On September 25, 2017, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe rolled the dice and called a general election on October 22, a full year ahead of schedule.

The election campaign was replete with drama. In the course of barely four weeks, years’ worth of political evolution took place on an extremely compressed scale and in a manner that would be inconceivable in many otherwise similar democracies. Several issues of relevance for Canada hung in the balance: the future of TPP-11 (CPTPP), Japan’s role in support of the global liberal order and Paris agreement on climate change, and Japan’s role in global security.

When the results were announced on the night of October 22, they were rife with paradox. Three core outcomes stand out.

First, Abe’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) smashed not one but two opposition parties. While the ruling LDP and its coalition ally, the Komeito, lost some seats, the ruling coalition retained its supermajority of two-thirds in the lower house (total of 313 seats out of 465, or 67% of seats).

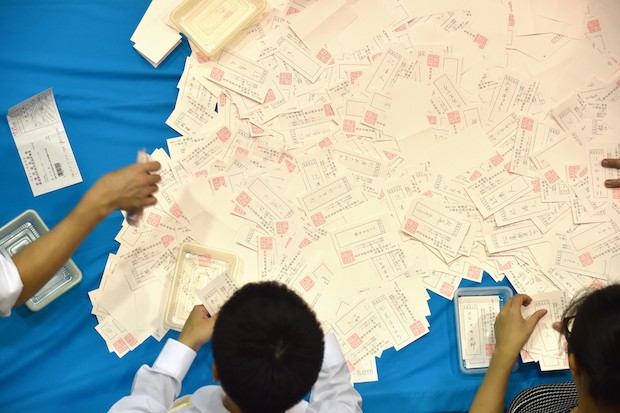

Officials of the election administration committee count ballot papers for Japan's general election at an election office in Tokyo on October 22, 2017. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe swept to a resounding victory, winning a mandate to harden his already hawkish stance on North Korea and re-energize the world's number-three economy. | Photo: Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty Images

Second, the opposition to the ruling LDP, while it has not lost strength, has experienced a complete structural transformation, which included the dissolution of one party, the creation of two new parties, and a new lead opposition party. For example:

- The DPJ, the major catchall opposition party, essentially dissolved on September 28, asking its elected MPs to rally behind the newly created Party of Hope. Key DPJ politicians and former leaders ended up running as independent candidates.

- The Party of Hope, a pro-reform party with hawkish views on security and constitutional change, led by a charismatic and ambitious female politician, Yuriko Koike (the governor of Tokyo), was created on September 25. Koike became a threat to Prime Minister Abe within days, only to gradually decline in importance two weeks later after refusing to run for a seat herself (and to resign the Tokyo governorship). The party ended up winning 50 seats.

- A new leftist party, the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP), was created on October 2, under Yukio Edano, after Koike refused to accept some former DPJ members under her banner. The Japan Communist Party (JCP) entered into an alliance with the CDP, the first JCP alliance in recent Japanese politics. The result was that the CDP surged from 15 incumbents to 55 seats, becoming the lead opposition party. However, without reforms within the JCP, this new CDP-JCP cluster may be pushed too far to the left to be able to become a mainstream governing party.

Third, for all the appearance of a landslide for Abe and the LDP, Abe’s victory is weakened by three flaws. First, turnout was extremely low (53.68%). Second, Cabinet approval was very low for such a victory: with only 51% approval (37% disapproval). Third, exit polls showed that a majority of voters (51%) did not trust Prime Minister Abe. There is no majority support for Abe’s pet commitment to reforming the constitution (especially Article 9, the so-called war-renunciation article, which officially prohibits Japan from maintaining an army).

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe answers questions during a press conference at his official residence in Tokyo on November 1, 2017. Japan's parliament on November 1 formally re-elected Shinzo Abe as prime minister after his party's crushing election victory, setting the 63-year-old on track to become the country's longest-serving premier. | Photo: Toru Yamanaka/AFP/Getty Images

Despite this lack of love or trust by a majority of voters, Abe has played by the rules of the political system with tactical brilliance and won solid power for the next four years. In policy and geopolitical terms, this is what will matter. Politically, however, as noted by Japan analyst Tobias Harris, Abe may have hastened a critical realignment of the party system and helped midwife a more coherent left-of-centre opposition (under the CDP) that may become more effective in the coming years, especially given its savvy use of social media and urban youth mobilization.

