

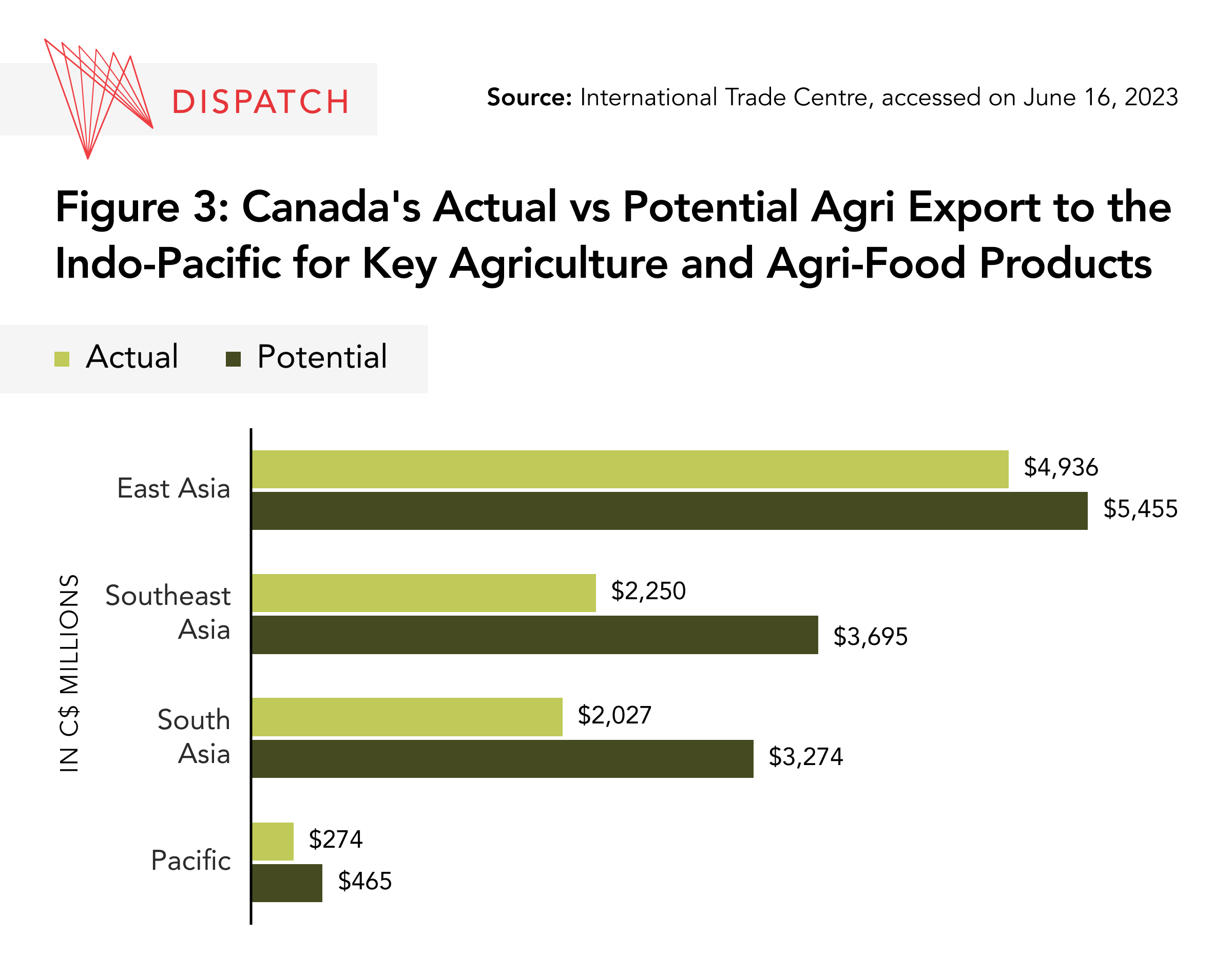

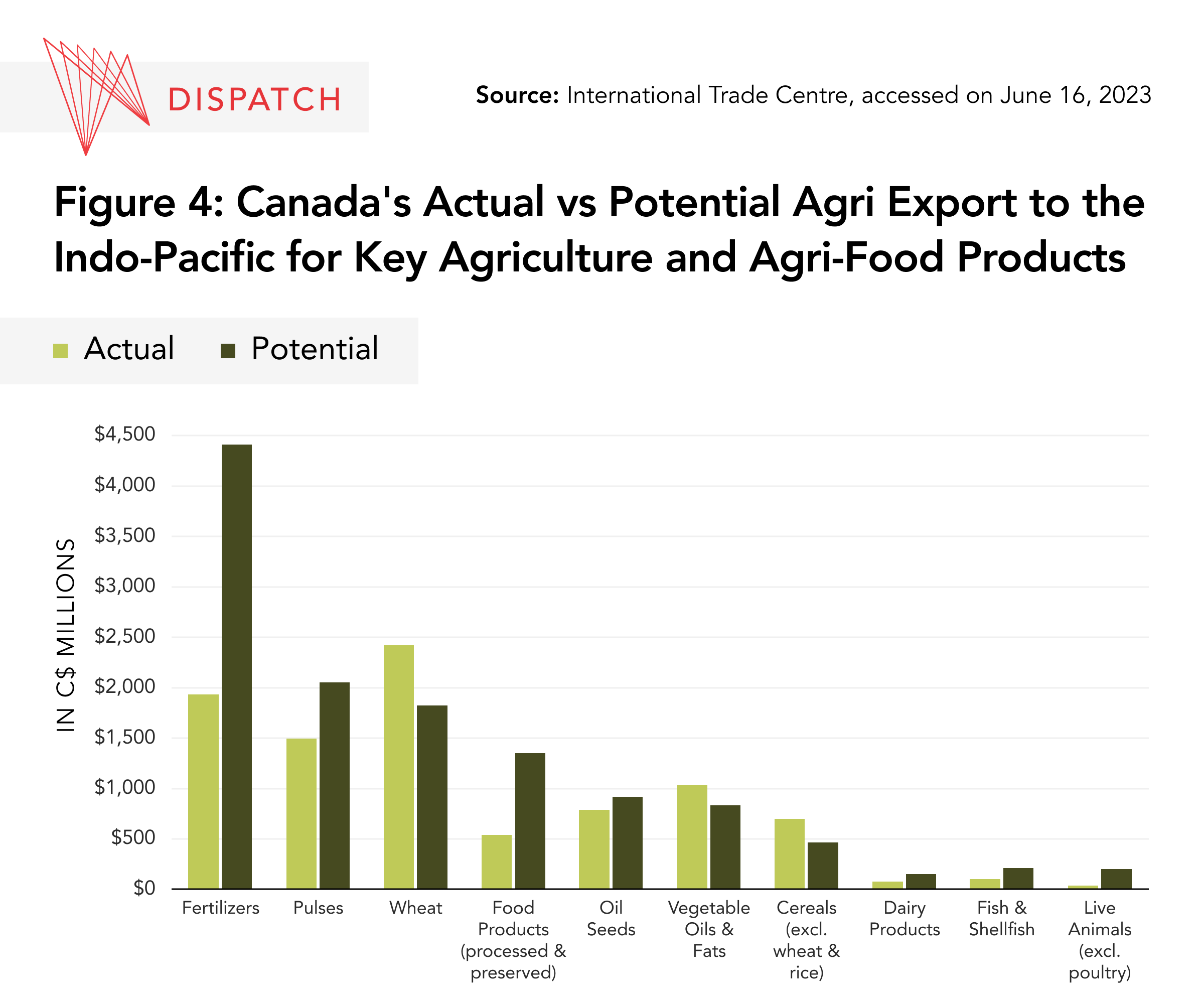

Tools that map trade potential show that Canadian agriculture exports have historically underperformed in major Asia Pacific markets, especially in Southeast and South Asia – the two sub-regions where food insecurity is especially acute. The export-potential tool [2], developed by the International Trade Centre (ITC), a multilateral organization specializing in trade, reveals that Canadian fertilizers, pulses, and preserved and processed food products have the most export potential in the Asia Pacific, among other products (Figure 3). Clearly identifying the region’s agriculture needs and juxtaposing them against Canada’s available products is an important step to better understanding the unmet potential and boosting agricultural trade with the region.

Factors impeding trade

Despite the immense potential, there are several obstacles to increasing Canada’s agricultural exports to the Asia Pacific. These obstacles include a lack of market research, difficulties finding the right buyers, and increased non-tariff trade barriers (NTBs). Regulations in agriculture-importing countries, in the form of NTBs, have been a particular challenge restricting Canada’s agricultural exports to the region. For instance, Indonesia, a large Muslim-majority country, requires halal certification for meat and other food products, a certification many Canadian products do not have. Some countries also impose restrictions based on local sanitary practices. India, for example, requires shipments of pulses to be fumigated with methyl bromide at the point of origin to control stem and bulb nematodes (i.e. roundworms). Additionally, developing countries may impose restrictive measures on foreign agricultural products to safeguard their domestic farming industries.

