The Takeaway

India’s massive national election, which returned Prime Minister Narendra Modi to a historic third consecutive term in power, albeit with a weakened mandate, shone a light on the rising use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools to alter the nature of political campaigns and amplify voter engagement. While the technology enables parties to widen their outreach to more voters, it also raises concerns about its misuse to spread disinformation — a concern prompted by a surge in AI-generated synthetic media known as ‘deepfakes.’ AI’s impact on the Indian election is noteworthy not only because it is the world’s largest democracy, but also because it could foreshadow the challenges other democracies, including Canada, could face.

In Brief

- Many candidates in India’s recent election have used AI-powered ‘avatars’ to engage with individual citizens in an electorate with 968 million registered voters. Such “hyper-personalized” engagement is believed to enhance candidates’ political appeal by showing voters that the candidates are attuned to each voter’s specific concerns.

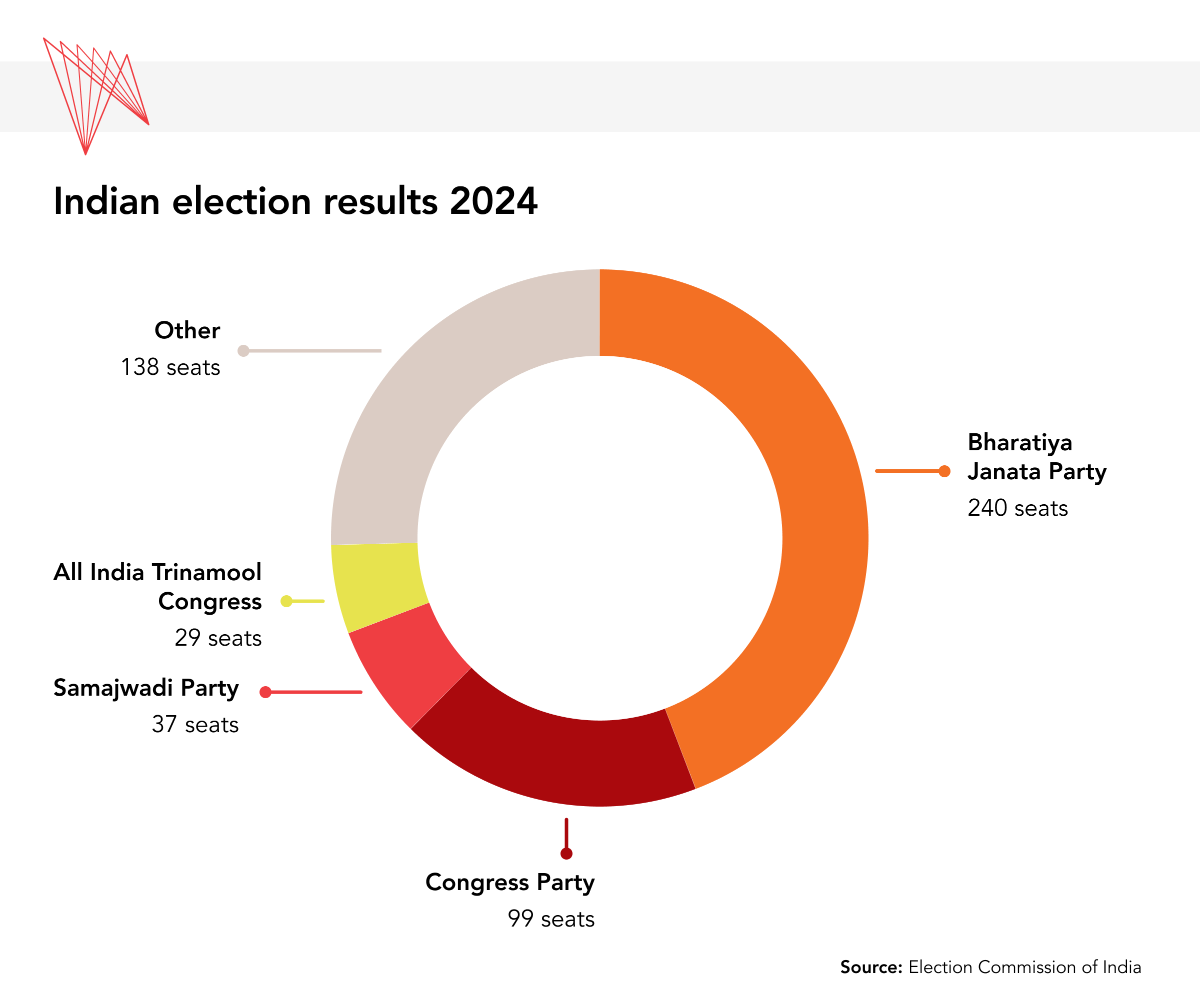

- However, the two biggest national-level parties — the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the opposition Congress Party — accused each other of unfairly influencing voters by spreading ‘fake news’ through ‘deepfakes,’ or digitally manipulated audio, images, or video.

