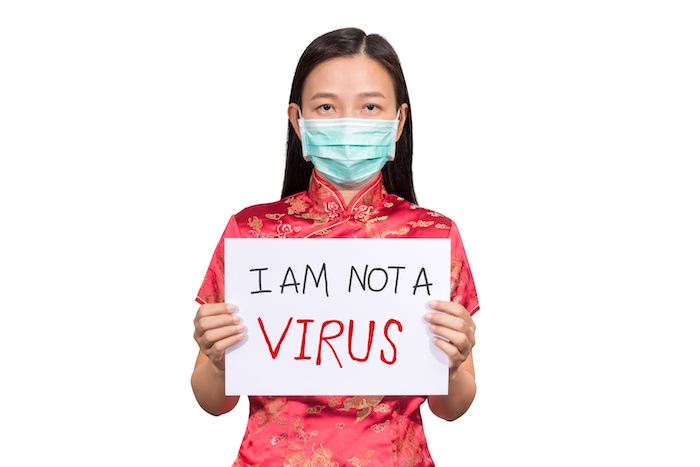

As if the daily stresses to Canadians’ lives from COVID-19 were not enough, the pandemic has metastasized in the country’s public spaces in the shape of virulent racism against Canadian-Asians and Asians in Canada; racism which, in its most malignant form, has resulted in violence. While appealing to the better aspects of most Canadians’ nature, prompting selfless acts of kindness and sacrifice across the country, the pandemic has empowered others to give voice to their previously silent prejudices.

Their victims? The elderly man. The lone woman. The pedestrian. Their means? A bully’s push. A blindside. A slur shouted from the window of a moving car. Their ‘agenda’? Here one can argue, although the underlying thesis is clear enough: COVID came from China; all ‘Asians,’ ipso facto, are bad.

We, as a nation, should not be surprised. History teaches us clearly that there will always be those who work to turn a crisis to their advantage, believing the majority’s distraction provides them a ‘safe’ moment in time to propagate their hate.

What we must collectively realize, however, is that these few, these meagre, individuals do not represent us as a society. They are, rather, pandemic opportunists seeking to sow discontent for the sake of their own distorted pleasure.

What we must collectively realize, however, is that these few, these meagre, individuals do not represent us as a society. They are, rather, pandemic opportunists seeking to sow discontent for the sake of their own distorted pleasure.

Yet it is not, unfortunately, so simple as this. One thing we’ve learned from media studies on crisis-time communications is that fringe ideas, conspiracy theories, and rumours thrive in times of uncertainty and fear.

Recent domestic polling shows a significant uptick across Canada of what can only be accurately portrayed as ‘anti-Asian’ sentiment, up to and including the perception among some that all ‘Asians’ carry COVID-19. The language of racism has further entered Canada’s political lexicon, with one Conservative MP calling the nation’s top public health official’s patriotism into question because of her Chinese ethnicity.

APF Canada Says NO to Hate . . .

APF Canada is proud to be a signatory to a Business Council of British Columbia statement denouncing the recent rise in racist attacks in B.C., a document signed by more than 200 business, community, cultural, and faith leaders condemning these deplorable incidents and standing up for diversity and inclusion.

While Canada is not yet at the ‘ask China’-level of Asian-directed racism one sees in U.S. politics, is this where we are heading? We, at the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, don’t believe so. And neither do the findings from several relevant polls on Canadian’s views of Asians and/or Asia indicate this current moment in time is representative of Canadian-Asia relations in their entirety.

In 2017 and 2019, APF Canada conducted two nationwide polls on Canadian views of Asia, one targeting young Canadians and the other Canadian views on Asian immigration. Far from identifying structural, anti-Asian racism across the country, both polls showed clear acceptance of and desire for more ‘Asian’ involvement in Canada, particularly among the country’s younger generations.

In the 2017 poll, Canadian Millennial Views on Asia, young millennials registered a 61% favourability rating toward Asia and expressed interest in learning more about Asia through in-region study and/or work. In contrast to older Canadians, Canadian millennials were more open to engagement with Asians from all Asian countries –including China – and were clear they differentiated between Asian peoples and their respective systems of government. This point is important as Canadian millennials expressed a desire to engage with China even while disagreeing with the country’s political ‘values.’

Notably, Canadian millennials registered a similar level of dissatisfaction with the United States government as with the Chinese state, arguing the former was ‘dysfunctional’ while the latter was ‘authoritarian.’

In the 2019 poll, Canadian Views on Human Capital from Asia, 53% of Canadian respondents disagreed that the costs of Asian immigration outweighed the benefits, and more than 62% stated they were open to more immigration from Asian states including the Philippines, South Korea, and Japan. Notably, only 61% of respondents favoured more immigration from the United States. Overall, respondents were particularly supportive of Asian immigrants, as they perceived them to be strong in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) skills. This finding accorded closely with the 2017 poll, where Canadian respondents stereotyped Asians as ‘hardworking.’

Within both surveys, China admittedly stood out as an Asian ‘outlier,’ albeit not to the extent that one might expect given the country’s negative media coverage. In the 2017 poll, Canadian millennials registered more positive views of China and argued for closer engagement with the country, even while clearly stating that China didn’t share Canada’s values. In the 2019 poll, 48% of respondents argued for continual Chinese immigration to Canada. To put this percentage into context, the Asia Pacific Foundation conducted this poll seven months after the Chinese government detained Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig.

What can we learn from these national-level data points on Canadian views of Asia? First, younger generation Canadians are far less likely than older generations to have a negative view of Asia, including China. Indeed, younger Canadians look to the Asian region as a source of prosperity, education, and innovation while at the same time holding more critical views of the United States.

#DifferentTogether . . .

APF Canada stands behind the Hon. Janet Austin, Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia, and the anti-racism pledge and video she has released featuring all parties represented in the B.C. Legislature encouraging everyone across the province to participate.  Join us in celebrating the diversity that gives us an advantage in a rapidly changing world: Take the #DifferentTogether pledge.

Join us in celebrating the diversity that gives us an advantage in a rapidly changing world: Take the #DifferentTogether pledge.

As we look at the current environment and wonder whether Canada is becoming less hospitable to Canadian-Asians or Asians in Canada, it is worth noting that younger demographics favour more robust Canada-Asian ties. As provinces such as B.C. are now including more modules on Asian history, Asian culture, and Asians’ contributions to Canada’s development at the primary and secondary school levels, it is likely such favourable trends will continue.

Second, Canadians, by and large, remain open – indeed eager – for more Asian immigration to Canada, particularly when Asian immigration supports the country’s STEM-related industries. Indeed, with respect to some Asian states, Canadian support for immigration from Asia is greater than support for U.S.-originating immigration. Again, the trend lines point to closer Canada-Asia ties and a deeper understanding among the Canadian population of the importance of such ties.

Third, Canadians remain open to engagement with China, even when they clearly understand the difficulties around Canada-China relations and disagree with the country’s political values. While some contemporary polls suggest this perception may have changed, it is worth remembering that Canada is in a moment of crisis and that ‘blame China’ has become a well-publicized meme for many governments seeking to deflect blame.

Does this excuse the growing anti-Asian racism we see across Canada? Absolutely not. It does, however, provided much needed context to the country’s real sense of self. Canada has not become a hostile place for Asians, despite the foul actions of the few. Canada is not the sum total of its worst parts. Canada is better than this.