While Western democracies, including Canada, have been spearheading economic sanctions against Russia over its invasion of Ukraine, China has refused to condemn Russia and repeatedly criticized the use of sanctions. China’s official approach to the war in Ukraine and Western-imposed sanctions is known and has been much discussed. But Chinese public opinion on the crisis, and especially on the sanctions, remains less explored. An examination of how the conflict is being discussed on social media in China provides a window into how Chinese public opinion on the war in Ukraine and China’s overall behaviour in foreign affairs is being shaped and shared online.

Social media trends and refined censorship

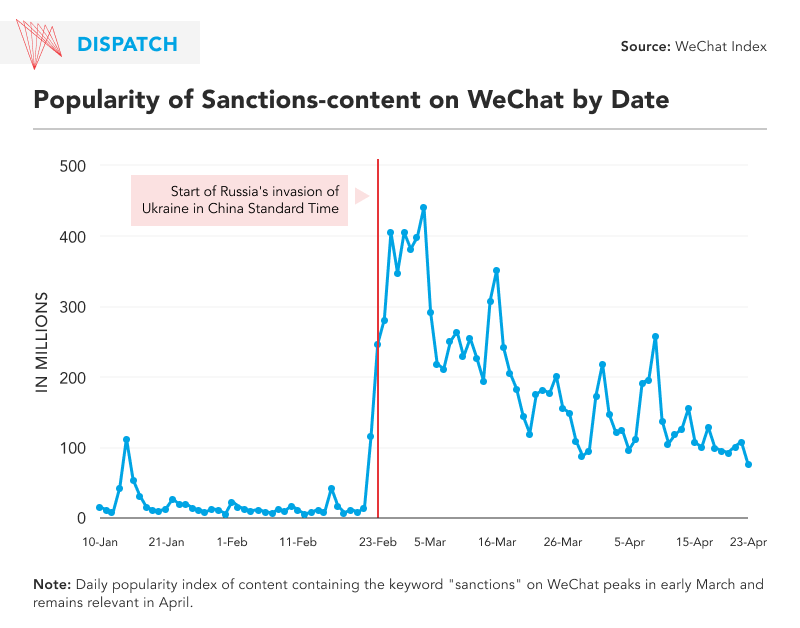

The overall discussion on Western sanctions against Ukraine on the two most widely used Chinese social media platforms, WeChat and Weibo, peaked in late February and early March and gradually declined towards the end of March and early April as a new COVID wave hit China. Relative to their comparable obscurity before the war, sanctions remain a significant topic of discussion on these two platforms at the time of writing, even when other news, such as the resurgence of COVID-19 in China and major metropolitan lockdowns, fills the headlines.

On Weibo, China’s Twitter, trending topics on sanctions peaked on the date of the Russian invasion on February 25, with a total of nine hashtags ranking among the top 13 of the daily 50 hot topics [1]. Sanctions-related content and comments on WeChat, the all-in-one Chinese super app with a billion users, saw an astronomical 421 per cent increase in mid-February, reaching a peak on March 4, with its popularity index shooting well over 500 million points [2]. Comparatively, content about COVID-19 saw its index reach only 100 million points on the same day. The volume and popularity of sanctions-related content mark a significant interest in this relatively new political topic for Chinese netizens.

An analysis of the content found on China’s two leading social media platforms shows that most comments were reactions to the sanctions imposed on Russia or announcements of countermeasures from Russia with a pro-Kremlin or a pro-Beijing perspective. Censorship on Chinese social media played a key role in promoting pro-Russia content that also jives well with Beijing’s stance while under-presenting pro-Ukraine messaging. However, pro-Ukraine content does exist, though it is quickly taken down or buried by pro-Russia content and comments preferred by the censors. Points of view supporting the sanctions cannot gain as much popularity on Weibo or WeChat due to the algorithmic censorship deployed in line with the Chinese government’s priorities.

In contrast to blanket takedowns of unsavoury content and wholesale blockages of criticism Chinese authorities are known for, censors have become more sophisticated in recent years in regulating and strategically directing news coverage when content deemed 'unfavourable’ to Chinese authorities breaks out online. Refined censorship techniques like content manipulation mix mostly official narratives propagated by a diverse pool of opinion influencers with a minor number of alternative viewpoints different from the official narratives. This is demonstrated in the current case, where a combination of well-reported Russia-friendly coverage and a dash of Western counteractions without substantial context have bolstered the popular ‘anti-American’ belief that Western sanctions against Russia are "unjustified.”

