The Takeaway

A recent pattern of state-sanctioned forest eviction drives in the northeast Indian state of Assam with the purported aim of increasing the state’s forest cover have raised questions about growing Assamese nationalism and anti-Muslim sentiment in the state, particularly in the aftermath of the exclusionary Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) of 2019. While the state government’s plans align with its goals of preserving indigenous flora and fauna, ‘targeted’ eviction drives suggest that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led state government may have ulterior motives.

In Brief

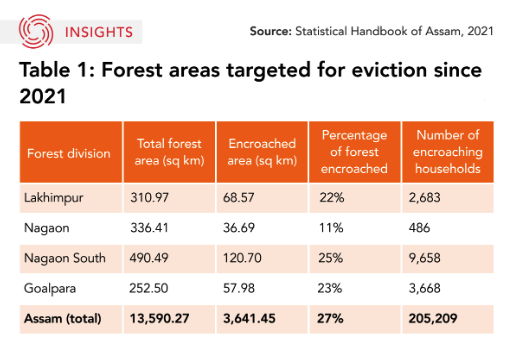

On January 11, the Assam government began an eviction drive to clear 4.5 square kilometres of land in the Pava Reserve Forest in Lakhimpur district, displacing 300 families, mostly Bengali Muslims, who were allegedly encroaching upon the forest land. Since BJP’s Himanta Biswa Sarma took over the state’s leadership in 2021, the Assam government has carried out eviction drives in the Darrang, Hojai, Barpeta, Nagaon, and Lakhimpur districts, most of which have a significant Muslim population. The government plans to continue in Goalpara next. Two recent eviction drives, one in September 2021 and another in December 2022, allegedly “targeted” Muslim communities, resulting in fatal violence and displacing thousands. The violent repercussions of these actions have made the eviction victims wary of protesting.

Implications

The evictions align with the state government’s plans of protecting and upgrading Assam’s reserve forests. In October 2022, Chief Minister Sarma announced plans to increase Assam's forest cover from 36 per cent to 38 per cent over the next five years, primarily by converting reserve forests to national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, which are expected to curb the impacts of flooding and erosion. During the December 2022 Darrang evictions, the Assamese government stated that the land was required for a project to employ Indigenous Assamese youth in agricultural activities. But, as villagers observed, the official boundaries of the Pava Reserve Forest have been changed several times since 2017. Ahead of the 2023 eviction drive, many victims stated that officials made an arbitrary marking around the forest boundary, and in effect, 500 Hindu families also residing on the land were unaffected by the redrawn lines.

Decades-long livelihoods have been uprooted by these eviction drives, as thousands of undocumented immigrant farmers who rely on local forests for their livelihoods have been displaced. Many evictees state that they bought land from locals and have paid land taxes for decades, but the government has often ignored these protestations. Since December 2019, many in Assam have protested the inclusion of immigrants in general, irrespective of their religion, a factor underscored by the ongoing anti-CAA protests in the state. However, the anti-CAA protests have also become a tool to target Bengali Muslims, who constitute a majority of Muslims in the state, fanning anti-Muslim sentiment and Assamese nationalism in the state. As per a recent report submitted to the Assamese government, the state is home to 11.8 million Muslims, of which 4.2 million are Assamese-speaking, with the rest either Bengali-speaking or Urdu-speaking.

Decades-long livelihoods have been uprooted by these eviction drives, as thousands of undocumented immigrant farmers who rely on local forests for their livelihoods have been displaced. Many evictees state that they bought land from locals and have paid land taxes for decades, but the government has often ignored these protestations. Since December 2019, many in Assam have protested the inclusion of immigrants in general, irrespective of their religion, a factor underscored by the ongoing anti-CAA protests in the state. However, the anti-CAA protests have also become a tool to target Bengali Muslims, who constitute a majority of Muslims in the state, fanning anti-Muslim sentiment and Assamese nationalism in the state. As per a recent report submitted to the Assamese government, the state is home to 11.8 million Muslims, of which 4.2 million are Assamese-speaking, with the rest either Bengali-speaking or Urdu-speaking.

What’s Next

- Polarizing politics for electoral gains

Critics say the BJP-led Assam state government’s recent decision to alter the administrative map of Assam by merging multiple districts aims to limit the voice of Muslims in Assam’s politics and is designed to boost the BJP’s seat numbers in India’s 2024 general elections. The BJP won nine of Assam’s 14 Lok Sabha seats in 2019 and aims to increase that number to 12 in 2024. Three of the four merged districts were part of parliamentary constituencies — Nagaon, Barpeta, and Kokrajhar — that did not vote for the BJP in 2019 and have also been recently subjected to eviction drives.

- Climate concerns for Assam’s forests

Assam’s 2004 Forest Policy focused on preserving the natural flora and fauna of forests and wetlands, with an emphasis on meeting the needs of the rural Indigenous and tribal populations. While this policy addresses the rights of socially marginalized communities such as scheduled tribes and castes, there is no mention of other forest dwellers, such as immigrants, particularly those without citizenship documents. Considering that Assam hasn’t had a land survey since 1964, many Bengali Muslim farmers, or char dwellers, continue to remain unaccounted for when planning eviction drives and forest rehabilitation projects. Assam recorded around 58 per cent of the total increase in encroachment of forest land during the 2002-22 period, while also being the only state in northeast India to record an increase in forest cover. An updated land survey, combined with an integrated forest policy that recognizes claims to land by immigrants and adapts to recent climate crises, is essential to move forward without inter-ethnic conflicts.

• Produced by CAST’s South Asia Team: Dr. Sreyoshi Dey (Program Manager); Prerana Das (Analyst); and Narayanan (Hari) Gopalan Lakshmi (Analyst).