In the past five years, there has been a “tectonic shift” in the global manufacturing landscape, with multinational corporations like Apple and others seeking to ‘de-risk’ from China — the ‘factory floor’ of the world — due to COVID-19-related disruptions and escalating U.S.-China tensions. To reduce their dependence on China for manufacturing their high-tech electronic products and components, many of these companies have embraced a ‘China plus one’ (C+1) strategy — that is, not completely abandoning China but taking active measures to reduce their exposure to risk by downsizing their presence in the country. For instance, more than 90 per cent of North American manufacturers surveyed by Boston Consulting Group in 2023 had shifted some or all their production away from China, with Mexico, Thailand, and Vietnam emerging as new production destinations.

For a variety of reasons, India is also becoming an attractive choice for many companies. These reasons include the country’s large domestic market and abundance of labour; government policies and reforms to attract foreign direct investment (FDI); and the sheer size of its economy, which allows for investments in incentives and subsidies, research and development, and infrastructure building. The size of the economy also acts as a magnet in attracting foreign investment from multinational companies looking to benefit from India’s vast domestic market. In 2022, for example, Apple decided to expand its manufacturing base in India to reduce production lag on its iPhone 14. Foxconn, the main manufacturer of Apple’s iPhones, has since set up assembly units in the state of Karnataka.

However, despite India’s potential as a manufacturing destination, several challenges persist due to the country’s shortcomings in ‘ease of doing business’ metrics, infrastructure and supply chain issues, and the country’s late entry into the tech manufacturing landscape.

India’s strengths as a tech manufacturing hub

Rapid economic growth and a large domestic market: Thanks to its population of 1.4 billion and status as the world’s fastest-growing large economy, India is on track to become the world’s third-largest economy by 2030. As such, its market demand for electronic products is expected to grow considerably, making it an attractive destination for companies looking for a ready market for their manufactured products. A report published by Morgan Stanley predicts that India’s domestic market for electronic products will be driven by sustained consumer demand and will reach US$92 billion by 2032.

Skilled labour force: India has the world’s largest pool of English-speaking graduates in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) degrees and a low dependency ratio — that is, the ratio of young people (ages 0–19) to seniors (over 65) — of 31.2 per cent, thus providing a steady and vast supply of labour. Ernst and Young predicts that India’s working-age population will reach a peak of 68.9 per cent by 2030.

However, despite having an abundance of young workers, India still has a dearth of skilled and semi-skilled workers and inadequate vocational training opportunities. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government in recent years has sought to address this gap by launching a range of skill-development programs and vocational training centres under its Skill India Mission. While the government in 2024 claimed that the Mission has trained 14 million young people and ‘upskilled’ or re-skilled 5.4 million people, it is unclear whether these measures have led to an increase in tech-manufacturing output.

Economic reforms and government policies: Modi’s government has introduced a variety of reforms to transform India’s economic landscape. Its flagship ‘Make in India’ initiative and call for an Atmanirbhar Bharat (i.e. “a self-reliant India”) seek to boost the country’s production capabilities. This suggests diversifying away from a lopsided reliance on the services sector, which has been led thus far by information technology companies. In addition, efforts to usher in a digital revolution have prompted a significant shift from a paper currency-based economy to a digital one, which also helps in expanding markets and facilitating supply-chain connectivity.

Against the backdrop of these broad-based economic reforms, certain sector-specific policies have also been rolled out. For instance, the government’s strategic focus on semiconductor and smartphone manufacturing has been buoyed by the following measures:

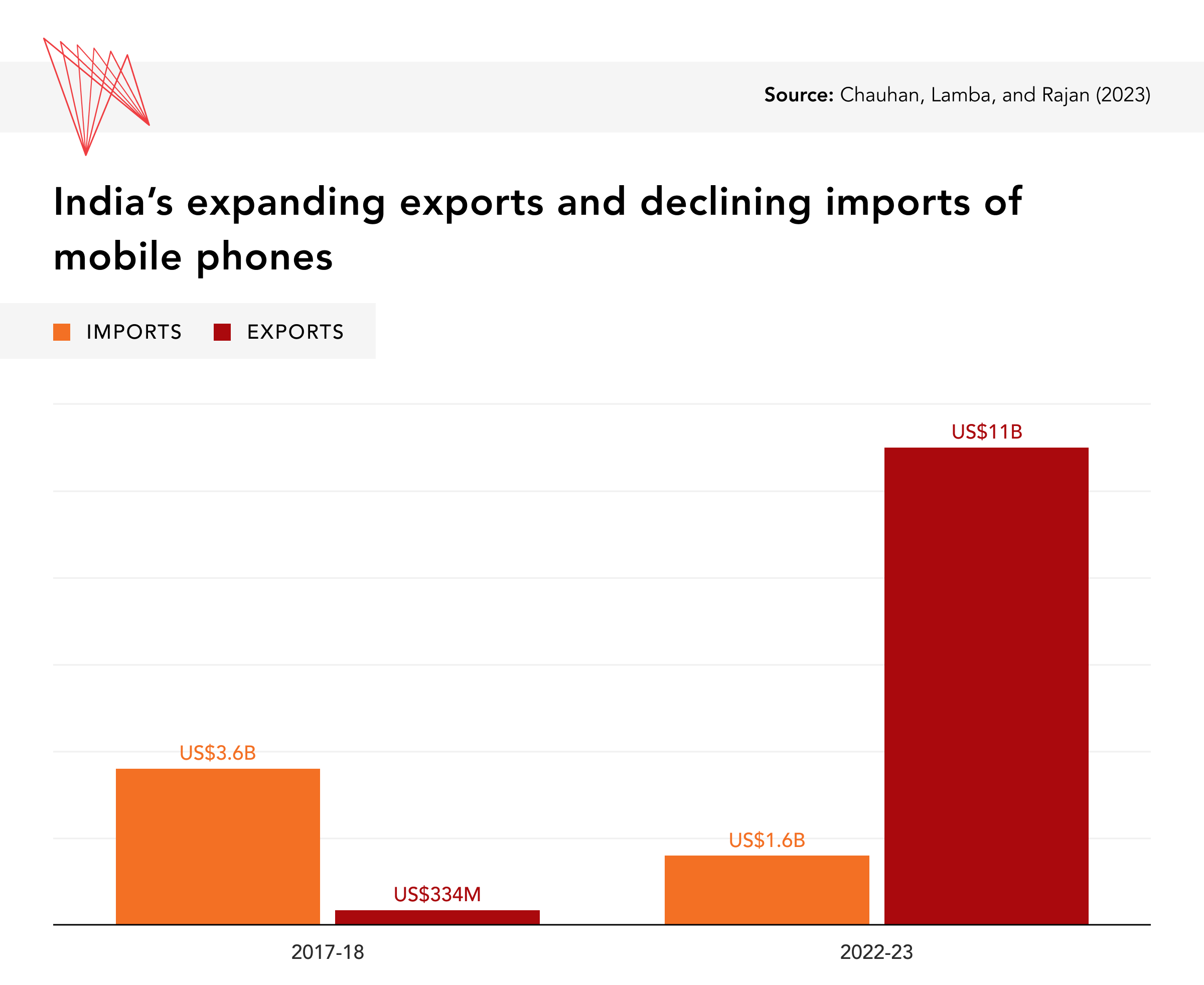

- In 2016, the Indian government raised tariffs on imports of mobile phone parts; by 2018, a 20 per cent tariff had been imposed on importing entire mobile phone units — a protectionist measure to push domestic production.

- Starting in 2020, the government’s Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme has given both Indian and foreign smartphone manufacturers a six per cent cashback on a phone’s invoice price — the price that retailers pay to the manufacturer — for incremental production targets achieved by the manufacturer. After five years, the cashback amount is reduced to four per cent. This incentive to manufacturers seeks to bolster domestic production and sustain the flow of private capital (domestic and foreign) into the industry. Moreover, state governments have offered tax incentives, energy, and land subsidies for basing production units in their state.

- The India Semiconductor Mission, launched in 2021, is an incentive scheme valued at roughly US$10 billion that seeks to attract private investment. According to this scheme, the government will provide 50 per cent of a plant’s capital expenditure costs as a subsidy. State governments like Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, and Gujarat have also introduced their own semiconductor initiatives to attract foreign investments.

Expanding FDI inflows: As a reflection of the government’s proactive policies to remove barriers to foreign investment, India now boasts impressive FDI inflows, receiving a record US$83.57 billion in FDI in 2021-22, a substantial increase from the US$60.22 billion it received in 2016-17.

Especially notable is the case of electronics manufacturing. The sector drew US$27.38 billion in 2021-22. Samsung, Pegatron, Rising Star, and Wistron have all announced significant investments. This momentum continued in 2023, evidenced by Foxconn’s historic pledge to invest US$100 billion in India.

Sector in Focus: Mobile phones

- Media reports suggest that India has blocked, allegedly with U.S. support, imports of Chinese-made smartphones by companies such as Xiaomi in a bid to boost its domestic production. In 2023, 99.2 per cent of all mobile phones sold in India were manufactured locally.

- India is expected to contribute 20 per cent of the global production of smartphones by 2032.

- The Indian conglomerate Tata Group’s recent deal with Taiwanese Wistron Corp is set to result in the country’s inaugural manufacturing unit for producing Apple’s smartphones.

- Apple plans to produce a quarter of its iPhones from India by 2030.

Sector in Focus: Semiconductors

- India’s first semiconductor fabrication plant will be set up in Gujarat’s Dholera by the Tata Group in partnership with Taiwan-based Powerchip (PSMC). With an annual production target of three billion chips, the plant will cater to the high-performance computing industry, electric vehicles, and consumer electronics.

- The Tata Group will also set up a chip assembly plant in Assam, mainly catering to the automobile market. A third chip packaging facility in Sanand in Gujarat will be set up by CG Power in partnership with Japan’s Renesas Electronics.