Hot topics, hotter takes

Analyzing popular comments on a selection of top sanctions-related content shows that prominent narratives expressed by Chinese netizens focus on the West’s “self-harm,” the U.S.’s “ruthlessness” in wanting to maintain its hegemony, and the lessons that China should take from the sanctions imposed on Russia. On the domestic front, many netizens speculate that China will benefit from the war in Europe as China could take advantage of discounted Russian oil and gas. Based on our review of Chinese social media content since the war began, European Union-imposed sanctions against Russia are specifically seen by Chinese netizens as a backfiring act since the political and economic union relies on Russian energy. Canada’s sanctions are seen, similarly, as a bandwagon-ing gesture that demonstrate its deference to the U.S. and is decried on WeChat and Weibo. Former German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, meanwhile, are seen as smart middle power actors who have maintained positive relations with Russia over the years. A prominent example of smart domestic prioritization, according to Chinese netizens, is Merkel’s approval of continuing Germany and Russia’s Nord Stream 2 energy pipeline despite it being already highly controversial upon agreement. Despite Nord Stream 2’s threat to the EU’s geo-strategic independence and energy union, as well as Germany’s denunciation of Russia’s proxy war in Ukraine’s Donbass region since 2014, Chinese netizens applaud Merkel’s recognition of the need to work with Russia because of Germany’s need for cheap energy. Appeasing Russia after February 24 is off the table for the West, but Chinese netizens seem to think it is still a better move for domestic stability, regardless of the war.

Some pro-Russia Chinese netizens see the U.S. profiteering from global conflicts as a manifestation of imperialist and capitalist ugliness, but Beijing’s benefit-reaping market tactics in the war, such as easing state-controlled exchange rates to make the Rouble devalue faster against the Yuan, are speculated upon positively. China’s leadership in ridding American economic dominance by way of countering American “aggression” is similarly praised. Just as in Western countries, the Chinese public views the actions of North America and Europe through the lens of their own governance system and their country’s national interest.

Our research reveals that many netizens see China as the U.S.’s next target after Russia, and that non-hostile American gestures towards China like the dropping of import tariffs are disingenuous. Aside from the war in Ukraine, the U.S.’s adherence to the ‘One China Policy’ and simultaneous dealings with Taipei are cited as examples of the shortsightedness and hypocrisy of American politics. A majority of netizens think China requires more self-determination and needs stronger financial and security capabilities to compete with the U.S. in the long term. A few vocal social media users have even taken this concept further and rallied for the redistribution of the wealth of celebrities to fund technology and military development. While fanciful, such opinions resonate closely with Beijing’s common prosperity campaign to tackle domestic inequalities by cracking down on high profit generating sectors. Paradoxically, a one-sided information flow and the lack of understanding of the strategic and operational dimensions of foreign policy contribute to this calculus that Beijing is not sanctimoniously participating in global politics in the same way as the West.

Conclusion

Despite amassing a vibrant internet culture and the largest social media market in the world, the commercial liberalization of media in China has seen the space for discussion shrink as censors touch on more and more topics that were previously not considered to be sensitive. Since the Chinese public has little exposure to multiple viewpoints regarding international affairs, and more so as content manipulation brings online discussions into closer alignment with official lines, the Chinese public has reacted hotly to sanctions imposed on Russia by the West in ways that reflect official and elite opinions pushed by authoritative media and government outlets.

The result of continuous censorship is not only that patriotic public opinion continues to proliferate, but Chinese netizens accustomed to a manipulated information space see a parallel reality from one that is seen by those outside the country. At present, online perspectives expressed by Chinese netizens illuminate Beijing’s approach to strategic issues, such as China’s goal of successfully competing with the U.S. and realizing its own vision of global security. Social media opinion on the Russia-Ukraine war sanctions suggests that China’s foreign policy enjoys substantial public backing, and that the growing vigour of Beijing’s international influence can also resonate with support for domestic policy as national stability is supreme in the eyes of the Chinese public.

Footnotes

1. Hot topics on Weibo are ranked based on the real-time search behaviour of its users; the more people click on a topic in a short period of time, the higher up this topic will get ranked, generating more views. Search volume and timeliness are factored in to calculate the ranking. Accordingly, the ranking is refreshed once every minute to capture newer hot topics.

2. The index taken from WeChat’s analytical tool is calculated to gauge a topic’s popularity and importance by aggregating hits on WeChat’s search function, video content, written content, web pages, and advertisements. While the index starts from zero, there is no specified upper limit to its number. Looking at the entire history of popularity indexes, some of the most popular keywords can have their indexes reach three billion (e.g. “Shanghai” and “COVID”).