China released its latest Five Year Plan (FYP) on March 12, 2021, following its approval at the ‘Two Sessions,’ China’s annual legislative meetings. Setting objectives for a wide array of economic and social priorities, importantly, the 2021-2025 FYP reaffirms the place of innovation at the core of the country’s modernization and the increasing importance of “indigenous innovation.” While analyses on China’s five-year plans, especially in the English-language literature, tend to focus on policy- and target-setting at the national level, much of the implementation occurs locally and in a decentralized manner across China. In provinces, cities, and villages, there is significant market space and flexibility for experimenting with policy implementation at the sub-national level.

As Beijing aims to have a digital economy generating 10 per cent of national GDP by 2025, local governments are planning various paths to best leverage the opportunities this objective presents. Apart from Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen – already well-established Chinese tech clusters – the country is nurturing a new crop of thriving tech hubs. Several so-called “new first-tier cities” – cities with less economic and political weight than the four megacities but are growing in influence – are catching up by investing in next-generation tech sectors, readying to contribute to the country’s quest for high tech autonomy.

An important mechanism through which cities can achieve this abstract goal of achieving tech autonomy is by obtaining a National Technology Center designation, which confers not only strategic importance but also helps attract significant public and private investment. By officially announcing their bid for this designation, the cities of Xi’an, Chengdu, and Wuhan are stepping up to lead as tech hubs, and tracking their trajectories will provide a more comprehensive understanding of China’s latest FYP and its unfolding over the next five years. Wuhan, in particular, offers an opportunity to explore the rollout of the innovation directives included in the country’s new FYP.

China’s ‘Optics Valley’ – the next innovation powerhouse?

Wuhan (in Hubei Province), which made international headlines as the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic last year, is strategically located by the Yangtze River and serves as a transportation and manufacturing hub. While it is unusual for FYPs to mention cities by name, the latest FYP refers to Wuhan as the next “critical pole of development” and designates it to support the building of middle- and high-end manufacturing bases and industrial clusters in central China. Besides its location and economic prowess, the city has a good foundation in advanced manufacturing, especially in the field of optoelectronics, electronic devices and systems that source, detect, and control light.

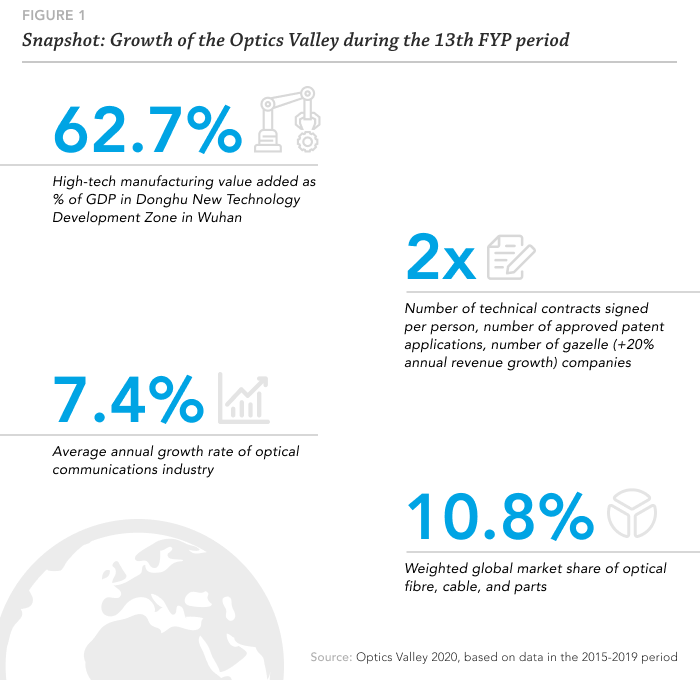

Wuhan began making its mark in the optoelectronics industry in the 1990s. The 1988 establishment of the Donghu New Technology Development Zone – touted as China’s ‘Optics Valley’ – helped lay a solid infrastructural foundation, and the city quickly emerged as the “state-level optoelectronics industry base.” By the end of the previous (thirteenth) Five-year Plan period, Wuhan had become the world’s largest base for optic fibre and cable production, with more than 100 companies in the city’s C$110-billion optronics cluster. Notably, Yangtze Optical Fiber & Cable, the world’s second-largest fibre optic cable company, with a 12.7 per cent global market share, and China’s major telecommunication equipment producer Fiberhome Telecom Tech are both headquartered in Wuhan.