In the short term, what does the election mean for international partners such as Canada? First, Japan will continue its unusually long spell of stable conservative governance, gradual economic reforms, support for advances in the global trading order, and assertive foreign policy in Asia and beyond. In other words, steady as she goes. Diplomats, businesspeople, and partners can breathe a sigh of relief. Second, with all main parties supporting international trade, the global institutional order, and pro-climate policies, there is clearly no constituency for a Trump-like populist movement in Japan. Naturally, the near absence of immigration robs such political entrepreneurs of an anti-immigrant platform. But the key point is that voters see hope in economic and social reforms, support climate change mitigation policies, and are anchored in an internationalist consensus. However, one variable remains a potential spoiler for future development: Japan faces very real and worrying security threats from belligerent North Korea, rising China, and unpredictable America. These threats have not yet triggered support for a much more robust security approach and constitutional change, despite Abe’s efforts. But the potential is there.

Background to the Election — a Few Notable Features

Initially, the political context for Prime Minister Abe did not look very good. Because of voter fatigue with political scandals and of the controversial anti-conspiracy bill (which, among other things, punishes the sharing of information deemed sensitive with the media), support for the Abe cabinet was sliding throughout 2017, reaching an average low of 33%-34% in the summer. In July, Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike consolidated her image as the main nemesis of Prime Minister Abe when her party, Tomin First No Kai (Tokyoites First) won the Tokyo Assembly elections, building on her anti-LDP victory of 2016. Koike served as national security adviser to Abe in his first run as prime minister in 2006-2007 but later left the LDP and developed her own platform and image. She continued to support a hawkish approach on security matters and to support constitutional change, but developed a people-first approach and great responsiveness on daily life issues of economy, society, and environment. In 2017, her fame rose from her robust approach to the scandal related to the relocation of the Tsukiji fish market to make way for Olympic game developments to a site that was not environmentally sound. As of early August, Abe was potentially facing his last year in office.

Abe took action on August 3 with a smart cabinet reshuffle that brought in new energy, especially a new foreign minister and a new minister for internal affairs and communications. The gambit worked. By the end of August, support for the Abe cabinet was gaining strength. By early September, with a bit more steam on Abe’s side, he saw the opening for a snap election. The opposition, DPJ, was reeling with extremely low support under the transition from the outgoing leader to the newly elected leader, and Koike had not had time to organize on the national scene. Ever the gambler and eager to secure a stable political window through the G20 presidency of 2019 and the Olympic Games of 2020, Abe made his move and cleaned the slate.

On the economic front, Abe also benefited from positive news. On September 19, the International Monetary Fund published the latest World Economic Outlook forecast, upgrading its numbers for Japanese growth in 2017 from 1.2% to 1.5%. It also upgraded the estimate for 2018 from 0.6% to 0.7%, reflecting stronger consumption and new gains in the inflation rate. At the end of September, the Nikkei stock index had passed 20,000, a historic high since the bubble crash in 1990. At the same time, the economic outlook going forward is much less good and will be an immediate challenge for Abe.

A pedestrian looks at a TV screen displaying a map of Japan and the Korean Peninsula in Tokyo on September 15, 2017, following a North Korean intermediate range ballistic missile test that passed over Japan. | Photo: Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty Images

On the security front, the Japanese public just went through some severe scares from July to September when North Korea tested long-distance intercontinental ballistic missiles over Japan. The test on September 16 triggered debates, since all Japanese citizens received SMS notices to duck and cover while the missile was flying over Hokkaido. This tense security situation allowed Prime Minister Abe to call the election on the basis of a real North Korean threat, for which he required a new and strong political mandate, as the only politician with the ability to protect Japan. Voters understood this message, but post-election polls show that the impact was actually limited, possibly because October was a quieter month.

On all fronts, political, economic, and security, Abe’s calculation was impeccable. He was able to count on several reinforcing factors to support his election gambit.

What Explains the Outcome?

