Canadians have watched from the sidelines as the crisis on the Korean Peninsula has spiralled upward, creating the greatest risk of the use of nuclear weapons since the Cuban missile crisis over 50 years ago.

That 1962 standoff was averted, at the brink, through cool-headed diplomacy and courage of leadership. It is the absence of such leadership, rhetorical restraint, and dialogue that makes the current situation so perilous. President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s trading of childish caricatures and insults has created an egoists’ standoff, fraught with the possibility of accidents and mistaken judgments triggering catastrophic results. The proverbial nuclear clock, as measured against North Korean provocative testing, is approaching midnight.

How to avoid missteps and establish a stable deterrent equilibrium among the key players, given the looming reality of a North Korean nuclear state, presents an enormous challenge. The risks of failure are extensive; the room for creative manoeuvre by Washington, Beijing, and Pyongyang is extremely narrow.

First steps must be taken, back channels explored, and two-step-forward-one-step-back frustrations managed. The scope for positive, proactive engagement by outsiders like Canada is very limited, but more feasible in the longer term through multilateral initiatives and people-to-people engagement. Should outright conflict break out, Canada, while an unlikely participant, will need to be prepared for massive humanitarian challenges in its aftermath.

A Nation Under Siege

“Objective” considerations aside, Pyongyang’s leaders believe that they have been under threat of elimination by the United States and its allies since their state’s emergence in 1948. The subsequent war experience, US troops in South Korea and Japan, Washington’s system of alliances, and the regular conduct of large-scale military exercises in South Korea all reinforce North Korea’s existential worries. No longer able to compete in conventional military terms, Pyongyang, for economic, strategic, and ideological reasons, views its survival contingent on attaining a second-strike nuclear capacity – i.e., the ability to attack if provoked and to respond if attacked against targets in and across the Pacific. Gadhafi’s fate and Saddam’s demise have reinforced this conviction, enhanced further by President Trump’s direct threats and ongoing campaign to revoke the Iran nuclear deal.

A North Korean Nuclear State … “on the cusp” (CIA Director Pompeo)

