As the 2023 Association for Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit concluded in Jakarta, Indonesia, in early September, Southeast Asian leaders “strongly condemned” the continuing violence against civilians in Myanmar, one of ASEAN’s member states. In a 19-point statement, leaders called on the Myanmar Armed Forces to reduce violence and cease deliberate attacks on civilians, residences, and essential public infrastructure. One of the most visible examples of such violence carried out by the Myanmar military pre-dates the current civil war: the persecution of the Rohingya, a majority-Muslim ethnic group, many of them from Rakhine State in the west.

Since 2018, Canada has committed to assisting Rohingya refugees. That commitment is reflected in a 2018 report by former Ambassador Bob Rae — now Canada's ambassador and permanent representative to the UN — who was dispatched by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to Myanmar in 2017 as a special envoy to assess the extent of the humanitarian crisis and advise on a Canadian response. Canada’s strategy to respond to the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar and Bangladesh (2018 to 2021), which is now in its second phase (2021 to 2024), includes humanitarian assistance to Rohingya refugees displaced to Bangladesh, with a focus on providing health care and education. It also commits to providing resettlement in Canada for members of this population through Canada’s Refugee and Humanitarian Resettlement Program, in collaboration with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and private sponsors.

There appears to be a disparity in the Canadian resettlement of people fleeing violent conflicts worldwide. For example, in February 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine, Canada promptly enacted the Canada-Ukraine Authorization for Emergency Travel program, allowing an unlimited number of Ukrainians fleeing the war to work, study, and stay in Canada for up to three years. Since 2022, more than 175,729 Ukrainian nationals have arrived. In contrast, as of 2020, only 44,620 Syrian refugees have entered Canada since the beginning of the Syrian refugee crisis in 2011, and only 36,690 Afghan nationals have been resettled since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021. The number of Rohingya refugees resettled in Canada is far lower: only 1,000 since 2006. This imbalance is striking.

The Rohingya are living on borrowed time; conditions in the camps that house them in Bangladesh are deteriorating, and fears of re-victimization are surfacing, especially as Bangladesh and Myanmar pilot a problematic repatriation project. It is, therefore, worth asking why Canada’s resettlement plan is not adequately addressing the urgency and plight of the Rohingya.

