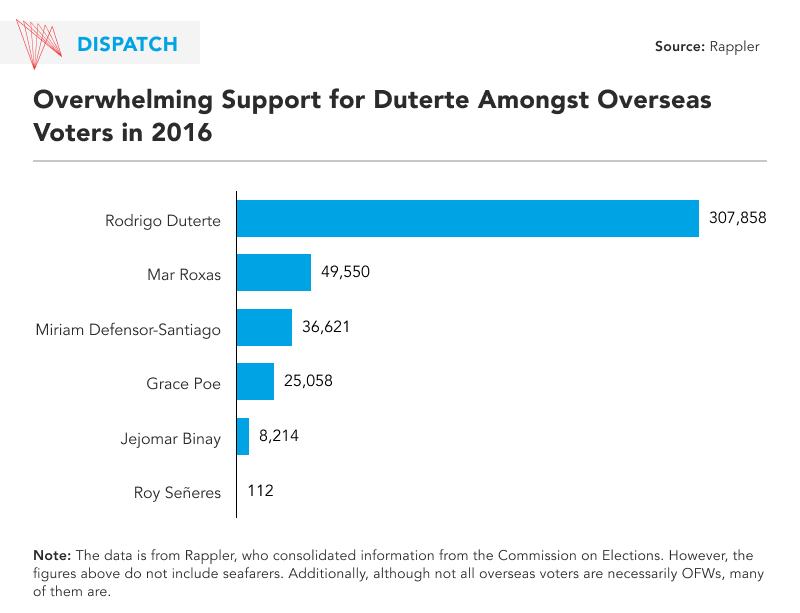

In 2016, overseas Filipinos were among President Rodrigo Duterte’s biggest supporters in his successful bid for the presidency. His vote share among this group was more than six times that of the next-highest candidate and considerably higher than his vote share within the Philippines itself (71% vs. 39%, respectively).

As Duterte’s single six-year term as president comes to a close, he is delivering on some of the promises he made to overseas Filipinos, including roughly 2.2 million Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs). For example, in 2018, his government created the Overseas Filipino Bank to assist OFWs in sending remittances back to their families in the Philippines. And on December 30, 2021, his government established the Department of Migrant Workers. By centralizing services ranging from the recruitment and deployment of OFWs to addressing concerns related to human trafficking and abuse, the new department will purportedly better serve and protect these workers. In Duterte’s own words, “it’s going to be a department to take care of them.”

Among the candidates to succeed Duterte in the May 9 presidential election, the two leading in the polls have put forward quite distinct visions of the role of international migration. Whereas one would continue with Duterte’s focus on international labour migration as part of the country’s post-pandemic economic strategy, the other is encouraging a re-think of this position. How did the export of labour become so integral to the Philippines’ economy? And what is at stake for this policy as Filipinos, both within the country and overseas, head to the polls?

The Labour Export Policy (LEP) and its legacies

International labour migration has a long history in the Philippines, beginning in the late 19th century when the first group of Filipino labourers arrived in the U.S. and eventually settled in various parts of the country to work in agriculture, fisheries, restaurants, and as domestic workers. But it was not until much later in the century that an unprecedented number of Filipinos began leaving to seek better economic opportunities abroad. A little-known fact about this latter wave of out-migration is that it was borne out of crisis. During the roughly 20-year reign of Ferdinand Marcos Sr. (1965-1986), the government took on US$165 million in loans from the World Bank (about US$1.3 billion in today’s dollars) – debts that led to high unemployment and socio-economic unrest. In 1974, to address the crisis, Marcos created the Labour Export Policy (LEP), which systematized the outflow of Filipino workers. Its purpose was to mitigate widespread joblessness and poverty while reaping economic benefits from the dollar remittances of migrant workers.

But the LEP was intended to be only a temporary solution; once the country recovered economically, government intervention to send the country’s workers abroad would be withdrawn. However, two main factors – continuing demand in the world labour market and the stagnancy in the Philippines’ economic development – turned what was meant to be a transition policy into a strategy for economic survival. Since Marcos’s tenure, successive Filipino governments have thrown their support behind labour emigration, many of them focusing on laws and policies broadly aimed at providing safeguards and promoting the welfare of OFWs. Cumulatively, the effect of these policies is the institutionalization of international migration as an important part of economic development in the Philippines.

Where the candidates stand on international labour migration

Several candidates running to be the Philippines’ next president have offered their own plans to support and appeal to OFWs. Many of these plans overlap, focusing on the well-being of overseas workers and their families. However, one crucial difference is how they prioritize international labour migration in relation to local job creation. While all candidates say they want to support local job growth as a means of keeping workers in the country and welcoming returning overseas workers home, they differ in the extent to which they prioritize the local over the international market.

Presidential frontrunner Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. seems to be focusing on marketing Filipinos on the international stage. He supports Duterte’s new Department of Migrant Workers and is calling for its speedy formation in anticipation of increased global demand for migrant labour following the pandemic. He has also shared his own ambitions to support OFWs by building a hospital and establishing health insurance, scholarship grants, retraining programs, and a retirement plan for these workers and their families.

