Japan’s future is uncertain. The country has the world’s third-largest economy, yet this may change over the next few decades as its population—the fastest aging in the world—plummets from 126 million in 2015 to 87 million in 2060. On top of this, Japan’s Health and Welfare Ministry estimates that by 2060, the number of elderly aged 65 and older will account for 40 per cent of the population. As well, the low birth rate of 1.42 children born per woman is among the lowest in the world. These numbers, along with a shrinking workforce, are positioning Japan in the midst of a looming demographic crisis.

Current Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has placed these demographic challenges high on his list of priorities, and as a solution, suggested increasing the number of women entering the workforce and setting up more programs to help boost the birth rate. Commentators have voiced that this is not enough to maintain Japan’s economic prowess. Another option that has been considered, but not put into force, is the opening up of Japan’s doors to more immigrants. Hidenori Sakanaka, a former Justice Ministry official and director of the Tokyo Immigration Bureau, is a fervent supporter of this option and proposes 10 million migrants be accepted over 50 years to avoid the negative consequences of a declining population and shrinking workforce.

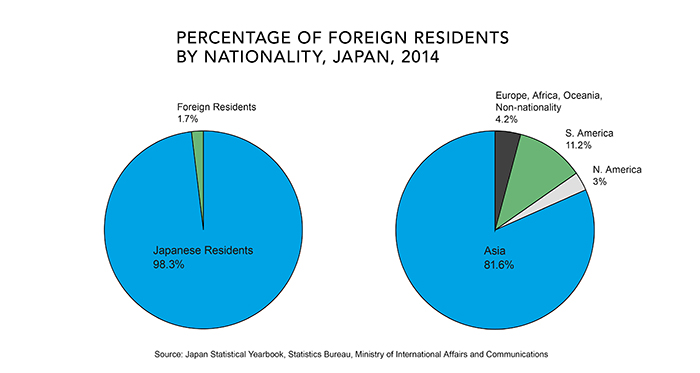

For Japan though, an influx of migrants will not come with a snap of the fingers. Japan is a relatively homogeneous society, with less than two per cent of the population considered as non-Japanese—mostly comprised of Chinese and Koreans. As such, preserving Japanese culture, language, and society has greatly influenced Japan’s immigration policies. Although these policies draw heavy criticism from immigration supporters and other industrialized countries for being strict and rigid, the policies have transformed along with Japan’s post-war immigration history.

For Japan though, an influx of migrants will not come with a snap of the fingers. Japan is a relatively homogeneous society, with less than two per cent of the population considered as non-Japanese—mostly comprised of Chinese and Koreans. As such, preserving Japanese culture, language, and society has greatly influenced Japan’s immigration policies. Although these policies draw heavy criticism from immigration supporters and other industrialized countries for being strict and rigid, the policies have transformed along with Japan’s post-war immigration history.

Japan’s Immigration Control Law, which was enacted in 1952 to control immigration into the country, was modelled on the U.S. system. Even so, this law did not encourage immigrants to settle in the country, nor did it consider them as members of Japanese society. After Japan’s mid-1980s economic boom, the number of foreign migrant workers, mostly from developing countries in East and Southeast Asia, grew in the late 1980s, causing the Immigration Control Law to be reformed to facilitate the immigration of professional and skilled personnel. This laxer outlook on immigration, primarily to fill labour market gaps, caused more programs to be made available to help over 75,000 unskilled labourers find job opportunities in Japan. As well, Nikkeijin (descendants of Japanese emigrants) were offered residential status regardless of occupation, causing an influx of Japanese Brazilians. As a result, the ‘Brazilian’ population in Japan grew almost six-fold from 56,000 in 1990 to over 286,000 in 2004.

Public opinion has also played a role in shaping immigration policy in Japan. Public opinion polls show that the Japanese public is not fully ready to accept a large number of immigrants, with one opinion poll showing that at least half the population is opposed to the increasing presence of foreigners in Japan. There is also a growing perception that migrants, especially illegal ones, are contributing to the rising crime rate and general deterioration of public security. This perception led to the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act being amended in 2004 to help cut the number of unauthorized foreign residents, then estimated at around 250,000.

Since half a decade ago, Japan has seemed more willing to open up its borders to immigrants, but primarily with the aim of dealing with labour shortages. For example, in 2012, Japan hoped to attract more highly skilled foreign workers through its new point-based system, which follows the examples of Canada and other countries by rating each immigrant based on different criteria. The original target was 2,000 applicants per year, but only a quarter of this number applied. As well, in 2010, Japan was the first Asian country to join the United Nation’s third-country resettlement program for refugees. Each year since then, the government has accepted Karen refugees along the Thai-Myanmar border interested in resettling in Japan, although the program has been criticized for not attracting the interest of enough refugees and for not helping enough in the assimilation process. In addition, just recently Prime Minister Abe’s ruling party announced it is considering policies to speed up the number of temporary foreign workers coming into Japan. One of the options proposed is establishing a guest-worker program that will extend work visas for industries facing labour shortages from three-year visas to five-year visas.

These days, Japanese immigration policy seems to be at a crossroads. Demographic and economic factors are driving Japan to embrace a more open immigration policy, while history, society, and public opinion are prompting the country to adopt stricter immigration controls. Over the past half a decade, initiatives put out by the government suggest that the prospect of Japan moving toward a more open immigration policy may be viable in the coming years. But if this does happen, would it be to the extent needed to counter a declining population and shrinking workforce?

To explore other posts in our Migration Matters series, please click on the links below:

Migration Matters: Project Overview

Migration Matters: Malaysia