The cross-border movement of goods and services has grown rapidly since economies began opening their markets to global trade in the latest wave of globalization starting in the 1990s. However, as products cross borders, they are subject to trade and regulatory barriers imposed by the importing country, including tariffs and licences. These barriers increase costs and may even restrict the import of some goods. Canadian canola producers, for example, faced a three-year ban on canola exports to China after Chinese authorities withdrew import licences from Canadian companies in 2019. During the same year, Canada-China bilateral relations deteriorated with the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver (on a U.S. extradition warrant), making it difficult to resolve trade disputes. Canadian canola farmers lost more than C$2 billion during the first two years of those import restrictions due to lower prices and foregone sales.

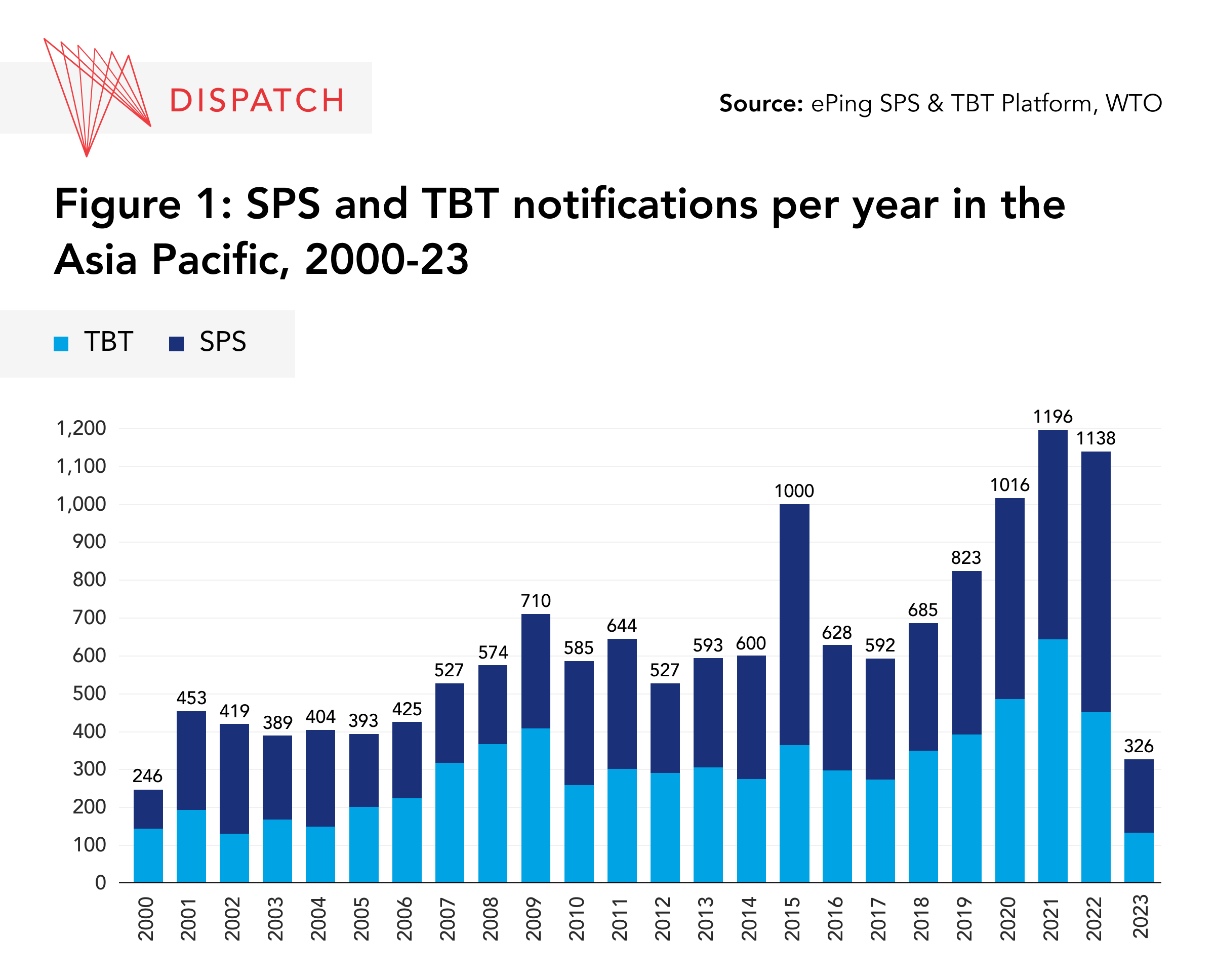

As the canola example illustrates, non-tariff barriers (NTBs) increase the costs of trade for Canadian businesses in the Asia Pacific. The UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) estimates that NTBs have affected around 58 per cent of Asia Pacific trade. According to the International Trade Centre, a multilateral agency under the UN and World Trade Organization, Asia Pacific economies have imposed around 25,000 NTBs, and their yearly use of certain barriers has grown from fewer than 300 measures in 2000 to more than 1,000 in 2020 (Figure 1).

For Canada, lowering, eliminating, or harmonizing NTBs (or ensuring that NTBs are similar across countries) is an important dimension of expanding trade with the region, especially in light of Canada’s 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy, which identifies trade and supply chain resilience