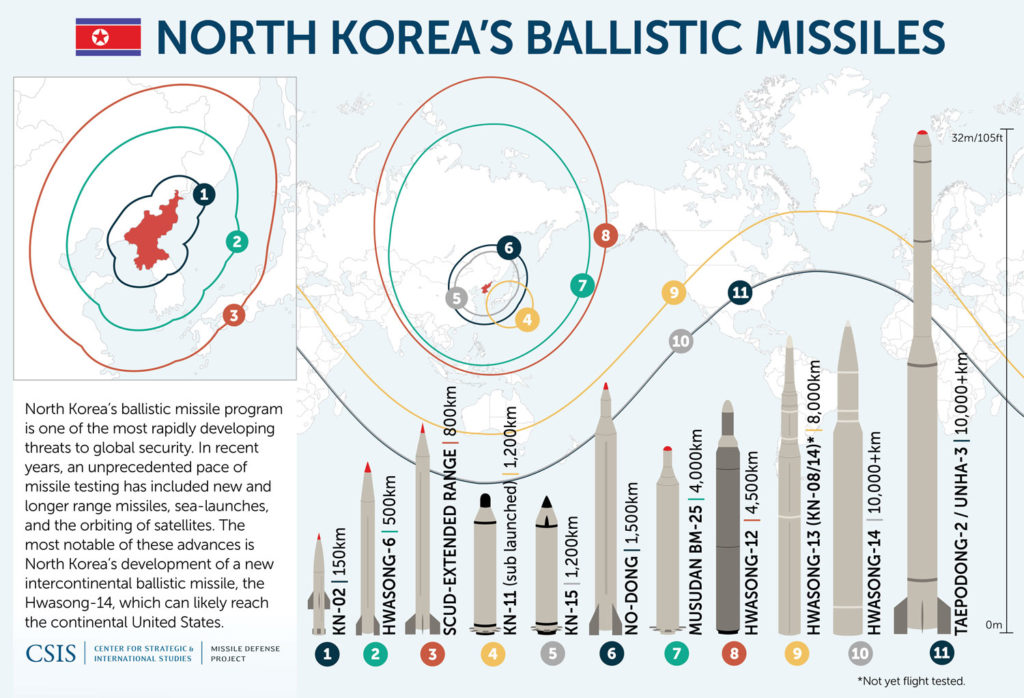

Pyongyang’s ambition to nuclear power status, germinated in the 1980s, culminated with Kim Jong Un’s 2016 declaration of North Korea as a “responsible nuclear weapons state.” This aspiration has moved with surprising rapidity toward reality during his leadership, with a race to complete and deploy a suite of missiles, including intermediate range and intercontinental ballistic missiles, along with the miniaturized nuclear warheads to arm them. In the aftermath of the 15 missile tests thus far in 2017, and September 2017’s nuclear weapon test (the sixth since 2006), the consensus is that North Korea will be able to attack targets in the continental United States within 6 to 12 months – some indeed claiming that Pyongyang is already there.[1]

Pyongyang has achieved what analysts term the “spectacular success” of its missile and nuclear programs through purported dealings with Egypt, China, India, Pakistan, Russia and Ukraine. Reverse engineering and sophisticated acquisition of dual-use technologies have given North Korea today an indigenous production capacity.

Rocketman vs. Dotard

Rhetorical posturing is an essential aspect of deterrent relationships, with the perverse rationality of “irrationality.” One has to appear willing to fulfil threats, despite any apparent logic of costs or capabilities. Kim and Trump are taking this “irrationality” to new extremes.

Whether or not Trump, with his antics, is putting up a smoke screen – i.e., advancing a purposeful strategy of sowing confusion, bewildering the North Koreans into thinking that he might well attack, and thus pushing them toward the negotiating table that the secretary of state has proffered – is frankly unknowable. The hope that that is the case has continually been eroded by Trump’s flailing tweets, impetuous decisions, and fomented dissent among his key advisers.

Photos: AFP/Getty Images

Little about Kim provides reassurance. His assessment that nuclear capability is his only assurance of regime survival, coupled with the state’s cultivation of his invincibility, and reinforced by his ruthless and immature personality, provide a frightening match-up with the US president.

From Extended to Direct Deterrence: A New Geopolitical Logic

With a North Korean nuclear state directly threatening the United States, the geopolitics of Northeast Asia have been transformed from an extended deterrence relationship, where the United States guaranteed Japan’s and South Korea’s security, to one of direct deterrence between the United States and North Korea, with Japan and South Korea now on the sidelines of a bilateral confrontation – Pyongyang having achieved its long-held desire for one-on-one dealings with the United States.

There is a concern that Washington may hesitate to deliver, given the continental vulnerability of its cities – naturally leading for calls for missile defences and military buildups in Japan and South Korea, with conservative opposition voices in both countries raising the prospect of attaining nuclear weapons.

A parallel concern is whether or not Kim Jong Un appreciates the calculus and consequences of his direct deterrence dealing with Washington. To date, he has been undaunted by the efforts of the international community and its key players, particularly the United States and China, to persuade or threaten to pre-empt or be “totally destroy[ed].” Furthermore, deeply ingrained North Korean mythology celebrates its historic “victories” over the United States with the full expectation of triumphing in any future conflict. While Kim Jong Un is not suicidal, his calculation of the Trump administration’s threshold of pre-emptive action may well be overly sanguine, especially in the context of further nuclear tests.

Foreign ministers from the U.S., China, Russia, and Japan meet at the UN Security Council in New York on September 21, 2017 to discuss the non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and press for sanctions against North Korea. Photo: Don Emmert/AFP/Getty Images

The ever-tightening regime of economic sanctions imposed through the UN Security Council and bilaterally by the United States and other countries has had little impact on the speed and success of North Korean nuclear and missile programs. The most recent sanctions, with bans on textile exports and significant cuts on oil imports, endorsed unanimously by the Council, are amplified by those announced by the United States that target individuals, banks, and corporations with dealings with North Korea. But again, these are expected to be only marginally effective, certainly in the short run. Their impact will be too late to alter the current nuclear advancement; their impact will be borne by the already stricken North Korean citizenry. The millenarian, ideological zeal will carry the Kim dynasty and its people through such severe privation.

