What a difference a year makes. Just 12 months ago, Canada and China were looking forward to celebrating the final month of the ‘2018 Year of Canada-China Tourism,’ a form of economic diplomacy that four in five Canadians broadly agree with, according to opinion polling conducted by the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. On another economic front, foreign direct investment (FDI) dollars, a perennial concern in Canada, were continuing to tick up in both directions between Canada and China, although not at the same levels as at the height of the commodity booms four years earlier.

Diplomatic flashpoint

Then, one particular visitor to Canada from China not only managed to upend a benign tourism relationship, but also trigger a vast array of simmering tensions between both economies. And the investment worries returned.

Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou was arrested at Vancouver International Airport on December 1, 2018 on a U.S. extradition warrant, with a series of moves by China – ranging from freezing meat imports from Canada to detaining two Canadian citizens – widely perceived as retaliatory. While Meng may feature at the centre of these frayed Canada-China ties, other events have since gnawed at this cross-Pacific relationship, from the diplomatic clashes for economic and technological dominance between China and the United States to the deadly, escalating battles in the streets of Hong Kong.

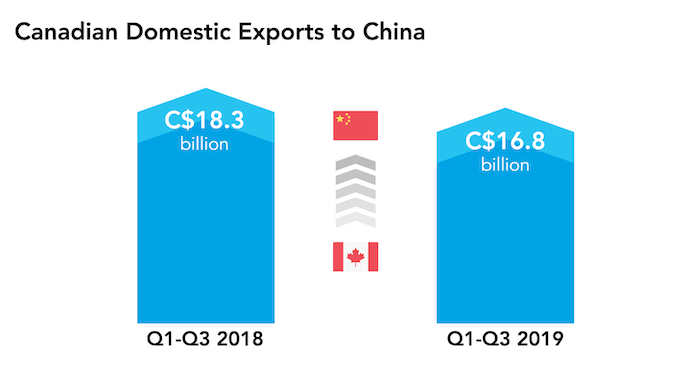

In economic terms, the deepest blow has been to trade. Comparing the first nine months of 2018 to the same period in 2019, Canadian domestic exports to China dropped by C$1.5 billion, or nine per cent. Before this current schism, Canadian domestic exports were on the rise: from 2014 to 2018, Canada’s domestic exports to China grew by C$8 billion, with an average annual growth rate of 10 per cent.

The Chinese investment picture

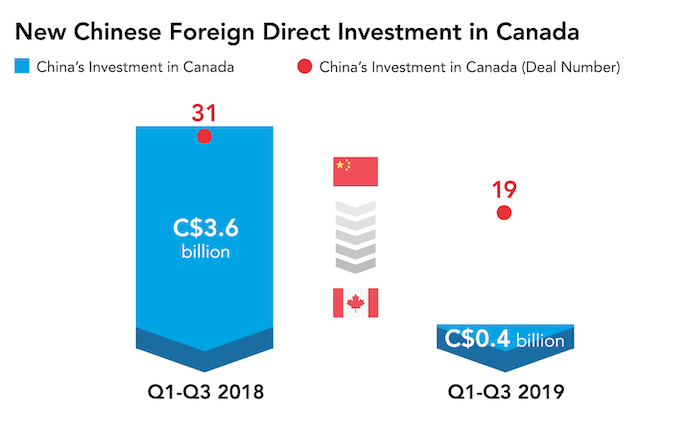

But when it comes to investment, numbers reported in headlines appear to paint an even grimmer picture. According to the APF Canada Investment Monitor, mainland China’s investment into Canada has dropped: from C$3.6 billion [1] in new investments in the first three quarters of 2018, to C$351 million in the first three quarters of 2019.

However, we must be mindful that lengthy investment decision timelines mean the full shape of investment impacts may not be immediately apparent. Additionally, much of that C$3.25 billion difference between 2018 and 2019 was due to two mega-deals in 2018: Chinese CITIC Ltd. agreed to acquire a stake in Ivanhoe Mines Ltd. for C$723 million in June, while Canadian mining firm Nevsun agreed to a takeover for C$1.86 billion by China’s Zijin Mining Group in September of that same year.

Meanwhile, China’s state-owned CITIC has agreed to invest an additional C$612 million in Ivanhoe, while the privately-held Zijin also holds a stake in Ivanhoe and plans to increase it, so expect the dollar value gap to lessen in the near term. Interestingly, these announcements also reflect that the Chinese government does not appear to be directing either the state- or private-sectors to halt major deals with Canada.

Ultimately, the current ‘dollar story’ appears to be directed by both economies’ respective natural resource policies and the timing of business decisions in an industry (mining) that is both capital intensive (meaning any one deal can swamp dozens of deals in other industries) and involves lengthy timelines (externally, from regulators; internally, as companies conduct research and due diligence across years).