as one of its core strategic objectives. Canada’s current and future free trade agreements (FTAs) in the region are an opportunity to address these barriers. To benefit from FTAs, policymakers must consider the following: How effective are Canada’s existing FTAs, such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Canada-Korea Free Trade Agreement (CKFTA), in dealing with NTBs? And how can NTBs be addressed in Canada’s ongoing FTA negotiations with Indonesia and the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)?

Canada-Asia Non-Tariff Barriers to Trade

NTBs take many forms. These include regulatory barriers, such as administrative procedures or quotas; technical barriers to trade (TBTs), such as legal requirements; and sanitary and phytosanitary (i.e. related to the safety of plants) measures (SPSs). About half of the NTBs imposed by Asia Pacific economies in the past two decades are technical barriers.

These NTBs are often imposed over legitimate concerns for human welfare and the environment, such as restrictions on genetically modified organisms in certain countries. Labelling and certification requirements implemented to demonstrate that imported products conform to human welfare and environmental regulations in the importing countries are further examples of NTBs. However well intended, these requirements can also distort trade by making it more costly and difficult, especially for exporters seeking to enter new markets and for importers who have to pay higher prices for goods. According to some estimates, NTBs cost two to three times as much as formal trade barriers, given that they increase the costs of production and compliance. A UNESCAP study found that NTB regulations vary across the Asia Pacific, increasing trade costs by about 8.2 per cent for technical measures and 7.1 per cent for non-technical measures.