Despite sanctions to date, North Korea’s economy is estimated to have grown by four to six per cent annually over the last three years due to increased economic autonomy, agricultural reforms and better weather conditions, favourable global market prices, and networks of lucrative, illicit activities. When taking over, Kim Jong Un boldly promised both nuclear weapons and economic reform, his byungjin policy – and to a notable degree, he has delivered. Analysts point to the growth of an urban “middle class,” composed of favoured members of the Workers’ Party and military, official, entrepreneurial, and technical elites. To thwart any mobilization of discontent, Kim has combined a “military first” policy of co-optation bolstered by the ruthless elimination of any suspicion of disloyalty, including by having his own half-brother assassinated.

The China Factor

China is critical to any effort to influence the North Korean regime. It continues to hold a virtual monopoly on North Korea’s official trade (roughly 90 per cent overall, in which oil imports and textile and coal exports play central roles), giving China a chokehold that could force a North Korean retreat, or at least a halt, on its nuclear path.

A truck loaded with goods makes its way across the Friendship Bridge from the Chinese border city of Dandong, in China's northeast Liaoning province, to the North Korean town of Sinuiju on September 4, 2017. Photo: Greg Baker/AFP/Getty Images

A truck loaded with goods makes its way across the Friendship Bridge from the Chinese border city of Dandong, in China's northeast Liaoning province, to the North Korean town of Sinuiju on September 4, 2017. Photo: Greg Baker/AFP/Getty Images

Beijing’s calculus, however, is a much more complex consideration of regional and global forces – its long-term, fundamental geostrategic interests are to sustain North Korea as a buffer zone, and if a united Korea, one denuclearized and without foreign troops. In the shorter term, it seeks to avoid conflict that would bring regime collapse and chaos, coupled with floods of refugees; to avoid being targeted by missiles (including North Korean) and missile defence systems; and to halt the ramping up of the US military presence in the region. Beijing and Pyongyang find themselves trapped in an unsatisfactory relationship – Kim viewing China as no longer a reliable ally, unwilling to guarantee his regime, and pushing too hard for internal reform; President Xi Jinping regarding Kim as recalcitrant, ungrateful, and bringing ever-greater security threats to China as the United States and its allies respond to Pyongyang’s military adventurism with increased regional deployments, including the Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) missile defence system.

Disaffection with North Korea’s refusal to halt its march to a nuclear state has resulted in Chinese policy redirections. Beijing now endorses the tightened, UN Security Council-authorized sanctions, and commits to clamping down harder on North Korea’s oil imports and key exports. These sanctions will bite Pyongyang harder. But the chances of the sanctions having the desired effect, as noted above, are modest. China will calibrate its economic and political relationship to keep the Kim dynasty on life support – and thus its nuclear weapons agenda along with it.

No Trump Card

Once in the White House, the dimensions of the North Korean conundrum hit home for Donald Trump with the realization that there is no silver-bullet solution. At times, near chaos has ensued. With senior political appointees and conservative figures repeating the hard line of their president, diplomacy and negotiation are spurned publicly and castigated as gestures of appeasement. While assuring the president that there are military options, senior generals and Department of Defense officials state privately and publicly that there are none that do not threaten to trigger the catastrophe of mass civilian casualties. Even Trump’s former chief strategist, Steve Bannon, the archetypical conservative, concurred “there is no military solution [to North Korea’s nuclear threats]” and, indeed, goes so far as to admit “they got us.”

US diplomats are beleaguered. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has been in an untenable position. On the one hand, his time is spent reassuring allies of US security guarantees, pushing China to clamp down further on North Korea, and stressing the administration’s adamant policy of denuclearization prior to any talks. On the other hand, and not unexpectedly (and despite his boss’s ridicule), he has explored various channels with Pyongyang, seeking communication, if not dialogue and negotiation. He has sought to dampen North Korean fears of the United States by committing to a policy of four noes: no regime change, no regime collapse, no accelerated reunification, and no sending forces north of the 38th parallel.

Perhaps initiatives are underway through Beijing, New York, Geneva, or Pyongyang itself to defuse the situation. Absent these and progress on them, there is little cause for optimism. Tillerson knows and warns that time is running out … with his eyes as much toward Washington as toward Pyongyang.

Coming to Terms … “diplomacy until the first bomb drops” (Rex Tillerson)

The hard reality is that avoiding war means a negotiated solution; a negotiated solution means compromises on all sides. To date, this prospect has been anathema to Washington and Pyongyang – the latter refusing to negotiate until recognized as a nuclear state, the former vowing that this can never happen. Avoiding disaster dictates that a conversation must begin.

