The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada has been monitoring Canadian perceptions of human rights issues in Asia and their expectations of government in addressing these concerns through its National Opinion Polls (NOP) since 2004 and results from our 2020 NOP show that Canadians continue to support the government speaking out against human rights issues abroad. Our 2020 poll further captures deteriorating Canadian perceptions toward China's human rights situation and a negative shift in sentiment toward China generally. As human rights issues flared up across Asia amid the pandemic, and while Canada weighs its relationship with political and economic powerhouses China and India amidst growing human rights concerns in those countries, a deeper understanding of Canadian opinions on human rights in the region is increasingly important.

Canadians continue to support the government in engaging Asia on human rights

Canadians surveyed in our latest NOP express a growing desire for the Canadian government to promote democracy and human rights abroad and speak out against human rights abuses in Asia. For example, 85 per cent believe it is critical for Canada to engage Asian countries on democracy and human rights issues, with a large majority of respondents from all provinces, political leanings, ages, and educational backgrounds sharing this opinion. Canadians have expressed similar opinions in previous APF Canada National Opinion Polls, but not as strongly. In 2018, 49 per cent said that Canada should be a “leader” in advancing democracy and human rights in its relationship with Asia; 36 per cent said “partner.” In 2016, 76 per cent said that Canada should raise human rights issues with Asia rather than leave it to Asian countries to address human rights issues themselves.

The 2020 NOP also reveals Canadians’ hesitancy to do business with Asian countries when there are human rights concerns, to a similar degree captured in previous years. In 2020, slightly more respondents (47%) disagree than agree (45%) that "we can't afford to stop doing business with or in Asian countries just because of human rights concerns.” Middle-aged respondents (35-54) disagree the most, with a majority (54%) thinking human rights concerns outweigh business interests. In addition, 83 per cent of respondents agree that Canada should stand up to China, Canada’s largest trade partner in Asia, when our key national values are on the line, including the respect for human rights and democracy. This opinion is broadly shared by Canadians, with disagreement never exceeding 14 per cent in any sub-group.

A new survey by the Pew Research Center shows similar opinions toward human rights in China for the United States, with 70 per cent of American respondents’ supporting the promotion of human rights in China even if it harms economic relations. This opinion transcends political partisanship, as is the case in Canada.

Canadians perceive a worsening human rights situation in China, but not in India

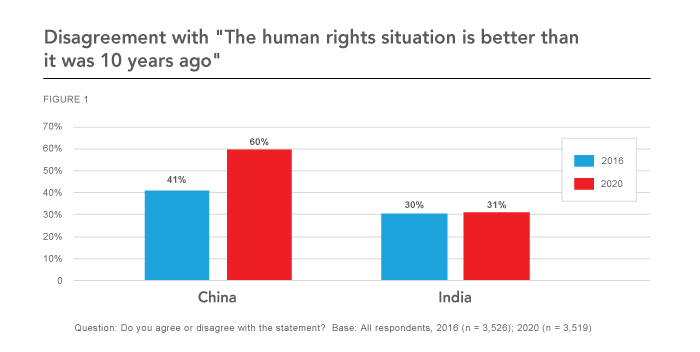

In our 2020 NOP, we polled Canadians on their perception of the human rights situation in both China and India compared to ten years ago. We found a considerable rise in the perception that the human rights situation in China has worsened over the last decade, with a 19 per cent point increase compared to 2016, but perceptions toward the human rights situation in India have remained relatively stable (Figure 1).