NTBs in Asia’s Free Trade Agreements

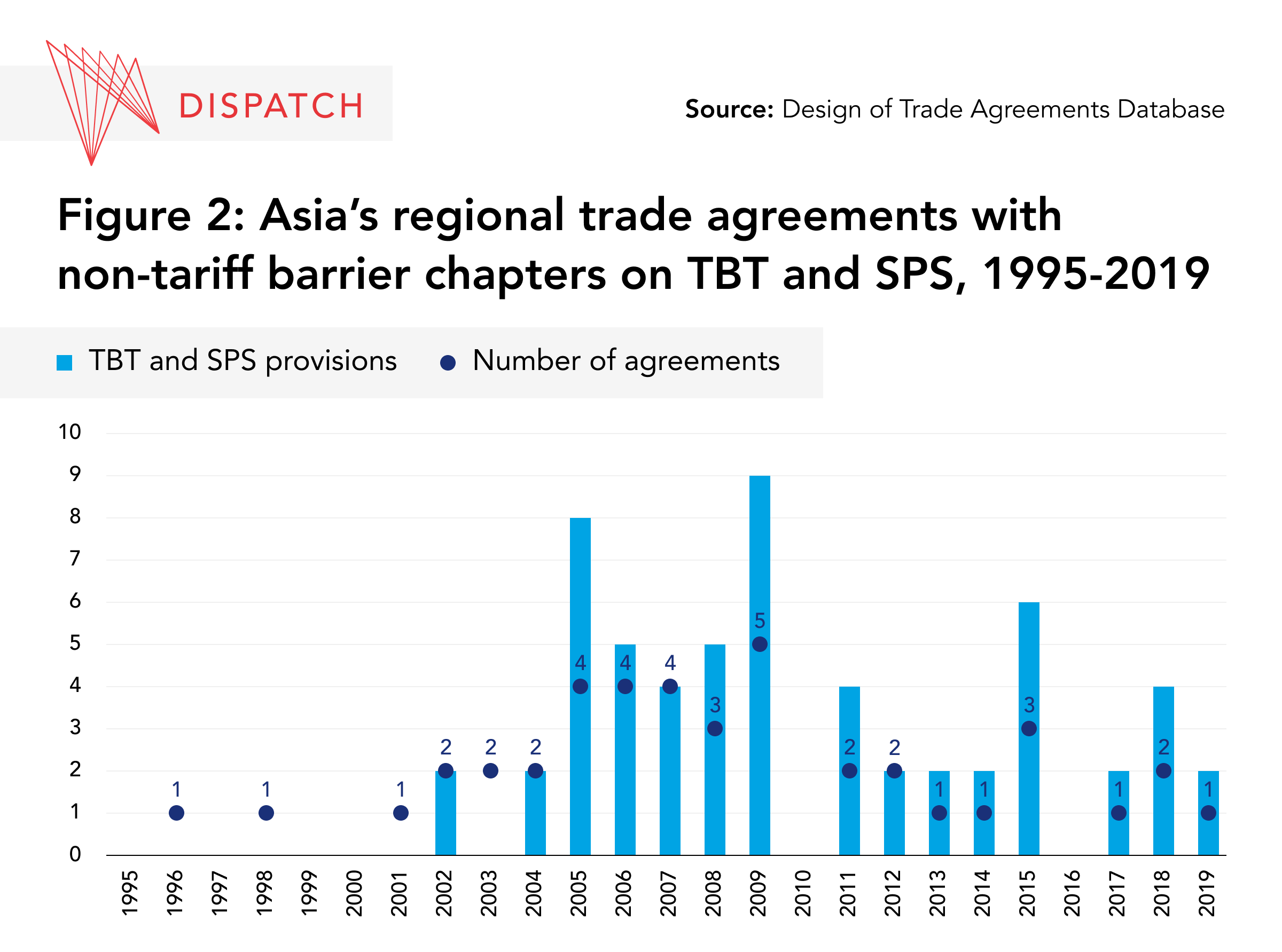

Bilateral and multilateral FTAs in the Asia Pacific are designed to lower tariffs and reduce NTBs. Early efforts to limit and standardize NTB measures began with the Asia-Pacific Trade Agreement (previously the Bangkok Agreement), signed in 1975. This agreement between Bangladesh, China, India, Laos, Mongolia[1], the Republic of Korea and Sri Lanka was the first FTA in Asia to contain provisions aimed at lowering and harmonizing NTBs. It was reinforced by the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization in 1994 (WTO Agreement), which marked the first multilateral attempt to regulate NTBs by incorporating the Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement (TBT Agreement) and the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement) in the WTO Agreement’s annex materials. While more trade agreements in Asia have tried to harmonize regulations and dampen the effect of NTBs (Figure 2) since the signing of the WTO Agreement in 1994, NTBs remain an obstacle to trade and are addressed in several trade agreements, including the CPTPP.

In 2018, the CPTPP set a new standard for how FTAs in the Asia Pacific approach NTBs by establishing a global benchmark for limiting them. The CPTPP distinguishes itself from other trade agreements in that it establishes clear definitions and enforceable rules for NTBs beyond what is spelled out in the WTO Agreement. It includes chapters on technical and sanitary and phytosanitary barriers related to market authorization (i.e. authorization to market and sell products that adhere to the health and safety requirements of a given country), labelling requirements (e.g. language and nutritional labelling requirements), and certification requirements (e.g. product testing requirements or certification of origin). Under the CPTPP, 57 per cent of sanitary/phytosanitary and 66 per cent of technical barrier provisions are legally enforceable with NTB chapters harmonizing measures, ultimately reducing the cost of compliance and, subsequently, lowering the cost of goods.

Canada’s attempts to reduce NTBs in the region predate the CPTPP. The Canada-South Korea FTA (CKFTA), signed in 2014, was the first agreement Canada signed in the region to regulate NTBs. The CKFTA incorporated the key commitments of the WTO Agreement but went further by providing clear and enforceable rules. The CFKTA promotes the use of internationally accepted standards where possible (e.g. standardization of forestry products), promotes regulatory transparency, and includes a dispute resolution mechanism. The agreement still allows parties to adopt measures necessary to protect health and safety while ensuring that these measures do not significantly interfere with trade.

