In June 2018, APF Canada, in partnership with Global Affairs Canada’s International Education Division, convened a series of roundtable discussions on how to help more Canadian youth and young professionals connect with China-related networks and careers, and how to support them in having meaningful experiences learning about and engaging China. This blog is the first in a series in which we dig deeper into some of the valuable programs and program ideas that surfaced during these discussions. A link to a report on the roundtable discussions can be found here.

Canada-China relations are fragile at the moment but episodes like the one we’re in now are precisely when we need to remind ourselves that China is more than the actions of its government. While government-level tensions are extremely important, the relationship also comprises thousands and thousands of personal ties based on friendship, shared research interests, or a common passion for art, education, or the environment, that binds us together as people.

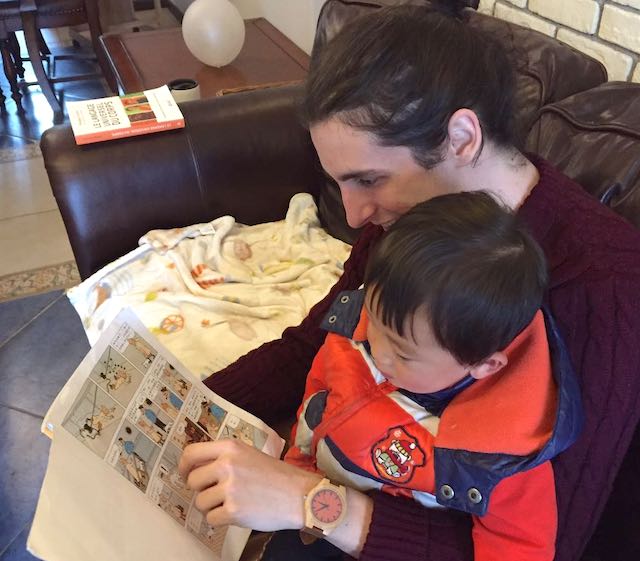

Alexandre Gosselin with host family

This kind of one-on-one familiarity across cultures will become ever more vital to Canada as China continues to grow. And as we have written elsewhere, it is particularly vital that this connectivity is encouraged and supported among Canadian youth to help them develop the types of China competencies that will be valuable to their future careers. An effective but largely underutilized means for building these people-to-people ties is ‘outbound mobility’ programs – study abroad, internships, and exchange programs. Ideally, these programs would include a homestay component, a portion of the time when a student lives in a Chinese home and has the opportunity to interact regularly and in an informal setting.

One such program is the Canada-China Young Leaders Program (CCYLP). It was launched in 2017 by Canada World Youth (CWY), an important player in Canada’s cultural exchange landscape dating back to 1971. What makes this program unique is that it includes a one-month homestay and opportunities to volunteer. Why does this matter? According to Mike Power, CWY’s Vice-President of Programming and Operations, “a homestay experience is advantageous because it leads to intercultural sensitivity. Valuable interaction and nuanced dialogue take place in a home environment that may not necessarily happen in a classroom, workplace, or other situation.” In other words, the arrangement allows for extended, authentic interaction that may be difficult to experience in other more formal or more scripted environments.

An Up-close Look at the Canada-China Young Leaders Program

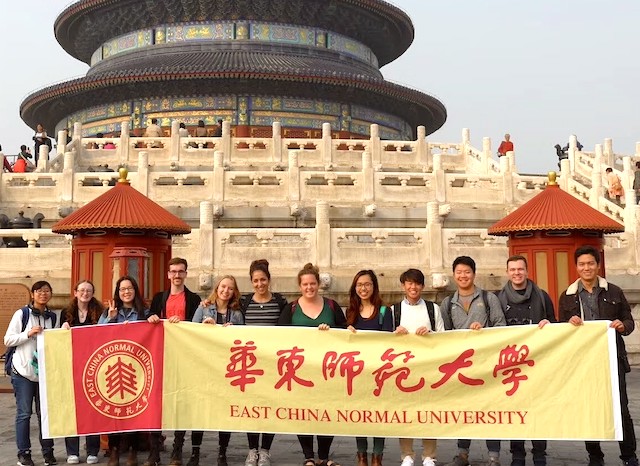

CCYLP students begin their program with a three-month academic term at East China Normal University (ECNU) in the large, cosmopolitan city of Shanghai. While there, they develop their Chinese language skills and learn about Chinese history, economics, politics, and society, all part of ECNU’s Global China Program. Students also use this time to acclimate to living in China. After the academic term concludes, they spend their final month in the southwestern city of Chongqing (population 33 million), where each participant is paired with a local host family. During the day, they volunteer as English-language tutors at Southwest University.