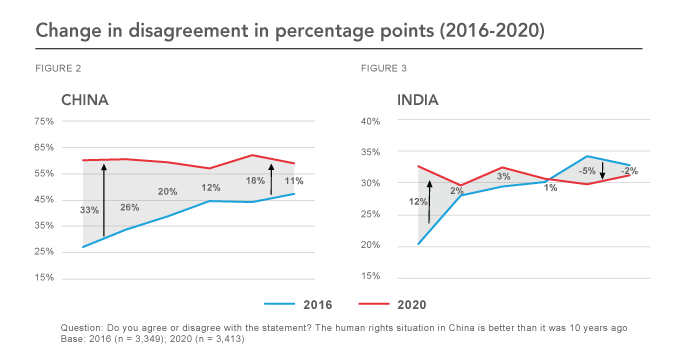

Taking a closer look at Canadians who perceived the human rights situation as worse today than ten years ago in both China and India, we found that the increase is mainly due to the perceptions of younger respondents (18-44), especially the 18-24 age group, for both countries, as well as the 25-34 and 35-44 age groups for China (Figure 2 & 3). Notably, the rise in the perception that the human rights situation in China has worsened among the 18-24 group occurred as the number of respondents in this age group with no opinion on the matter dropped significantly, suggesting a heightened awareness or certainty about the issue in 2020. Beyond this common trend, there are particularities in the responses to this question for China and India when looking at responses by Canadian province.

Spotlight China

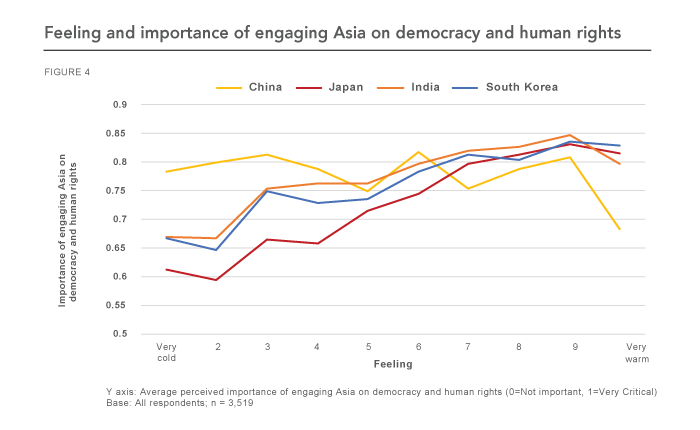

The worsening view of the human rights situation in China is even more compelling when we consider the negative correlation between the perceived importance of engaging Asia on democracy and human rights and Canadians’ feelings toward China (Figure 4). In other words, the more Canadians believe Canada must engage Asia on human rights issues, the more negative their feelings toward China are. Interestingly, we found the opposite relationship for Japan, India, and South Korea, where a stronger belief that Canada must engage Asia on human rights is associated with more positive feelings toward these economies.

It is likely that the perception of human rights in a country plays a role in this relationship and that the worsening perception of human rights in China contributes to the overall declining feeling toward China.

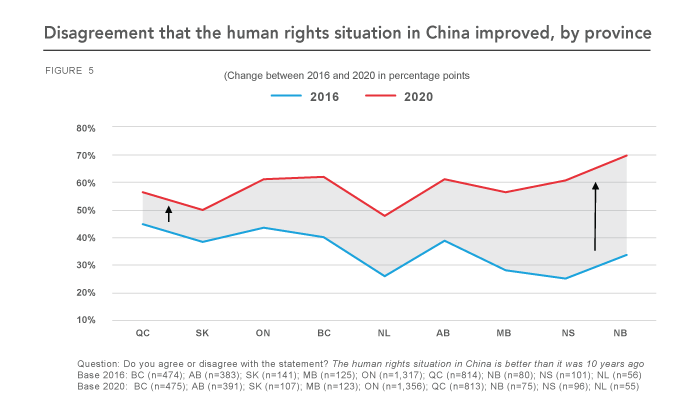

Another interesting finding in our 2020 NOP is the diversity of perceptions towards China across Canada. For example, the provincial breakdown reveals that the perception of the human rights situation in China went from being among the most positive in 2016 for Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to being the most negative in those provinces in 2020. Now at 70 per cent, the perception in New Brunswick that the human rights situation in China has not improved jumped 36 percentage points since 2016, the most of any province, followed by Nova Scotia (35 percentage points) and Manitoba (28 percentage points) (Figure 5). There was a significant decrease in the ‘no opinion’ rate for New Brunswick that is not observed for other provinces, which could also have contributed to the change for New Brunswick.