A North Korean soldier walks near the Yalu river near Sinuiju, opposite the Chinese border city of Dandong, on April 16, 2017. Dandong city is the main crossing point to North Korea, and every day hundreds of tourists embark on small boats for a cruise on the Yalu border river and a fleeting glimpse of another world. Photo: Johannes Eisele/AFP/Getty Images

A North Korean soldier walks near the Yalu river near Sinuiju, opposite the Chinese border city of Dandong, on April 16, 2017. Dandong city is the main crossing point to North Korea, and every day hundreds of tourists embark on small boats for a cruise on the Yalu border river and a fleeting glimpse of another world. Photo: Johannes Eisele/AFP/Getty Images

Over the course of the last decade and a half, a spectrum of options to relieve tensions and achieve stability on the Peninsula have been attempted. Regional and international players have tried at both Track 1 (official) and Track 2 (unofficial) levels. China has become increasingly engaged in the aftermath of the failure of the Six-Party Talks, which ended in 2009. South Korea has oscillated between rigid hard-line and tentatively accommodative stances, its leadership stymied by Pyongyang’s actions and its own deep domestic divisions.

Prospects for US–North Korea relations were most favourable at the turn of the century, with the Clinton administration’s overtures to Pyongyang, highlighted by Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s visit to the North Korean capital. This avenue was abruptly dead-ended by newly elected President Bush’s inclusion of North Korea in his “axis of evil” – effectively forestalling any meaningful bilateral or multilateral initiatives for the last 15 years.

Where and how to begin? What policies and strategies might propel incremental, positive steps? Most options discussed converge around “pause for pause” or “freeze for freeze” or “double pause” rubrics, all referring to the two sides effectively “taking deep breaths” and, through increasingly regularized communication, softening the edges of their hard-line positions. It is a long way, however, to the oft-noted “pause for pause” that would involve North Korea halting its testing and the United States in turn halting military exercises and other “provocative” gestures. To date, direct bilateral feelers hinted at by both parties (in New York, Beijing, Pyongyang itself, and European cities) have been rebuffed publicly, but one must assume remain active. The EU and the select European states that operate embassies in Pyongyang have looked to opportunities to facilitate discussions, and will continue to do so.[2]

Intermediaries, however, are certain to be involved – in particular, China. How it leverages its influence on Washington and Pyongyang will be critical. Xi Jinping sees both his national interests and his reputation as a global power at stake, but has been preoccupied with solidifying his domestic hold on power for the just-concluded Party Congress.

The bottom line: There appears to be no avoidance of the acceptance, at present, of a nuclear-capable North Korea, however constrained; and many analysts, including previous hard-liners, are now coming to terms with this difficult reality. Living with the odious Kim regime will be politically and morally painful. If not managed carefully, it could bring great loss of face for the United States and for Trump personally – indeed, quite possibly too great a potential personal embarrassment for the volatile president to abide, triggering the real risk of a lashing-out that pushes all over the brink. On the other hand, a sword of Damocles hangs over Kim Jong Un. He sees his survival dependent on achieving nuclear power status, but can this be accomplished without provoking a conflict with the United States – bringing an assured end to his survival?

Canada–North Korea: “Controlled Engagement”

Ottawa’s historical credentials on the Peninsula are grounded in the Cold War, including its participation in the Korean War and subsequent UN engagement on the Peninsula.[3] With the end of the Cold War, Canada looked in the late 1990s to recognize North Korea; in 2001, it opened diplomatic relations, and this was preceded and followed by a series of low-key, but informative, Track 2, bilateral and multilateral engagements with North Korean participants. Kim Jong Il’s (the current leader’s father) missile development and pursuit of nuclear weapons, in the face of Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons pledges and UN resolutions, dictated little progress toward normalization. In 2010, Canada joined ranks in imposing what Prime Minister Stephen Harper characterized as “the toughest sanctions in the world,” as part of its policy of “controlled engagement.” This remains on the books today. Diplomatic relations with North Korea are curtailed. A Canadian ambassador has been unable to present his/her credentials. A limited number of visits by officials go on, with our interests being managed through the Swedish embassy in Pyongyang.

Key among Canada’s Track 2 initiatives that included North Korean participation was the North Pacific Cooperative Security Dialogue, funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade and run by an academic team at York University during the early 1990s. Subsequently, Canadians participated actively in the Council of Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific, the only inclusive, institutionalized, region-wide Track 2 institution for fostering co-operative security and dialogue, and one that North Korean representatives continue to attend.