With relevant technologies and experience that could be applied in producing optoelectronic chips, the industrial cluster has expanded more recently to include growing semiconductor manufacturers Yangtze Memory Technologies and Wuhan Xinxin Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp., specializing in 3D NAND and NOR flash chips, respectively. Chinese telecom giant Huawei also chose the Optics Valley area to base its semiconductor manufacturing supply chain, which is expected to form an important part of the company’s largest R&D centre in central China.

The 14th FYP will empower Wuhan to leverage its strengths in the fibre optic industry to cement its spot as the next national innovation centre. According to the current FYP, a “high-speed, integrated, efficient and safe” 5G network with “56 per cent penetration rate” will form the core of China’s future informational infrastructure. Emboldened by these objectives, Wuhan is looking to establish by 2025 a globally competitive ecosystem comprising seven pillar industries, including fibre optics, chips, display screens, terminal and network devices, and cloud and smart technologies. More specifically, the city envisions breakthroughs and upgrades in the areas of optical communication, integrated circuit, display panel, cloud computing, big data, the Internet of Things, and artificial intelligence.

To achieve these goals, the Wuhan city government set forth several key strategies for the next five years, shortly after the central government released the outline of the 14th FYP in October 2020. One noteworthy aspect of these strategies is an emphasis on industry-led innovations – a departure from China's largely top-down approach to tech development. As envisioned in Wuhan’s key policy document, the new innovation system will see the emergence of tech champions possessing “self-developed, controllable technologies” with market forces playing a leading role. Instead of the common model in China of relying on academic research labs for R&D efforts, a ‘1+N’ model will be established, allowing a leading company to initiate projects with multiple partners. The city also announced the provision of C$255 million (1,350 million yuan) in R&D funding to bid-winners through five major projects. As such, the government is positioning itself more as an infrastructure-builder and investor rather than a controlling agent. This is consistent with Beijing’s attitude toward advancing financial technologies over the past decade, providing a relatively less regulated space for private sector-led experimentation to take place.

Another strategy Wuhan is developing is to leverage its strength as one of China’s major educational hubs and create a more conducive system for high-end tech talent to work and start businesses in the city. For its part, Beijing is generally supportive of talent moving away from the over-crowded “Bei Shang Guang” (the colloquial umbrella term for Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou), with measures such as creating new development hubs and skilled job opportunities in tier-two and tier-three cities to help improve regional equality and thereby reducing much-felt population pressure in its busiest metropolises.

Local governments of the new first-tiers have been stepping up campaigns in recent years to lure fresh graduates. In the case of Wuhan, since the launch of the ‘One Million College Graduates Entrepreneurship and Employment Program’ in 2017, the net inflow of talent has been continuously rising. In 2020, the proportion of bachelor’s degree graduates from Wuhan University and Huazhong University of Science and Technology staying in Hubei province were 26 per cent and 39 per cent, respectively, and the total number of bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. graduates that chose to stay in Wuhan reached 302,000, despite the onset of the pandemic. Policies around job creation, minimum wage, subsidies, and, perhaps most importantly, the city’s strong economic performance in the past years have all contributed significantly to this trend. On the other hand, a stark contrast remains in the number of overseas-trained talent residing in Wuhan. Currently, the city only has about 300 foreigners and overseas-educated Chinese who are regarded as leading experts in fields of strategic importance to China, a number too small to give its pillar industries a “talent boost” and a challenge that Wuhan still needs to address.

