This year marks the 40th anniversary of Canada’s relations with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). ASEAN is a regional organization that comprises 10 Southeast Asian countries and promotes economic growth, peace and security, and collaboration and assistance on matters of common interest to the region. To mark Canada’s anniversary with the organization, His Excellency Le Luong Minh, the secretary general of ASEAN, visited Canada, with stops in Ottawa and Vancouver.

Speaking to staff of the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada), the secretary general stated that ASEAN-Canada relations had “never been stronger,” but also discussed ways to further deepen ties by engaging with the ASEAN Community’s three pillars: the ASEAN Political-Security Community, the ASEAN Economic Community, and the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community.

Given that Canada is focused primarily on issues that lie within the purview of the ASEAN Economic Community, and considering that developments within this sphere are slow moving, it is worth considering the secretary general’s advice for Canada to further engage with work that fits within the other two pillars to strengthen the foundation for future Canada-ASEAN relations. That being so, why is it necessary to diversify Canada’s relationship with ASEAN beyond economics, and how should Canada invest in the other two pillars?

Strengthening Canada’s Relationship with ASEAN

Currently, Canada’s ties with ASEAN are mainly focused on developing economic connections. For example, in August 2016, Canada’s international trade minister announced that Canada would begin plans for a feasibility study on a Canada-ASEAN free trade agreement (FTA). As part of this, APF Canada and partners recently released an economic opportunity study on the potential FTA. It showed that two-way trade flows under an agreement could expand by C$4.8B – with the potential to reach as high as C$10.9B – in the first 10 years. In short, there are convincing reasons why establishing an FTA with ASEAN, and focusing on the economics of the relationship, makes sense for Canada.

But there are some practical limitations to this approach. First, the process toward finalizing an FTA with ASEAN will involve several steps, each requiring significant time commitments. Second, Canada has limited capacity to deal with multiple trade agreements at any given time. This means that Canada needs to prioritize its engagement. In the near term, Canada will be preoccupied with renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), working toward an FTA with China, and then working with the TPP11 (the 11 Trans-Pacific Partnership signatories remaining after the United States’ withdrawal from the agreement). With these other FTAs in the foreground, an agreement with ASEAN may take a backseat. Along with this, pundits in Asia have criticized Canada for being opportunistic in Asia by focusing too narrowly on economics and trade.

That being so, Canada could continue to bolster its ties with ASEAN in other arenas that would help keep the region on the minds of Canadians and perhaps aid, even if indirectly, in the advancement toward a future FTA

ASEAN Community Pillars

ASEAN created the ASEAN Community, composed of three pillars it felt were most important for building an integrated regional community. The first pillar is the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC). Formally established in 2015, the AEC is working to create a single regional market integrated with the global economy. If taken collectively, ASEAN has the seventh-largest economy in the world and includes three of the world’s 10 fastest-growing economies by gross domestic product. It is within the second two pillars, however, that Canada can diversify its relations in the region: the Political-Security Community and the Socio-Cultural Community.

Canada could further build on cultural and people-to-people relationships by boosting engagement with the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community priority areas, which include human development; building cultural identity; ensuring environmental sustainability; and social welfare and justice.

Canada is well positioned to support ASEAN on a number of these fronts. Canada has a wealth of information on addressing environmental sustainability, social welfare, and social justice, and diaspora linkages across borders can help circulate more of that information into Southeast Asia. For example, the Philippines, a member of ASEAN, has been one of Canada’s largest sources of immigrants over the past decade. In 2016 alone, Canada welcomed nearly 42,000 permanent residents from the Philippines.[1] In addition, almost one million Canadians cite various ASEAN country ethnicities as their ethnic origin.[2] With the large Southeast Asian diaspora community in Canada, there is significant opportunity to exchange cultural knowledge between the two regions, and also among Canadians. According to APF Canada’s 2016 National Opinion Poll, when asked to rank feelings of favourability toward places in Asia, Canadians tend to have just lukewarm feelings toward ASEAN. Canada could further leverage diaspora communities to help increase the broader Canadian public’s awareness of Southeast Asian culture.

Education is another avenue by which Canada could increase socio-cultural ties with ASEAN and support human development. A growing middle class across ASEAN member states means that the number of youth in the region pursuing higher education is increasing; many of these students are looking for options to study abroad. For example, the number of international students in Canada from Vietnam has already increased over 400% since 2000.[3] Education exchange should work both ways, with ASEAN students coming to Canada and Canadian students studying in Asia. More students coming from ASEAN countries will help Canadian students develop ties to the region, and Canadian students abroad can develop international networks and a global mindset as well as promote Canada. While there are currently some initiatives to bring students from certain ASEAN countries into Canada, there are almost no Canadian students moving the other way.