The Trudeau government, in line with its overall attitude toward (re-) engagement of non-like-minded states, did encourage one-time Minister of Foreign Affairs Stéphane Dion to explore possibilities on the Peninsula. Our diplomatic tone did change somewhat in tune with Ottawa’s multilateral inclinations; condemnations of Pyongyang’s tests now have appended sentences encouraging dialogue as the only path to a long-term solution.

That limited lines of communication do remain open was apparent with the recent visit of a high-level, official delegation from Ottawa, headed by National Security Adviser Daniel Jean, to gain the return to Canada of imprisoned pastor Hyeon Soo Lim. While behind-the-scenes diplomacy had been ongoing, the timing is attributed to a decision at the highest levels in Pyongyang. Canadian officials deny or are silent as to any quiet agreement on managing future relations. (Lim, pastor of the Light Korean Presbyterian Church and long-time visitor to North Korea, had been in captivity since his unexpected seizure in 2015.)

Canada’s most active engagement with the North has been through its humanitarian assistance and people-to-people relationships. Official aid has for many years been delivered through UN auspices.[4] Also over many years, Canadian religious groups with a long missionary heritage have shown sympathy to the plight of the North Korean people by sponsoring delegations (e.g., United Church of Canada), directly providing relief and food (e.g., the Mennonite Central Committee), and supporting the efforts of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Civil society networks, such as CanKor, looked to inform Canadians about North Korea and to encourage dialogue. While some NGOs have ceased activities or had them terminated (e.g., the Canadian Foodgrains Bank), others remain active, such as First Step, which is devoted to child nutrition. These groups seek to avoid political controversy. The HanVoice organization alternately advocates for human rights, lobbies in Canada, and devises proactive strategies to disseminate information across the demilitarized zone. Korean church communities in Canada have sponsored active programs delivering humanitarian assistance and supplies in the North, but must carefully avoid being seen to proselytize.

What is There for Canada to Do?

Regional actors no longer regard Ottawa as an engaged player on matters of North Korea. They see us with little skin in the game and thin networks from which to mobilize. This has not deterred concerned Canadian observers, especially former diplomats, from prodding Ottawa to assume a more proactive, facilitative role, nor even Canadian diplomats, such as Ambassador to China John McCallum, from offering to do so. This reflects an instinctive sense of Canada’s role as an intermediary, a neutral third party able to gain the confidence of opposing parties and identify their common interests.

A number of possibilities present themselves to the government and to concerned Canadians and NGOs for the immediate, short, and long term.

Short term: First, of course, is remaining open to being a conduit between the concerned parties, being alert to niches through which communication and information can be funnelled, particularly to Pyongyang. Ensuring that channels are available to both sides is critical. Canada has in the past served as a neutral meeting place for disputants (e.g., the United States and Cuba), and while this opportunity is infeasible on Canadian soil, our diplomatic personnel and facilities abroad are resources that could prove of service. Our senior officials, including Minister of Foreign Affairs Chrystia Freeland, do take the opportunity of conversation with counterparts on the sidelines of multilateral meetings.

Second, Canada needs to remain attentive to the human security crises that pervade North Korea. Sustaining our humanitarian assistance programs is important, not only for relief to North Koreans in need, but also to make apparent to Pyongyang that Canada continues this support, even in the face of political/security tensions.

Third, increasing exposure for both sides in informal, unofficial contexts is a priority. This includes support and expansion of NGO activities and people-to-people initiatives. It also should encompass Canadian Track 2 initiatives for regularized and ad hoc meetings of experts, academics, and officials (retired or in their acting, but private, capacities).[5]

Mid-term: Beyond regional security dialogues, an array of functional issues, including energy infrastructure, agricultural practices, and environmental sustainability, are highly relevant to North Korea – all topics on which Canada has extensive expertise. Limited sharing of this expertise quietly goes on now, such as through the Canada-Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Knowledge Partnership Program at the University of British Columbia, which brings a small cohort of North Korean academics to campus for courses in market economics. There is scope for it and other analogous programs to expand, especially as Pyongyang is comfortable situating such programs in Canada.