It is important to state what did NOT explain this election outcome. First, as noted earlier and unlike former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi in 2005, the election was not the result of a high support rate for Abe himself or even trust in Abe or support for some of his pet policies (such as constitutional change). Abe won in spite of weak personal support and no support for constitutional change. The Nikkei opinion poll on the eve of October 22 showed that 51% of voters did not trust Abe, including 69% of independents. The Abe cabinet did not enjoy a large post-election bounce either. On November 3, the Nikkei ran the results of an opinion poll, revealing that 47% of voters would prefer a smaller majority for the ruling coalition, 32% thought it was just good, and 14% would support an even bigger majority.

Second, the election results were not an endorsement for specific policy outcomes or policy preferences. In the post-election analysis published by Yomiuri Shinbun, 10% of voters said they voted to support “policy achievements” and only 6% had “high expectations for Abe.” Rather, 44% said that the results were due to fragmentation of opposition parties, and 36% stated that “the ruling coalition was better than the alternative.”[1]

Third, it is important to avoid any general statements about Japan turning more nationalist or more hawkish. The election results are a translation of the mechanics of an incomplete domestic party politics under the current electoral systems, rather than a broad expression of a policy shift.

Instead, two sets of factors explain the election outcome. First, the results reflect a moment of transition in the formation of an opposition party to the LDP. The DPJ finally crumbled after remaining as a moribund catchall party holding together leftist politicians, liberal reformers, and a few conservatives since the early 2000s and especially since its disastrous spell in government from 2009 to 2012. The breadth of its policy spectrum and the hodgepodge of personalities and preferences in its midst made it an unlikely governing party. Yet institutional inertia made it stick around until now. September was the moment when a new set of parties appeared from its remains: one conservative populist party and one reformist pacifist party. The division, however, proved fatal in the short term, given the reality of the electoral system.

The second factor is the interaction of tactical moves by Abe and Koike in particular. Abe played his initially weak hand deftly and accelerated the political time to take advantage of the moment of transition and chaos in the opposition. It worked. As for Koike, she had a chance to emerge as the true opponent to Abe but made a series of bad moves that destroyed her chances. In particular, by refusing to stand as candidate for prime minister, she deflated the enthusiasm of her troops. By taking a hard line on new recruits from the DPJ, she appeared unnecessarily ruthless. In fact, her support even collapsed in the Tokyo PR block, i.e., on her home turf, because of her mistakes.

Impact on Party Politics

A woman shows an electoral leaflet of Tokyo Governor and leader of the Party of Hope Yuriko Koike during an election campaign in Saitama. Koike is a media-savvy veteran who charmed her way through Japan's male-dominated politics and transformed its sleepy political landscape with a wildcard new party that caught everyone off-guard. | Photo: Behrouz Mehri/AFP/Getty Images

The election has generated three interesting implications for party politics. First, predictably, the election has provoked a period of disarray in the opposition, especially the rump DPJ (which remains a key party in the upper house and must divide its assets and liabilities among the opposition). In the DPJ, then party leader Maehara immediately announced his resignation, leading to the election of a new party president. In the Party of Hope, Koike initially refused to resign, only to accept later the selection of a co-president, and eventually to accept responsibility and resign on November 14. Yuichiro Tamaki took over this fledgling party with a very uncertain future. In fact, after its flamboyant takeoff late September, the Party of Hope now garners only about 3% support. For its part, a better mood surrounds the CDP right now, as this party has gained a 17% support rate. But there is room for only one major opposition party to compete with the LDP under the current electoral system, and the landscape must sort itself out rapidly.

Yukio Edano, head of the new Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan, delivers a speech at an entrance of a train station during an election campaign appearance in Matsudo, Chiba prefecture October 11, 2017. | Photo: Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty Images

The second implication is the sudden appearance of a new and coherent party, the CDP, with the potential to consolidate itself into a credible alternative for power. For the first time, the policy preferences of this new party are quite tight and occupy the place on the party spectrum that is left empty by Abe. It is a party that has shown the ability to use social media and grassroots mobilization. It is in sync with the majority of the public on environmental and social issues. It has yet to develop a coherent economic and foreign policy platform, but the potential is there. Most interestingly, it is currently a potentially formidable force in the battle over constitutional revision, since the majority of the public appears to be closer to the CDP at the moment. As noted by Harris: “The CDP has a long way to go before voters will trust it with power, but there is at least some reason to hope for more vibrant political competition in Japan.”