- U.S.-based semiconductor companies Micron, AMD, and Applied Materials have announced significant investments in India. Other foreign players seeking to invest in India’s semiconductor sector include Singapore-based IGSS Ventures and Israel’s Tower Semiconductor Ltd.

India’s challenges in becoming a ‘C+1’

Despite the domestic economic reforms described above and a geopolitical environment in which India — the world’s largest democracy — tends to be viewed in the West as a natural partner, several factors continue to impede the country’s global competitiveness. Foreign corporations have traditionally complained about bureaucratic hurdles, ease of doing business, and financial instability in India. For example, despite a US$19.5-billion partnership announcement in 2022 to set up a semiconductor unit in Gujarat, Foxconn split from its Indian counterpart, Vedanta, a year later, apparently due to the latter's financial troubles. It will now be partnering with another Indian firm, HCL, to set up a chip-testing facility in India.

Stiff competition: India is a late entrant into the global arena of hi-tech products like chips, where economies like Taiwan and South Korea have led for years. Moreover, others like Malaysia have also gotten a head start in the chip manufacturing race. While India offers a large market, inexpensive labour, and a bigger economy capable of investing in subsidies and technological innovation, the early-mover advantage and the technological advancements made by some of its Asian rivals undermine India’s competitiveness. Per Business Environment Rankings, India ranked 10th in the 2023-27 forecast period among the 17 Asian economies studied. Media reports in 2024 revealed that Singapore is proposing to offer land, water, labour, and energy subsidies along with subsidies and tax incentives for Taiwan-based Vanguard International Semiconductor to attract a production facility. Many governments are thus vying to acquire a “post-China” status in tech manufacturing.

Resource, supply chain, and infrastructure challenges: India needs to import about 85 per cent of raw materials, including critical minerals, to manufacture items such as smartphones and chips. It is not party to trade arrangements like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership or the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, both of which could provide a more reliable supply of raw materials and lower the cost of imports. Despite India’s membership in the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) supply-chains pillar, some of these concerns may endure. The IPEF has also hit early roadblocks as negotiations on its trade pillar faced opposition within the U.S., endangering the broader framework.

India also must go a long way in ensuring a supply of critical resources for semiconductor fabricators like clean water. Other issues, such as frequent power blackouts at factories and domestic supply chain and connectivity issues due to poor road infrastructure in some areas, add to the logistical challenges.

Component assembly and continued dependence on China: India’s smartphone manufacturing industry is dominated by component assembly, or the assembling of parts like display screens, cameras, battery packs, and so on, to build a complete phone unit. Experts warn that this singular focus on assembling parts — a process that relies on importing components — defeats the purpose of establishing a manufacturing hub. In addition, rare minerals, and electronic components such as integrated circuits and display panels that are required in the assembly process, often continue to be imported from China, lessening foreign companies’ ability to reduce their dependence on that country.

Shortcomings in regulatory frameworks: Concerns about labour unrest and the environment can also create hurdles. For instance, in 2023, the government of Tamil Nadu, one of India’s most business-friendly states, received backlash from trade unions for introducing a bill to extend working hours from eight to 12 to boost the production capacity of companies like Foxconn. Environmental concerns such as sustainable resource use, waste management, and pollution control affect not only the local population but also contribute to operational difficulties for multinationals that set up factories in the country.

What does India’s changing manufacturing landscape mean for Canada?

The Canadian semiconductor ecosystem boasts more than 100 domestic and multinational companies that lead research and development on chips. In 2022, Ottawa announced a C$240-million investment into its homegrown semiconductor industry and reiterated the need to work with global partners for supply chain security. Canada’s Semiconductor Council is advocating to the federal government to create a Strategic Semiconductor Consortium to foster collaboration among Canada’s semiconductor companies and enhance research and development opportunities to boost the country’s credibility in the global semiconductor space. Canadian companies and investors looking to enter Indian markets would thus benefit from keeping a close eye on the recent developments in India’s manufacturing sector boom.

In September 2023, Indian Minister for Coal and Mines Pralhad Joshi held discussions with Yukon Premier Ranj Pillai about the opportunities for strengthening the critical minerals supply chain amid rising diplomatic tensions between Canada and India. Although talks to negotiate a bilateral free trade agreement have been put on hold, the Canadian critical minerals sector could explore an export market in India, where demand from the manufacturing industry is growing. Collaborative partnerships between Canada and India could help both countries in leveraging their potential, complement their respective capacities, and enhance global supply chain resilience. The U.S.-led Minerals Security Partnership, a collaboration between 14 countries and the EU, includes Canada and India and aims to develop a robust supply chain of critical minerals. It can also open room for co-operation between the two countries for sharing resources critical to the development of tech products.

India's steadily evolving economic landscape presents a compelling opportunity for foreign companies — including Canadian companies — pursuing a ‘China plus one’ approach. With favourable government policies, a flourishing consumer market, and a large workforce, the country shows remarkable potential. Despite being wooed by global tech giants, it is, however, one among many alternative production bases being explored. The competition from other manufacturing hubs continues to be fierce. As a result, it remains to be seen whether India’s impressive targets can translate to a rise in production in ways that allow companies to de-risk away from China.