On the broader international stage, Canada should look to engagement with regional and international partners, especially in partnership with other activist “middle powers” like Australia and the Scandinavian states. This would involve acting to ensure that when actions are taken to sanction or pressure North Korea, an alternative door is left open – in other words, being proactive to advance dialogue, even as we join in condemning nuclear and missile tests.

A pedestrian looks at a TV screen displaying a map of Japan (R) and the Korean Peninsula in Tokyo on September 15, 2017, following a North Korean missile test that passed over Japan. Photo: Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP/Getty Images

The prospect of missiles flying across the Pacific has opened, yet again, the debate over joining the United States’ ballistic missile defence system, as much for the prospect of intercepting missiles directed or misdirected toward Canada as for bolstering our North American alliance status. This option, previously rejected by Prime Minister Harper, does not appear to be gaining traction with the Trudeau government, despite suggestions that the United States disavows formal responsibility to extend protection to Canada.

The long game: The scenarios for the future certainly are contingent on whether or not conflict breaks out. With conflict will come security, economic, and political crises of monumental proportion – in essence necessitating a remaking of the regional order. Canada, unlikely to participate in any conflict, could be called upon to contribute to a post-conflict, multilateral institutional architecture. Ottawa also needs to evaluate how it can and will respond to the immediate, humanitarian crisis that any attack on civilian populations and cities would cause.

A non-conflict path would avoid the immediacy of chaos and humanitarian disaster, but would still involve creating a security architecture to manage whatever arrangements were made (e.g., a “deter and negotiate” result). Kevin Rudd (former Australian prime minister) and William Perry (former US Secretary of Defence) have taken a lead in setting out its essential parameters. These will have to include: a peace treaty to formally end the Korean War; a stable plan for the Korean Peninsula covering positioning of forces; controlled denuclearization; and, critically, security guarantees for North and South Korea and Japan, supported by the United States and China (possibly also others). This is a daunting agenda – necessarily a multilateral one, in which timing of first steps and sequencing will be critical, and in which “middle powers” could serve important roles.

Planning toward integration of North Korea into the regional and international economic and political system needs to start now. This will involve negotiating North Korean access to development and infrastructure funding; (re-)engaging Pyongyang in weapons control regimes such as the Missile Technology Control Regime and Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty; and drawing North Korea into trade and investment arrangements.[6] While such doors to the North can’t be opened prior to its resolving its nuclear agenda, beginning to lay the groundwork for such steps by, for instance, extending observer status and by expanding “educational” programs for officials and experts is an agenda that Canada and other middle powers could activate.

The Need to Seize the Moment

At time of writing (November 6), there has been no testing or provocations for over a month. We are, in essence, in a calm in the eye of the storm. This is the moment for constructive action around some variant of a “deter and negotiate” strategy. With Xi Jinping having cemented his leadership, and Donald Trump meeting with him and allies (during his ongoing trip to Asia), a co-ordinated strategy along these lines should be advanced to Pyongyang.

Notes

Thanks to Ms. Hyun Ju Lee of the UBC Master of Public Policy and Global Affairs program for excellent research assistance. Errors remain the responsibility of the author. All internet links were active as of November 10, 2017.

[1] For ongoing, expert analysis, see the websites of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientistsand 38 North.

[2] Russia lurks in the background, Putin looking to capitalize on any opportunity to enhance Moscow’s influence in East Asia (at the expense of both Washington and Beijing).

[3] Canada is a member of the UN Command Military Armistice Commission Advisory Group, now largely dormant. However, our Defence Attaché in Seoul represents Canada for six months, every two years.

[4] In 2015-16, Ottawa provided over C$2 million in aid assistance to North Korea channelled through the World Food Programme and UNICEF.

[5] Reinvigorating Canadian participation in, let alone sponsorship of, unofficial, Track 2 processes, is challenging, most directly because of lack of funding and support for academics and experts to represent Canada. For example, we are no longer members in good standing of the Council of Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific, the primary region-wide security dialogue institution. At the official level, Track 1, we will meet North Korean participants through meetings of the ASEAN Regional Forum, on the sidelines of multilateral meetings, and occasional, ad hoc Track 2 meetings. However, these platforms to date have provided no openings for continued dialogue.

[6] Andrea Berger provides further details of possible initiatives along these lines. See “Multilateralizing Approaches to North Korea: The Canadian Case,” at 38North.