The third implication is this important caveat. For now, the CDP has developed a tactical alliance (including electoral alliance) with the JCP. Without a change in the radical constitution of the JCP, that alliance would push the CDP too far to the left to be an electable governing party in the future.[2]

Impact on Abe’s Reform Agenda

In the short term, Abe’s victory yields precious political stability for his reform agenda and foreign policy, although he will have to face an upper house election in 2019. The election (coupled with the momentum from signing the TPP-11) should give more momentum to the prime minister to accelerate Abenomics reforms in corporate governance, agriculture, education, high tech, and green technology, even though the LDP has often acted as a brake on the efforts of his reformist lieutenants. In the short term, the economy is enjoying a spell of good growth (in the context of the post-1990 “lost decades”), and unemployment has fallen below 3%. But clouds could come quickly without further stimulus packages, giving an incentive to Abe to further delay fiscal consolidation. Recent data have shown that obstacles to innovation and attracting foreign talents remain extremely high. An acceleration of reforms in this area is necessary. One interesting promise made by Abe concerns free childcare, although the cost may be high.

The biggest domestic battle will relate to Abe’s cherished plan to reform Article 9 in the constitution. Such a reform would require a two-thirds majority vote in both houses of the Diet (which he controls), but also a 50% majority from the public in a national referendum. Currently, the public does not support the reform, and the battle will likely energize the CDP into the mother of all electoral battles. Should Abe try to take on this battle in 2018 or 2019 and lose, it would be hard for him to stay in power. Should he choose to wait until after the Olympic Games of 2020, he may run out of time. So the outlook is uncertain under current conditions. Only major security threats from North Korea or China could possibly lend the right momentum for Abe to achieve constitutional change.

Implications for Canada

In the wake of the election, what sort of partner can Japan be for Canada? There are three interesting areas for cooperation and engagement.

The first one is the newly signed TPP-11 (without the U.S.), now christened the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), where Japan and Canada are the two heavyweights. A bit of mystery continues to surround the November 11 meeting between Abe and Trudeau that led to a one-day delay in the agreement. However, the key point is that Canada and Japan now have a tool to advance some common rules in Asia and to increase bilateral trade. In the context of tough NAFTA renegotiations and uncertain Canada-China trade negotiations, the Canadian public appears particularly supportive of the TPP-11.

Japanese cast their ballots for Japan's general election at a polling station in Tokyo on October 22, 2017. | Photo: Behrouz Mehri/AFP/Getty Images

The second one is the larger potential cooperation over the future of the liberal order. In fact, Japan and Canada (along with Korea, Germany, and France) are probably the G20 countries now most committed to the support of an open, fair, and rule-based global order, which the US is now combating under President Trump. With the Japanese G20 presidency in 2019, there will be room for joint initiatives with like-minded countries such as Korea, France, and Germany. Similar joint efforts are possible on climate change. One potential challenge may be different views on how to deal with China. Canada or Europe may see China now as another key proponent of globalization, G20, or the Paris Agreement. Abe is less likely to let these issues trump his security concerns with China.

Finally, Abe has been keen to champion a new Indo-Pacific constellation of democracies with the US, India, and Australia, succeeding in nudging Trump to use the phrase. Canada may be able to engage on some issues with this new constellation.

Conclusion

The October 22 election was a brilliant tactical victory by Prime Minister Abe, giving him policy space and time to advance his economic reforms, including in domains of interest for Canada (agriculture, green technology, education, health) and especially in the context of the newly agreed TPP-11. Japan will be a valued partner for Canada in work on the future of the global liberal order, especially regarding trade, the G20, and climate change. But Japan and Canada are likely to continue to have differences of views regarding policy on China.

[1] Yomiuri polls, reported by Tobias Harris, Twitter account, October 24, 2017.

[2] I am grateful to Dr. Yosuke Sunahara for this point.