The making of a crisis

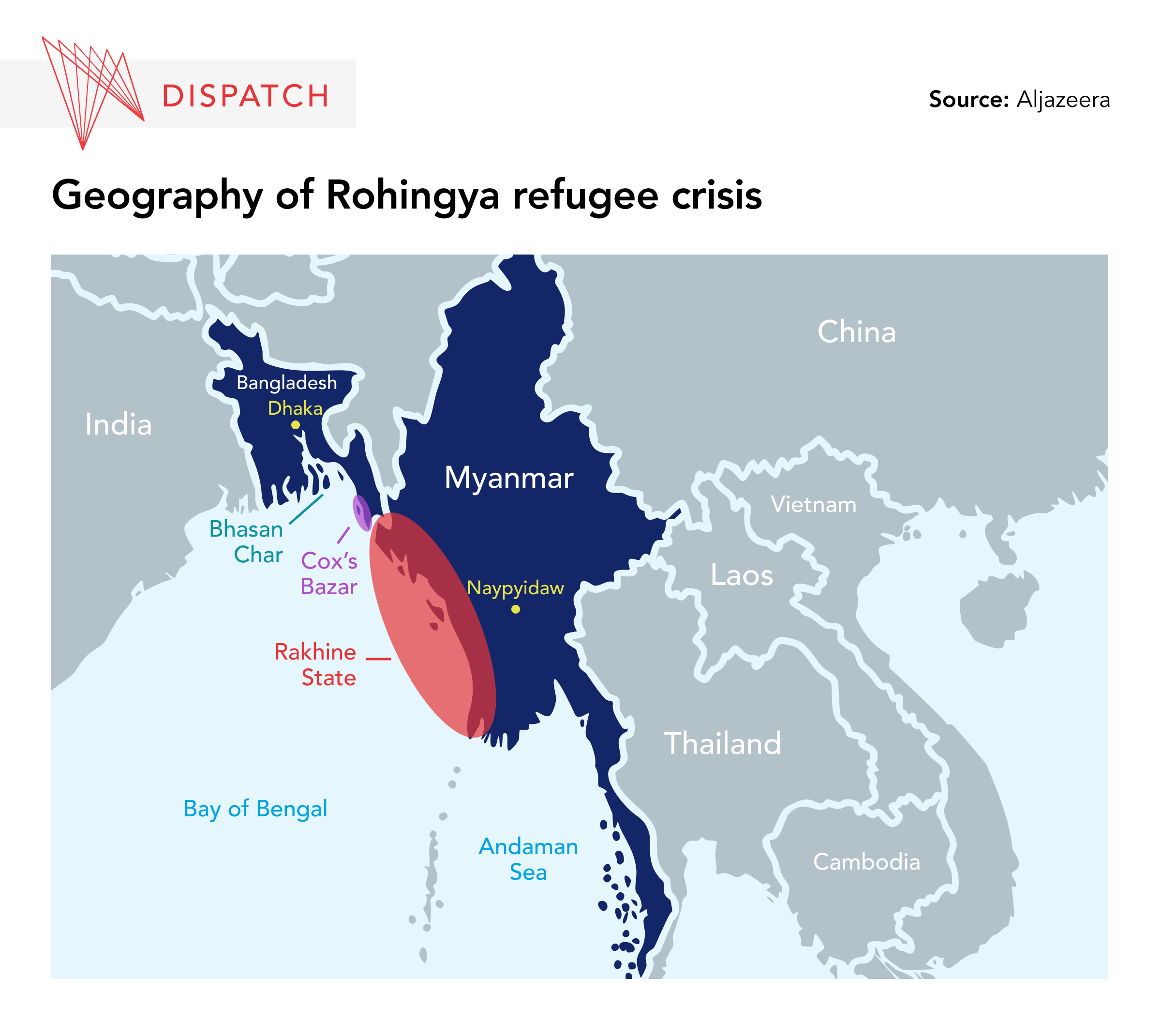

The mass exodus of Rohingya from Myanmar became a humanitarian crisis in 2017 when approximately 700,000 Rohingya refugees crossed into neighbouring Bangladesh after the Myanmar military launched a full-scale ethnic cleansing drive that began in 2016. The Rohingya ruled northern Arakan (now called Rakhine State) from the 12th century until the king of Burma (now Myanmar) defeated them in 1784. The Rohingya subsequently wanted to cede from Burma, as they were subjected to systematic discrimination and targeted violence from the Buddhist-majority Rakhine people over ethnic and religious differences. In 1982, the Rohingya were stripped of their citizenship when Myanmar’s military dictatorship enacted a controversial law that failed to recognize them as one of its 135 national races, categorizing them as “illegal immigrants” who arrived during the British colonial era. The Myanmar military led multiple attacks on the Rohingya in the latter half of the 20th century, forcing many to flee to neighbouring Bangladesh, even before the onset of the 2017 crisis. Almost one million stateless Rohingya now reside in overcrowded camps in Cox’s Bazar in southeastern Bangladesh, barely surviving on a dwindling supply of humanitarian assistance.

Facing a plethora of perilous options

Although other global events have largely eclipsed international attention to the Rohingya refugee crisis, the situation has been anything but static. Several factors – in Bangladesh, Myanmar, and internationally – are making the Rohingyas’ safety and survival less tenable. For example:

- Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Bangladesh has requested the international community’s support in repatriating the Rohingya refugees. Hosting approximately one million Rohingya has strained Bangladesh's economy, which is struggling with inflation, an energy crisis, and plunging foreign exchange reserves. In September 2022, during a meeting of the UN General Assembly, Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina urged world leaders to support repatriation, urging “the UN and other partners to assist Myanmar to create necessary conditions for safe and dignified repatriation.”