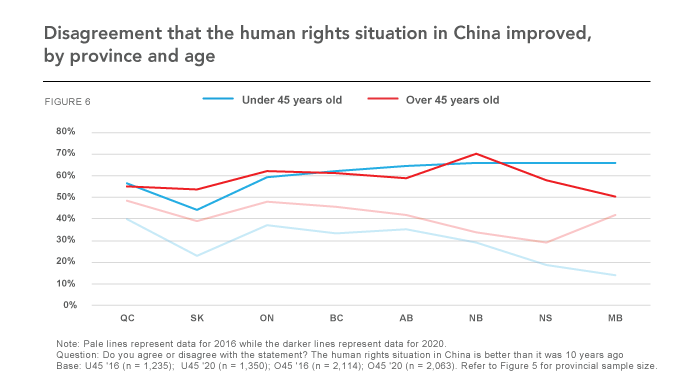

For Nova Scotia and Manitoba, the younger half of the population drove the negative turn in opinion. Among respondents under 45, there was a 52-percentage-point increase in the perception that the human rights situation in China has not improved in Manitoba and a 47-percentage-point increase in Nova Scotia (Figure 6). With that shift, respondents under the age of 45 from Manitoba and Nova Scotia went from having the warmest feeling toward the situation to the most negative of any province in 2020.

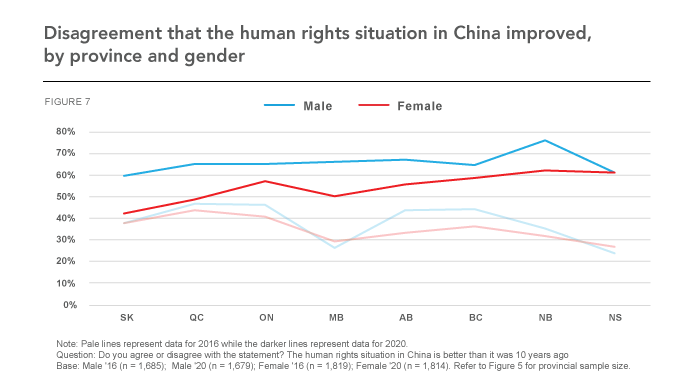

As also shown in Figure 5 (above), Quebec and Saskatchewan both exhibit a modest negative change in the perception of human rights in China but have a more positive perception in 2020 compared to most other provinces. Figure 7 shows that men and women alike from most provinces have a much more negative perception of human rights in China in 2020 compared to 2016. Still, the change is only five percentage points for women in Quebec and Saskatchewan, compared to about 30 per cent for women in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

We found that a steep rise in the ‘no opinion’ rate for women in Quebec and Saskatchewan between 2016 and 2020 is mainly responsible for this minimal change, contrasting with a dropping ‘no opinion’ rate for women in other provinces. A deeper look into the forces at play in these provinces could explain why women appear increasingly unaware or uncertain about the human rights situation in China.

Spotlight India

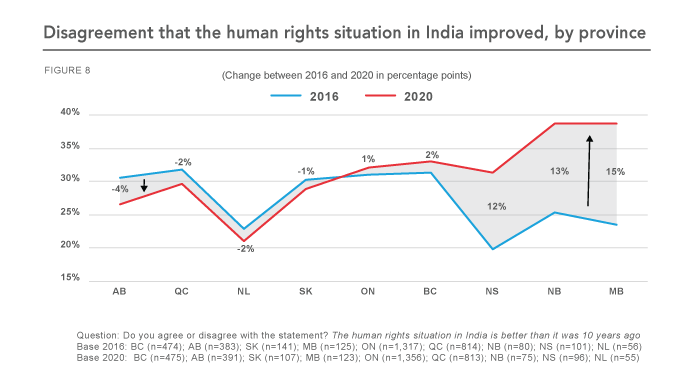

In 2020, we found that 31 per cent of respondents disagree that “the human rights situation in India improved from 10 years ago,” up only one percentage point since 2016. The continuity in the Canadian perception of the human rights situation in India stands in stark contrast with the drop in the perception of China's human rights situation.