The ITC tool indicates that, when looking at Canada’s top 10 agriculture and agri-food exports, actual agriculture exports in East Asian markets closely match our potential. Canada's longstanding trade relations with East Asian markets, including China, Japan, and South Korea, and the presence of federal and provincial trade facilitation offices in the subregion are often cited as the key drivers behind Canadian agri-exports’ good performance. In contrast, Canada has a long way to go to reach its potential in Southeast and South Asian markets (see Figure 4).

Reducing barriers, forging partnerships

To unlock the full potential of Canada’s agriculture exports, especially in South and Southeast Asia, Ottawa should work with its government counterparts in these regions to minimize trade barriers and build a supportive and inclusive trade network. In the following paragraphs, we discuss some possible strategies for Canada.

In the short term, the ITC’s gap-analysis of regional trade potential shows that Indonesia could benefit from Canadian soybean exports, while Vietnam’s growing demand for protein can be addressed by Canadian exports of seafood and pork. India and Bangladesh, two South Asian economies with growing populations and decreasing arable land, can benefit from Canadian potash fertilizers.

In the medium term, Canada should focus on building its knowledge and resource capacity with the support of academics, exporter associations, and think-tanks. Sharing knowledge and information about local agriculture markets and trade requirements can help Canadian companies expand to new markets. For instance, Canadian beef and processed food producers interested in exporting to countries with halal requirements could benefit from assistance in knowing how to get the required certifications.

In the long term, Ottawa should continue negotiating mutually beneficial free trade agreements (FTAs) and reducing tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade. As Canada is currently negotiating trade deals with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), India, and Indonesia, Canadian agriculture and agri-food exporters will benefit from the guidance and predictability provided by these future trade deals. For instance, India’s pulse fumigation requirement has limited the export of Canadian pulses to India since 2004, although Canadian pulse exporters have managed to negotiate temporary exemptions. A Canada-India Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement could include the permanent removal of the fumigation clause, creating more certainty for Canadian exporters.

Canada’s new agriculture office in the Philippines and the establishment and expansion of regional networks represent the second component of a strong long-term strategy as they will help prevent information asymmetries, such as in the Canada-India discord over pulses. Through information sharing, Canadian officials may prevent (or provide a faster resolution to) NTBs. The agriculture office in Manila will be able to answer regional partners’ questions on sanitary and phytosanitary measures to assure consumers that Canadian products are safe, and explain other technical requirements, resulting in a quicker resolution to NTBs. This would have been useful in the case of Indian pulses, given that the pest identified by Indian policymakers for fumigation does not exist in Canada, and the fumigation chemical required by India to treat the pest is illegal in Canada.

Canada’s strong performance in East Asia, mainly in China, is connected to the heightened presence of the Canadian government and businesses in the region compared to the rest of the Asia Pacific. Considering Canada’s commitment, as articulated in the IPS, to diversify trade beyond China and partner with critical partners like ASEAN and India, the time is ripe for Canada to expand its presence in other key markets across the broader region.

Conclusion

The Asia Pacific, home to some of the world’s fastest-growing consumer markets, is facing an unprecedented demand for agriculture and food products. Although Canadian agriculture and agri-food exports have historically underperformed in this region, establishing the IPAAO in Manila opens a unique window of opportunity for Canadian agri-exporters. Targeting export-dependent countries and building capacity in the short and medium term, in addition to negotiating trade deals and leveraging the IPAAO to create new market access and remove trade barriers, can help Canada revamp its agriculture and agri-food exports to the Asia Pacific. Ottawa should prioritize facilitating agriculture trade with the region to maintain momentum and establish Canada as a preferred supplier in the region.

Endnotes:

1. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada include the following NAICS codes under agriculture and agri-foods — 111 Crop Production, 112 Animal Production and Aquaculture, 114 Fishing, Hunting and Trapping, 311 Food Manufacturing, and 3253 Pesticide, Fertilizer and Other Agricultural Chemical Manufacturing. These codes were used to generate the figure.

2. The ITC Export Potential Tool deploys the gravity model of trade and considers three things — exporting country’s supply capacities, demand conditions in the target market, and bilateral relations between the two trading partners. ITC takes the average from the period 2017-2021, giving higher weights to more recent data. Considering forward-looking variables like projected GDP and population growth and scheduled tariff reductions, ITC estimates a benchmark potential export value that a country can achieve for a given product and export market in the year 2027. As the Export Potential Map does not account for upcoming developments, including new trade agreements or any disruptive events, the tool only serves as a starting point in the decision-making process and should be complemented with further research and stakeholder consultations.