- Major donors, including the U.S., the U.K., and the European Commission, have cut their funding amid the global economic downturn, which has been exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine war. These cuts disrupted the delivery of basic services in the first half of 2023, including a 33 per cent reduction in food rations, previously set at a meagre C$16.00 per person per month. Bangladesh needs C$1.2 billion annually to support the Rohingya, but currently is getting less than half that amount from donors.

- Meanwhile, the Rohingya continue to live in congested camps without health care or the means to earn a living, where they are exposed to natural disasters, crime, and frequent fires — some resulting from arson.

Refugees gather at beach in Cox's Bazar on May 12, 2023, ahead of the landfall of cyclone Mocha that struck the low-lying area in the Bay of Bengal. | Photo: Munir uz zaman/AFP via Getty Images - Since December 2020, Bangladesh has relocated more than 30,000 Rohingya to Bhasan Char, a silt island in the Bay of Bengal, to alleviate congestion in the Cox's Bazar camps. The decision has been criticized by international observers as “refugee warehousing,” as it restricts their mobility and freedom and keeps them dependent on the host country indefinitely. The low-lying island is highly prone to climate change-induced natural disasters, and concerns have been raised about the safety of the Rohingya living there. In March, Bangladesh submitted two proposals to foreign diplomats and representatives stationed in Dhaka, seeking the international community’s help to relocate another 70,000 Rohingya to the island.

- A sense of growing vulnerability and desperation in both Bangladesh and Myanmar has prompted some Rohingya to try to cross the Andaman Sea by boat in hopes of reaching Malaysia or Indonesia, even though the conditions for doing so are extremely precarious. In December 2022, the UN Refugee Agency warned about the sharp rise in attempted crossings. In 2022, 1,920 people, mostly Rohingya, travelled using this route, with at least 119 people reported dead or missing.

- As noted above, Myanmar is gearing up to repatriate 711 Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh after a long hiatus since it signed a repatriation agreement with Bangladesh in 2018. Political observers attribute Myanmar’s sudden interest in welcoming back Rohingya to ASEAN’s pressure to restore regional stability and China’s mediation efforts between Naypyidaw and Dhaka. As Myanmar delays discussing crucial issues, including citizenship and security for the Rohingya ahead of the planned repatriation, the community fears re-victimization.

The worsening plight of the Rohingya community requires immediate and more proactive intervention by the international community to ensure their safe resettlement. That includes Canada making good on the commitments it made in its Rohingya strategy.

Canadian assistance

In his 2018 report, Bob Rae emphasized the role that Canada could play in providing refuge to the Rohingya and imposing economic sanctions against those responsible for the crisis. Ottawa has followed through on the second of these recommendations – it was a significant behind-the-scenes player in bringing the Myanmar government to the International Court of Justice in 2019 to face charges of genocide against the Rohingya. But what about the first commitment to provide refuge?

The Canadian government has laid the foundation for the Rohingyas’ integration into Canadian society through various refugee resettlement programs and schemes. One scheme for which the stateless Rohingya in Bangladesh qualify is Canada’s Refugee and Humanitarian Resettlement Program for people needing protection outside Canada. The Bangladesh office of the UNHCR and private sponsors shortlist refugees for resettlement. Under the resettlement program, Canada then selects refugees to admit by applying its criteria to the applications of those referred by the UNHCR (i.e. a person cannot apply directly to Canada for resettlement). Usually, the most vulnerable refugees, such as those who have received death threats, are referred by the UNHCR. For instance, the family members of Rohingya activist Mohib Ullah, who was shot dead by a group of armed men who were also Rohingya refugees, were relocated to Canada in March 2022.