A case in point is China National Petroleum Corp.’s C$6-billion investment in the LNG Canada joint venture to build a facility in Kitimat, British Columbia. Funds were released in November 2018, substantially raising China’s total amount invested before bilateral ties became strained. And ironically, a delay of just a few weeks would have seen the funds released in December or January, and the discussion would have been a rather different one – i.e. about China’s investments in Canada vastly increasing after Meng’s arrest.

Beyond the dollar story

Beyond the ‘dollar story,’ and with the above caveats in mind, the number of deals involving Chinese investors has also dropped, from 31 to 19 across the first three quarters of 2018 over the same period in 2019. Tracking the number of deals is another way to measure the ties and degree of interest between two economies, and can contain information that gets ‘washed out’ when otherwise comparing high- and low-capital intensive industries.

The biggest downward shift by this measure was in the finance industry, decreasing from seven to none. Finance last year encompassed both real estate (co-working spaces, realty offices, and companies structured as real estate investment vehicles) and financial services (two investment holding companies). To date, none of the measures or rhetoric seen during the current spat appear to have these sorts of relatively small deals in their crosshairs, making the absence of any finance deals this year all the more notable. China- and Canada-side regulations to limit capital outflows in the former, and curtail real estate investments in the latter, may at least partly explain the shift.

The 31-to-19 deal gap is also partly driven by a collapse in the energy industry (from four deals to none) and the mining and chemicals industries (from five to one). Last year’s energy deals were diverse – including into oil sands, wind farms, waste-to-biofuels, and fuel cells, all of which face different market trends, – so there is no one-size-fits-all economic explanation for the drop. In a similar vein, the mining assets acquired last year varied from mega-deals into Nevsun and Ivanhoe driven by their projects outside of Canada, to lithium mining plays in Quebec and two deals expanding access into mining support services in La belle province. In 2019’s first three quarters, the only deal recorded was one into rare earths in Manitoba. As with energy, no one market trend within mining is sufficient to explain the drop in the number of deals. Still, the Manitoba deal reflects a trend that goes far beyond the one-year spat: China’s longstanding interest in diversifying its resource bases for strategic reasons, especially given the much larger U.S.-China dispute. In essence, any ill-will with Canada can be overridden by far more prominent and long-term strategic concerns.

As with finance, there are no direct indications that mining and energy investments were being specifically targeted over the past year. It appears more likely that multiple, international market forces and domestic regulations have shifted China’s interests from these Canadian industries. Still, given the unusual activity in these sectors this year that cannot necessarily be explained away by the data, it could well be that some level of political activity is informing investment decisions in these vital sectors. Raising the possibility of some China-side influence is the fact that nothing in any public announcements on Canadian Investment Canada Act reviews of incoming FDI over the past year seems to indicate a pattern of increased restrictiveness on the Canadian side.

The Canadian investment picture

Conversely, Canadian investment into mainland China has declined only slightly, as seen in APF Canada Investment Monitor statistics: from C$1.4 billion in new investments in the first half of 2018, to C$1.2 billion in the first half of 2019. [2] As with inbound investment, total dollar values are heavily driven by a few, large investments with timelines set in advance of the current economic dispute. The bulk of 2019’s investment came via Canada-based Electra Meccanica Vehicles’ February opening of a C$784-million facility in Chongqing; and, the bulk of the first half of 2018 from Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB)’s C$800-million commitment to real-estate projects in Chengdu and Shanghai. While CPPIB outbound activity towards China has been comparatively subdued compared with years prior, its April 2019 Annual Report did not flag any reduced interest in investing in China. And while risks were acknowledged due to the China-U.S. spat, China appears to still be part of CPPIB’s strategy to increase emerging market investments as a share of its overall portfolio.

Larger forces at play

Regardless of whether Canada wants to see its investment relations with China get back on track, or whether the past year’s disputes give investment decision-makers pause, it is clear that responses need to be tailored beyond just top-level, aggregate dollar totals. Drilling down within the past year, and into specific sectors and deals, it becomes apparent that most, and perhaps all, of the drop in investment is more a matter of deal-specific timing than anything else. Some trends emerge when deal numbers, not dollars, are counted – but again, this on its own is not enough to suspect direct interference, and much of the shifts appear to be explainable within sector-specific contexts.

Only by analyzing these numbers is it possible to see that some interesting shifts may be playing out in energy and mining one year after Meng’s arrest, a trend obscured if just looking at dollar values announced in headlines. In assessing where Canada finds itself one year in, ‘how much’ is only part of the discussion.

Endnotes

[1] All figures in 2018 Canadian dollar terms. 2019 investment figures were adjusted downward to be deflated to 2018 terms for measurement purposes.

[2] Inbound data for Q3 2019 is still incomplete and yet to be analyzed.