Barriers to success

There are several barriers to Wuhan’s ambitions, reflective of broader challenges on China’s road to technological self-reliance. China has been the world’s largest semiconductor market for more than a decade, and it consumed in 2020 C$180 billion worth of semiconductor wafers, or integrated circuits, 16 per cent of which were manufactured in China and six per cent produced by China-headquartered companies. Given this significant gap in demand and supply, China’s heavy reliance on imported chips and critical chipmaking technologies renders production – in not only the semiconductor industry but also of end-users like drone and smartphone manufacturers – extremely vulnerable to the increasingly tightened export restrictions imposed by the U.S. and its partners.

This gap is challenging to address given the highly monopolized and complicated nature of the global chipmaking supply chain. Capabilities in each area, be it chip design or gear production, are essential to longer-term success and take time to develop. The U.S. maintains a dominant position in the global semiconductor supply chain, and its value-added share can be as high as 74 per cent in the critical components of Electronic Design Automation (EDA) and core IP, dwarfing China’s three per cent share. Even China’s largest chipmaker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), is three to five years behind global leaders in its technological progress, not to mention the recent hit it faced when Washington decided to cut off supplies of essential chipmaking equipment to SMIC, which could take as long as 10 years for China to produce locally.

The deeper systemic issue in China’s and Wuhan’s chip manufacturing drive is the belief that leapfrogging is possible with heavy investment and imported technologies and talent, while overlooking the current incapability to effectively apply technologies to actual chip production. Wuhan’s Hongxin Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (HSMC) is an example of a Chinese grand chip manufacturing project in recent years that failed to live up to expectations. Once a star company, HSMC had to devote nearly C$1 billion to purchase a core chipmaking machine from ASML, the Dutch firm specializing in the type of tools required for making the most advanced chips. The machinery was subsequently pledged as collateral for bank loans when the project officially grounded to a halt last July. While reliance on imported equipment may have only contributed in part to HSMC’s failure, more significant problems lie in the many technology patents and monopolized operations that cannot be developed indigenously within a short period of time, especially for a semiconductor industry late-comer like China, whose R&D foundation is still largely absent.

Wuhan’s semiconductor challenge is emblematic of the kind of “technological chokepoints” – areas critically constraining the future of industries that will need to be cleared – that China hopes to overcome in the 14th FYP period. Wuhan also has a long way to go in catching up with other cities and provinces racing to build their own semiconductor brand – Hubei province only ranked 20th in integrated circuit (IC) production in 2020, although it made commendable progress with a 2,300% increase compared to its IC production level in 2019, despite COVID-19 disruptions. It remains to be seen whether Wuhan, in its effort to grow a globally competitive chipmaking industry, will be able to learn from its failures and get the pace and ingredients right in the next five years.

The way forward

China’s newest five-year plan reveals a blueprint for accelerating the uptake of technological innovation in reaction to new domestic and international realities. By not setting any specific GDP targets in its latest FYP for the first time, Beijing has made the pivot towards a “quality over quantity” mindset in the next phase of China’s development. Meanwhile, Wuhan is at the juncture of several policy priorities, including the development of new inland city clusters, the acceleration of digitalization and its underlying infrastructure, and the enhancement in R&D and manufacturing capabilities – all of which could support the operation of a more complete, independent supply chain for strategically-important sectors countrywide.

As the pandemic-triggered global shortage of semiconductors demonstrated, China has an acute problem vis-à-vis an already significant demand-and-supply gap in the chip space. The course that Wuhan has plotted for the 14th FYP period to help fill this gap will be an important development to watch in the years to come. High-tech is becoming the new lens through which countries’ power relations are viewed, and international R&D collaboration is becoming an increasingly central issue to a broader group of stakeholders beyond academia. It will be all the more important for countries, including Canada, that are likely to continue engaging with China to have a continuously updated understanding of the opportunities, challenges, and, perhaps more importantly, the sensitivities around these issues in order to make informed decisions when it comes to each business, investment, and academic exchange.