Canada World Youth crew in Beijing

Getting a window into Chinese family life: Vita Sackville-Hii, a 2018 CCYLP participant, said of her homestay experience, “What I enjoyed most was just seeing a [Chinese] family at home, engaging in day-to-day life.” A highlight of her experience was when her host mother’s parents came from their village to visit the family. Vita and the host grandfather, who could speak English, spent time together watching TV. Vita said she learned a lot from his commentary on the news. “We tend to think that Chinese people are very sheltered in their worldview,” she said. “But my conversations with my host grandfather indicated that was not the case at all.” She found that was also the case when they had frank discussions about the challenges China is facing, and what a Chinese perspective on those challenges might look like.

Alexandra Koslock at The Great Wall of China

Doing a first-hand comparison of education systems: Another 2018 participant, Alexandre Gosselin, said his area of study – political science and international relations – was a motivating factor in deciding to take a first trip to China. He valued the time in Shanghai, but also agreed that the homestay was the most beneficial aspect of the program because it allowed for “dialogues and honest conversation.” In addition to his interest in politics, he wanted to learn about different styles of education. His homestay gave him an up-close view. Alexandre is a Francophone from Sherbrooke, Quebec, and he exchanged ideas and observations on how English is taught in Canada versus China with his host mother, who is an English-language instructor. In addition, he got to observe the education ecosystem for Chinese children, including his six-year-old host brother (whom Alexandre described as “very cute”). He saw that young students do have a more open and carefree childhood before they have to make the “reality switch” to the highly competitive environment when preparing for the gaokao (high-school entrance exam).

Alexandre Gosselin with host brother

Feeling welcomed in a new home and city: For Alexandra Koslock, from the University of Winnipeg, one of the most challenging aspects of the homestay was having to speak Chinese with her host family. She was grateful, however, that the experience pushed her to work hard at using the Mandarin she’d studied while in Shanghai. In addition, she said, “I loved that I got to be part of a family dynamic that was different from my own.” Alexandra had previous homestay experiences in Halifax and Indonesia. She explained that host families generally really want to be part of the cultural interaction that is at the core of a homestay experience. Her Chinese host family was no different; to show her how much they welcomed her, her host sister gave up her bedroom for Alexandra, and the family took her to visit beautiful local spots that she would have never found on her own.

Alexandra Koslock with host mother

Connecting with and learning from peers: The other dimension of students’ time in Chongqing is serving as volunteer English-language tutors at Southwest University. This often allowed for opportunities not only to learn about China, but also to teach their peers about Canada. Vita explained that their teaching role took place over the Christmas holiday. Some of the Chinese students asked her about the meaning and history of that holiday. “I was reminded of the fact that Christmas is not celebrated everywhere, and having to explain it gave me a new perspective on the roots of my own cultural customs,” she said. “Including the commercial and spiritual meanings behind Christmas.” Afterward, the students began to relate it to their own holidays, which was a learning opportunity for her. And for his part, Alexandre said he had the opportunity to work with Southwest University’s Model United Nations Club, drawing on his own experience working in the Model UN world at Université de Sherbrooke.

Vita Sackville-Hii’s English-language students in Chongqing

Vita and Alexandre are also thinking about how China could become part of their graduate school or future career plans. And all were emphatic in saying that the homestay and volunteer service were a big highlight of their experiences and strongly encouraged others to consider the CCYLP to get good insights into what China and Chinese people are like at an on-the-ground and more intimate level.

An Opportunity for a Deeper Cross-cultural Experience

Students interested in applying for the China-Canada Young Leaders Program should submit their applications by February 10, 2020. Candidates must be between the age of 18 and 35 and must have completed two years of undergraduate study. Prospective applicants should also have a motivation to study Mandarin, learn about Chinese culture, and have an interest serving as an English tutor for the community service portion of the program, although no formal teaching experience is required.

If you are interested in studying in an immersion experience in China, visit Canada World Youth’s website and learn more about Canada-China Young Leaders Program.