Following Rae’s recommendations, in offering the Rohingya refuge, Canada is not only providing them with safety and the basic right to live, but through equal opportunities in education, employment, and health care, would give them the opportunity to integrate into Canada as citizens and productive members of society. This should not be viewed as simply an act of charity on Canada’s part. As Prime Minister Justin Trudeau noted on July 8 during a speech at the Calgary Stampede in reference to contributions by the Ismaili community, members of which settled in major Canadian cities, including Calgary, starting 50 years ago as refugees from Uganda, after being politically ostracized by dictator Idi Amin: "When we welcome in refugees, we are not only giving them opportunities. We are enriching our country so deeply from everything this community has done in Canada." Canada, renowned for providing safety and opportunities to communities in distress, can similarly give the Rohingya a chance to survive and thrive.

Reviewing Canada's Rohingya approach

In his book Myanmar's Enemy Within: Buddhist Violence and the Making of a Muslim 'Other,' Francis Wade discusses the lack of co-ordination within, and insufficient services provided by, the international organizations that are present in Cox’s Bazar, including the United Nations, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières). Since humanitarian organizations alone have been unable to tackle such organizational issues, the Government of Canada did collaborate with The United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, or UN Women, in creating the Gender Hub in March 2019 to provide better technical assistance and capacity development initiatives in the camp. The Gender Hub supports local organizations and governments in devising, organizing, and carrying out their humanitarian work, with a focus on attaining greater gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls in the Rohingya refugee camps.

An expansion of intergovernmental collaboration, currently inadequate and inefficient, could assist Canada in the second phase of its Rohingya strategy. The last meeting minutes from the Gender in Humanitarian Action Group set up under the Gender Hub show how there are many humanitarian and development organizations involved as members, but there is very little intergovernmental collaboration. With Canada’s expanded presence in the Indo-Pacific region, there may be an emerging opportunity for intergovernmental collaboration with ASEAN member states to recalibrate a regional response to the crisis while actively invoking the 19-point statement as Dhaka continually seeks help from global leaders in finding a permanent solution.

Beyond the frontlines of the refugee crisis in Bangladesh, a lack of international collaboration has also been a major factor in Canada’s refugee resettlement program. In 2006, Canada became the first country to resettle Rohingya from Bangladesh, but, as noted above, it has resettled only a small number. One of the biggest roadblocks is government bureaucracy across stakeholder countries. Even though the UNHCR, along with the UN International Organization for Migrants, has strived to resettle refugees in Bangladesh, in 2017, then Canadian Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen claimed that, since 2009, Bangladesh has denied most Rohingya an “exit visa.” The reason for this denial is generally believed to be a fear by Dhaka that more Rohingya will enter the country if they expect to be resettled in a third country. For the most part, Dhaka has granted these exit visas only on an ad hoc basis, such as when a refugee faces targeted threats (which was the case with Mohib Ullah’s family) or requires urgent medical attention.

While the issue of Bangladesh refusing to issue exit visas remains a roadblock to Rohingya resettlement, the U.S. began the process of resettling 62 Rohingya from Cox’s Bazar in December 2022, of which 24 have left Bangladesh for the U.S. There is little conclusive and publicly available evidence as to why the U.S. managed to secure exit visas for these 64 refugees, but it nonetheless creates a possible pretext for the Canadian High Commission in Dhaka to follow suit.

Strategizing a new approach

The Rohingya rightfully fear continued persecution, not only if they are returned to Myanmar but also if they must remain in Bangladesh. Now is the time for Canada to seek intergovernmental support, form international alliances, resettle refugees, and re-strategize its response to the Rohingya refugee crisis.

At a minimum, Canada’s High Commission in Dhaka could consult with the U.S. government and other stakeholder governments about pushing through bureaucratic hurdles. Canada could also establish another special envoy position; this one focused specifically on oversight of a new resettlement campaign for the Rohingya languishing in Bangladesh. As the Rohingyas’ desperation mounts, given their precarious position in Bangladesh, internal camp violence, and funding shortfalls, the clock is ticking for Canada to provide durable resettlement opportunities for the Rohingya and ensure they become equal, self-reliant citizens of the world.