But despite putting forth a plan to retrain OFWs who return to the Philippines, Marcos Jr.’s program is designed to propel these workers back into the international labour market. After all, he describes this retraining program as needing to have “an eye to looking at the labor market, the international labor market,” then adding, “where can we export?” Some warn that continued reliance on labour exportation may absolve the government of its obligation to boost jobs at home. This is not to say that Marcos Jr. does not want overseas workers to have more local job options – he has claimed that the ideal would be for these workers to remain in the country. However, he believes that the Philippines is “a long way from that,” further suggesting that a Marcos Jr. presidency would continue, if not enhance, the labour exportation policies started under the Marcos Sr. presidency.

Vice-President Leni Robredo, currently running a distant second in the polls, recently laid out a multi-pronged approach to support OFWs. If elected, she plans to implement a reintegration pension fund for returning overseas workers. Robredo also wishes to scale-up a successful initiative she implemented in her hometown of Naga City, where she created a one-stop resource centre to help families communicate with OFWs and support them with the hardships they face while their loved ones are abroad. She also expressed that Philippine embassies and consulates must better support Filipino workers abroad, particularly undocumented workers who are especially vulnerable to exploitation.

But what most sharply distinguishes Robredo’s proposed strategy from that of Marcos Jr. is its emphasis on creating more jobs at home. Her plan focuses on eradicating corruption to stimulate local economic development. She argues that only by building an accountable government will foreign direct investment increase and local jobs be created. In addition, Robredo wants to increase the country’s agricultural budget and provide stimulus packages to support small businesses like local farms. These initiatives are intended to help OFWs return to the Philippines by giving these workers and their families a pathway to make a living from farming, a reality that has not been possible before due to a lack of government support. This focus on local job growth reflects Robredo’s hope for more Filipinos to remain in – or return to – the Philippines instead of viewing working abroad as their only option to support themselves and their families.

The wider impact of Filipino labour migration and remittances

For Canada-Philippine relations, international labour migration presents mutual benefits – for the former, a strengthened labour force, and for the latter, better economic opportunity for them and their families. For many living in the Philippines, monies sent home from OFW relatives have raised living standards and provided access to education. For the OFWs themselves, higher wages while working abroad economically empowers them and improves their social mobility. In 2020, cash remittances sent to the Philippines by OFWs based in Canada amounted to US$1.03 billion – a marginal increase from the value in 2019, which was US$1.02 billion. Rising rates of joblessness in the Philippines and economic instability exacerbated by COVID-19 may have led to some Filipino families’ increased dependence on these payments.

But the impact is also felt in migration countries like Canada, which is popular not only for the value of exchange rates in remittances but also because of pathways to permanent residence through temporary foreign worker programs.

For instance, under Canada’s Caregiver Program, migrant caregivers become eligible to apply for permanent status after 24 straight months of work. Canadian hospitals and Long-Term Care (LTC) homes have heavily depended on Filipino nurses and Care Aides to carry them through the COVID-19 pandemic. Facing nursing shortages, the Saskatchewan Health Authority announced in January that it hopes to recruit at least 150 and as many as 300 internationally trained nurses, with a focus on workers from the Philippines. And British Columbia has made substantial changes to its Provincial Nominee Program, including prioritizing applications from childcare workers and health-care professionals.

Continuing or moving beyond international labour migration?

Although politicians like Marcos Jr. have celebrated the recently announced Department of Migrant Workers, some labour rights groups, scholars, and even some Filipinos working abroad, are skeptical. Dolores Balladares-Pelaez, a migrant domestic worker and chairwoman of United Filipinos In Hong Kong, thinks the new department is unnecessary. In her view, better reintegration programming and local jobs will help OFWs more than reorganizing the bureaucratic structure that regulates these workers. Other experts contend that the new department will further institutionalize international labour migration into the fabric of Filipino society. Even NGOs that support Filipino workers in Canada, like Migrante Ottawa, view the Labour Export Policy as simply a “band-aid solution” that does not address joblessness and poverty in the Philippines. Clearly, some are questioning the Philippines’ long-standing strategy of international labour migration. These groups are instead urging the government to move beyond this system by creating more jobs in the Philippines.

Nevertheless, millions of Filipinos continue to rely on international labour migration to improve their own socioeconomic situations and those of their communities. It is no wonder, therefore, that the once temporary labour-export policies have persisted to this day: Remittances increase the Philippines’ economic standing by increasing the economic standing of the families and communities left behind when migrant workers seek opportunities abroad. In addition, as countries around the world, including Canada, continue to face labour shortages, the global demand for migrant labour is expected to increase in the coming years. While the pandemic revealed the instability of international labour migration, causing at least half a million OFWs to return to the Philippines, the shock does not seem to have been great enough to end the world’s reliance on migrant labour. Perhaps moving beyond international labour migration is simply not an option – not for Filipinos or countries that rely on their labour.

While the outcome of the upcoming election in the Philippines is yet to be determined, what is certain is that the policies supported by its winner will have a profound effect on the labour landscape, both in the Philippines and in Canada.