Interestingly, the provincial breakdown shows the highest negative turn in the perception of the human rights situation in India for the same three provinces as for China; Manitoba (by 15 percentage points); New Brunswick (by 13 percentage points); and, Nova Scotia (by 12 percentage points) (Figure 8). The change in disagreement for other provinces is marginal, ranging from minus four percentage points in Alberta to two percentage points in British Columbia.

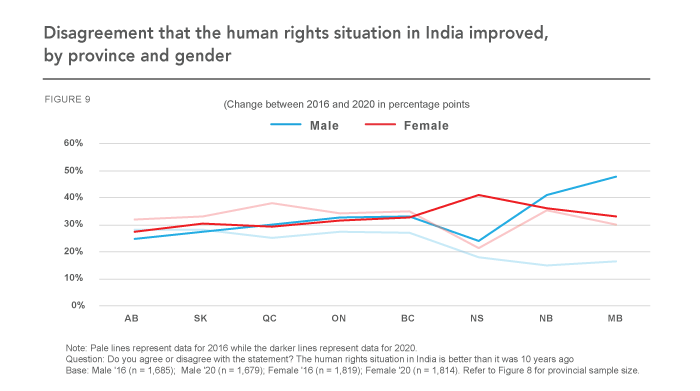

To gain insight into this change in opinion, we looked at different demographics and found a significant gender divide in the change of opinion for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Manitoba, which seems to be responsible for the negative turn in opinion. In contrast, the shift in opinion regarding the human rights situation in China for those three provinces was mostly driven by youth, not differences in opinion between men and women. As shown in Figure 9, for India, the perception of the human rights situation in 2020 compared to 2016 is 31 percentage points more negative for men in Manitoba and 26 percentage points for men in New Brunswick, while it changed by only three percentage points and one percentage point for women, respectively.

Interestingly, we observed the opposite trend in Nova Scotia, where the perception of the human rights situation in India worsened by 20 percentage points for women and only six percentage points for men. In other provinces, the perception of the human rights situation in India for women improved in 2020 over 2016.

Navigating the Canadian public opinion and Canada's ties to Asia

Canadians concerns about human rights in the Asia Pacific matter, as the existence of mutually beneficial economic and strategic partnerships that Canada shares with the region are reliant upon domestic support and on a set of shared values, such as human rights. Our findings point to the worsening perception of human rights in China as a contributor to the overall declining feeling toward China. However, more research on this is required to better understand what exactly drove the negative shift in Canadian’s feelings toward China.

Furthermore, we investigated demographic trends behind Canada’s public opinion regarding the human rights situation in Asia to better understand the negative turn in Canadians’ perceptions on the issue. Overall, we found that the rise in opinion among Canadian youth is the main driver of rising concerns regarding the human rights situation in Asia. While four years ago, Canadian youth had largely no opinion on the human rights situation in Asia, today, Canadian youth are just as concerned about the situation as older demographics. We can only speculate as to what spurred this awakening, but we suspect that recent sustained reporting on human rights issues in Western media, including on social media, played an important role in raising awareness about human rights issues in China. Likewise, there was a sweeping negative shift in the perception of human rights in Asia for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Manitoba. Again, it is hard to identify the cause of the shift in opinion.

As Canada navigates an increasingly polarized environment globally over the questions of values and human rights, data from APF Canada’s National Opinion Polls offer a more in-depth look into the perceptions of Canadians on these issues. This year, we have polled Canadians on balancing democratic values and human rights with economic interests in foreign affairs. Watch this space for the full report on our first National Opinion Poll of 2021 on Canada’s foreign policy, which will be released this summer.

Read our other Dispatches in this series of deeper dives into APF Canada's 2020 National Opinion Poll data:

- Canadian Support for Education About Asia is Strong and Growing

- Media Coverage of Asia and Asian Issues (Coming Soon)