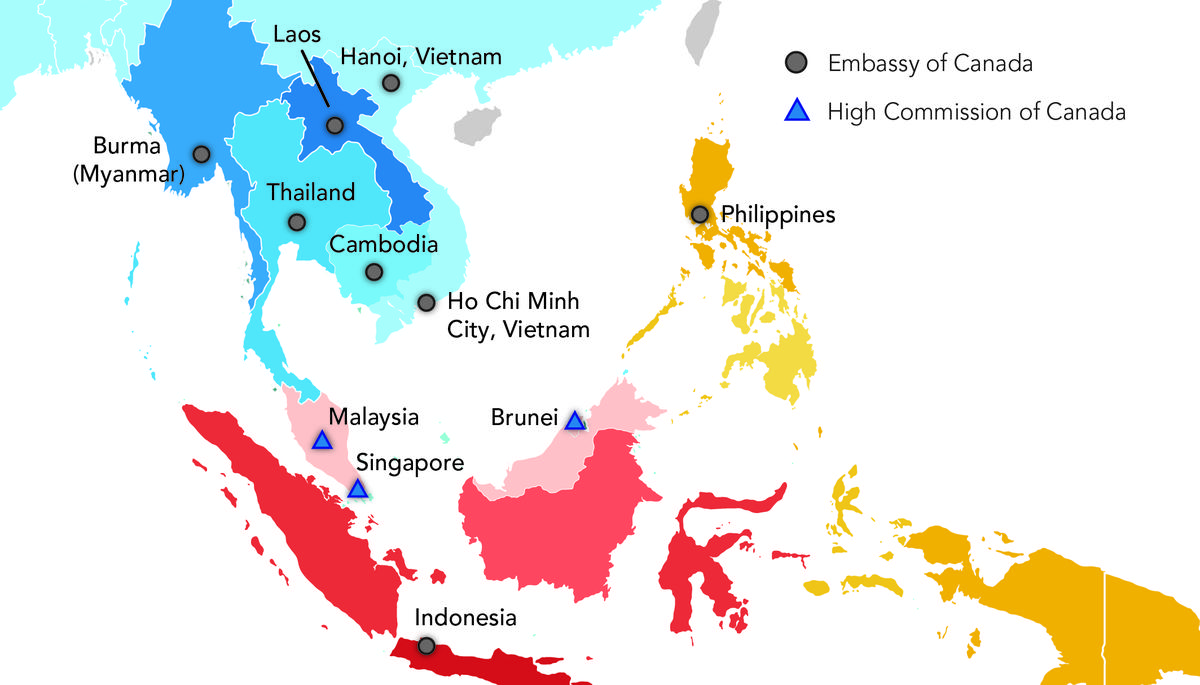

The final pillar is the ASEAN Political-Security Community, which enhances political stability, good governance, and human safety and security, and has been credited with strengthening peace and stability across the Asia Pacific. Canada has a foot in the door through membership in the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific and the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), two forums for dialogue on Asia Pacific security between ASEAN and non-ASEAN members. Within the ARF, Canada has engaged on a number of security threats and challenges facing the region. These efforts include funding projects such as: training first responders in Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines on chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear incident response; a disaster risk management program in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam; and a container control program in Myanmar that bolsters the customs capacity of the local ports to fight against trafficking of illicit goods in sea containers.

These types of engagement are a good start, but more is needed. Canada has goodwill in the region but lacks a sustained presence. The gap between goodwill and being present shows that there are still a number of key ASEAN security institutions that Canada is not a part of; Canada is ASEAN’s only dialogue partner not invited to be a part of the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting Plus, and Canada was flatly denied a seat at the East Asia Summit when it requested one in 2012. Canada needs to show it is truly committed to the region’s security in order to be accepted by these institutions. By joining these other forums, Canada would gain better insight on issues being debated in ASEAN and would build further credibility and influence.

Going Forward

In the past, Canada has lacked consistent economic, political-security, and socio-cultural engagement in ASEAN, and it has been noticed – to the detriment of Canada’s current ambitions in the region. The Canadian government has recognized the 40th anniversary of its relations with ASEAN as an opportunity to begin a new chapter in the economic relationship. While Canada has started the process for an FTA, that process could take a long time. Between now and when Canada negotiates an FTA with ASEAN, there is a window of opportunity for Canada to strengthen the relationship through other available avenues. Showing commitment on a number of fronts will both increase awareness of the relationship across ASEAN and Canada, and rebuild Canada’s reputation of being more than a fair weather friend.

[1] Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, Permanent Residents, February 2017.

[2] Statistics Canada 2011 National Household Survey, total generation status and both single and multiple ethnic origin responses

[3] Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, Temporary Residents, February 28, 2017.