Lessons Learned from the Region

Canada is no stranger to NTB regulations, as evidenced by the CKFTA and CPTPP. Nonetheless, Ottawa can still learn from the experiences of its trade partners in the Asia Pacific. For example, in 2017, Australia released a Foreign Policy White Paper that identified NTBs as one of the primary problems faced by Australian businesses. Since then, it has taken significant steps to remove these barriers. In December 2018, Canberra released an action plan to reduce unjustifiable trade restrictions. The plan presents a three-pronged approach: improving access by making it easier for Australian businesses to report and overcome NTBs; increasing collaboration between government and businesses to quickly identify issues and address them; and improving transparency so that responsibilities, processes, and expectations are explicitly defined and easily understood. The Australian government has promised concrete action items to achieve each of the goals laid out in the plan. For example, it created a new online gateway for businesses to quickly and easily report their trade barrier concerns. So far, the plan has been largely well-received by certain sectors, such as the farming sector.

ASEAN economies also offer insights into best practices for NTB reduction. Reducing NTBs has long been a priority for these economies, with the 2009 ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement devoting an entire chapter to non-tariff measures between ASEAN member economies. Since then, the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) has committed to further reducing the costs associated with NTBs through the AEC Blueprint 2025. The blueprint prioritizes many of the same elements as the Australian action plan, namely, targeting the elimination of NTBs with the help of the private sectors. While Australia’s strategy is focused on the NTBs impacting Australia’s exports, ASEAN’s AEC Blueprint emphasizes the importance of standards harmonization in the AEC and aims to eliminate all NTBs among ASEAN economies.

Current Agreements Being Negotiated

Ottawa is in the process of negotiating two trade agreements with Asia Pacific economies: the Canada-ASEAN FTA and the Canada-Indonesia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (Canada-Indonesia CEPA), both of which will work toward minimizing and/or harmonizing NTBs. While the Canada-India Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (Canada-India CEPA) is currently paused, NTB discussions would have been an important element of the CEPA.

An FTA with ASEAN will support Canadian exporters trying to navigate an increasingly protected local market. ASEAN saw a 60 per cent rise in NTBs from 2015 to 2021, mainly in technical and sanitary and phytosanitary areas. For instance, the automotive sectors in many ASEAN member economies tend to be subject to quotas and licensing, complex conformity assessment procedures, national standards, high taxation regimes, and discriminatory policies favouring local manufacturers. These types of barriers can be resolved during the Canada-ASEAN FTA negotiations by harmonizing regulations and standards and recognizing assessment procedures.

Similarly, a trade agreement with India, if negotiations do resume, can help resolve long-standing trade issues related to NTBs. Since 2018, India has imposed quantitative restrictions on the import of peas to increase self-sufficiency and support Indian farmers. These are legitimate concerns and essential elements of India’s food security, but such restrictive measures also negatively affect the Canadian pulse industry, as India is the fourth-largest destination for Canadian pulses. Although India temporarily revoked the restriction in September 2021, Canada is seeking more predictability and longer-term commitment for pulse products in the Canada-India Early Progress Trade Agreement.

Likewise, the Canada-Indonesia CEPA can help eliminate NTBs that have impacted Canadian exports across various industries. For instance, in 2020, Indonesia enacted an import ban on sugar to protect the domestic market and increase domestic production, as sugar is considered a sensitive industry in Indonesia. At the same time, some NTBs may not be easily harmonized, and will require exporters to meet certain regulatory measures. For example, Jakarta’s newly proposed halal certification for most food and beverage products, going into effect in October 2024, will require Canadian exporters to adapt to comply with the new regulations. To support these exporters, Ottawa must equip Canadian traders with the guidelines and support they need to get certified.

Conclusion

Trade restrictions, in the form of NTBs, increase the costs of trade and lead to trade frictions among countries, making it imperative for countries to sign trade agreements that take NTBs into account. Canada’s Trade Gateway, a trade and investment promotion mechanism committed to in the Indo-Pacific Strategy, encourages Canadian businesses to expand their presence in Southeast Asia.

To help these businesses capitalize on the region’s trade opportunities, the Canadian government should continue providing tools and resources to help companies understand regional barriers to trade and setting up trade infrastructure in the form of trade agreements to mitigate tariff and non-tariff barriers to entry.

[1] Mongolia was accepted to APTA in September 2020.