- Recent examples include fake videos of the deceased former Tamil Nadu chief minister, M. Karunanidhi, praising the leadership of his son M.K. Stalin, the state’s current chief minister. A few Bollywood celebrities have filed police complaints about their “presence” in viral ‘deepfake’ videos circulating on social media. These videos routinely feature misleading electoral messaging.

- Meta, the parent company of WhatsApp and Facebook, reportedly approved 14 AI-generated electoral ads that contained Hindu supremacist language and called for the killing of Muslims and a key opposition leader while elections were underway. Some of the videos contained the false claim that the leader “wanted to erase Hindus from India.”

- While India’s Election Commission issued an advisory to parties on May 6 warning against AI-generated deepfakes, the government’s generally hands-off approach to regulating the AI landscape extends to its possible misuse in elections.

Implications

AI bots may not be well-versed in local dialects and are susceptible to inaccurate translations, but they can help mitigate linguistic barriers by allowing candidates to reach more voters who speak one of India’s many regional languages. This may increase support for parties like the BJP, generally seen as a party of Hindi speakers, among voters in the south and the east who do not speak Hindi. Modi, for instance, used Bhashini, the government’s AI-powered tool, to ensure that Tamil-speaking audiences could hear his speech, which was delivered in Hindi and translated into Tamil in real-time. His speeches have also been translated into Kannada, Bengali, Telugu, Odia, and Malayalam, among other languages, using AI. Additionally, prior to the election, the prime minister’s official app — NaMo — launched a feature designed to promote the government’s policy successes more widely through AI-powered chatbots.

Fears about misinformation and disinformation tainting the democratic process are especially significant in India, where social media and internet usage are widespread. The country has more than 400 million WhatsApp users – the world’s largest user base of the messaging app – and roughly 820 million active internet users. More than half of these internet users are based in rural areas, where awareness of and the ability to spot deepfakes tends to be even weaker.

Although firms such as Meta publicly pledged to block manipulative AI-generated content from spreading during the election, such content swept through social media and messaging apps. While concerns over manipulative AI content are not particularly new, with the advent of sophisticated AI tools, manipulated content may look remarkably real.

What’s Next

1. Growing demand for regulatory frameworks?

On March 1, India’s Information Technology (IT) ministry announced a requirement for tech firms to obtain government permission before making their AI products available online. This requirement came in response to the backlash against ‘Gemini,’ Google’s AI-powered chatbot, for its controversial response when asked whether Modi’s policies were “fascist.” While the ministry’s directive prompted concerns about government interference and the stifling of AI innovation, the government retracted the requirement through another directive on March 15.

The legal validity of both directives has come under scrutiny since both lacked statutory force and clarity about their scope and effect. Both directives warn against using AI models that “threaten the integrity of the electoral process,” although the criteria for determining such threats were unclear. Currently, India has no specific laws or regulations directly governing AI. In line with the Indian government’s generally hands-off approach to regulating the AI landscape, IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw informed India’s parliament in 2023 that the government was not planning to legislate on the matter or regulate the growth of AI. Nevertheless, the surge in deepfakes during elections may heighten the demand for more regulation.

2. Global challenges, Canadian concerns

While there is no reliable data yet on whether AI tools are disrupting the integrity of democratic processes, India's election may portend future trends, especially given its size, scale, and digital exposure. Canada, though ranked first among 80 countries in a 2023 report on Artificial Intelligence and Democratic Values, is not immune to the “catastrophic risk” to “democracy and geopolitical stability” posed by deepfakes and disinformation campaigns. India's experience could serve as a valuable case study for Canada as it prepares for its next federal election.

• Edited by: Erin Williams, Senior Program Manager, and Ted Fraser, Senior Editor, APF Canada