To those who have been keeping an eye on China’s air pollution problems, results of the “Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan” (大气污染防治行动计划), also known as the “Ten Measures for Air,” were quite encouraging. Since the policy’s enforcement in 2013, significant improvements have been seen in areas like reducing the concentration of fine particles (PM2.5), with all three major city clusters around Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou meeting ambitious targets by the end of 2017. [1]

Xi’an’s persistent air problems

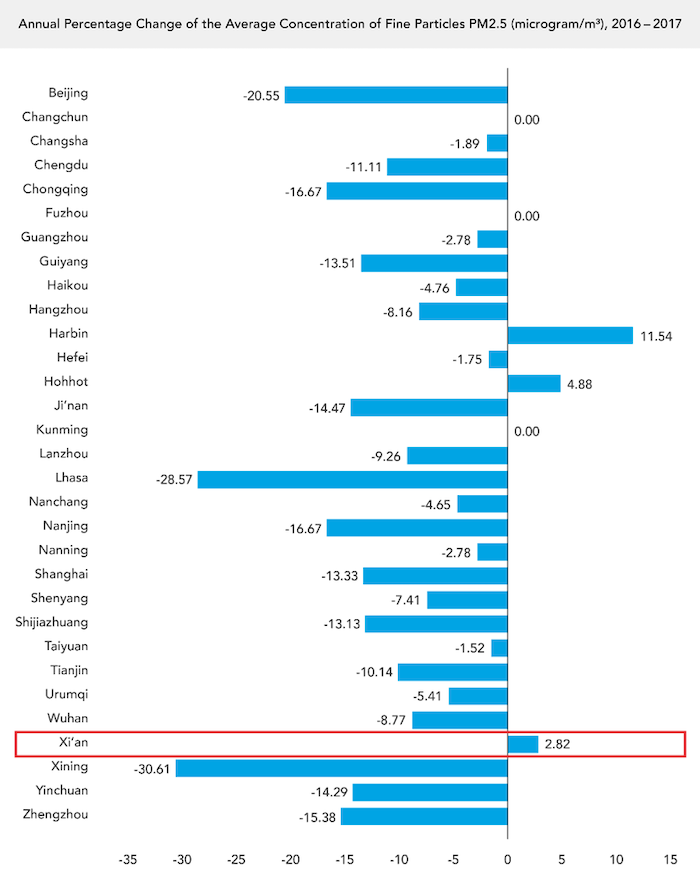

Falling outside of the plan’s key focused geographical areas, Xi’an City, capital of China’s northwestern Shaanxi Province, began to attract more attention in recent years with its notorious air quality records. In 2016, Xi’an experienced the largest year-over-year percentage increases in both the annual percentage of days with polluted air quality (by 50.87 percent) and the average concentration of PM2.5 (by 22.41 percent) among the country’s 31 provincial capitals. PM2.5 pollution in the city again stood out in 2017 as the yearly average reached 73 microgram/m³ – more than seven times the 10 microgram/m³ “safe” level set by the World Health Organization and the second highest among all Chinese capital cities in that year. In fact, Xi’an was one of only three provincial capitals that witnessed increased PM2.5 concentration in 2017 compared to the previous year, while the other 28 capital cities all managed to, to different extents, lower their figures during the same period.

A tough battleground

Like many cities in China experiencing severe atmospheric pollution, heavy reliance on coal for both industrial and residential uses, as well as emissions from the 2.8 million vehicles on the roads, are among the major sources of fine particles and other pollutants in the air of Xi’an. However, what makes the city’s air quality problem particularly difficult to tackle is the geographical location. Xi’an sits in a basin with Loess Plateau to the north and the Qinling Mountains to the south. These surrounding mountains shelter the area from heavy rains and strong winds, leading to slow dispersion of the air pollutants. In addition, being relatively close to some of China’s largest desert regions means air quality in Xi’an is often adversely affected by sandstorms, further exacerbating its problem.

In addition to the unfavourable natural conditions, the lack of effective air pollution management policies and execution in the past was probably equally problematic. Beijing’s relatively more successful policy enforcement between 2013 and 2017 resulted in 140,000 households switching from coal to natural gas for residential heating, which helped lower its PM2.5 concentration by an annual average of almost 10 percent during the period. In contrast, the government of Xi’an struggled with an insufficient supply of gas as well as inadequate gas-transporting infrastructure. As a result, even though the coal-to-gas conversion rate (135,000 households between 2013 and 2016) is in theory at a similar level as Beijing’s, there was in practice continuous reliance on coal for heating during winter, particularly in rural households.

What’s more crucial is the fact that reduction of industrial coal combustion is to this date mainly realized through switching off coal-fired boilers – this method is approaching its limit since it does not fundamentally change the coal-based energy structure. Moreover, unpermitted and fugitive dust emissions remain to be rampant in Xi’an and its neighbouring cities. On the enforcement front, scandals such as local officials obstructing the work of air quality monitoring equipment in an attempt to tamper with the emission readings further underscore the administrative loopholes in the city’s pollution-combatting operations.

New phase, new hope?

Realizing the pressing need to effectively tackle the environmental issues in cities like Xi’an that are outside of the previously targeted regions, the Chinese central government identified the Fen-Wei Plain (which spans the provinces of Shaanxi, Henan, and Shanxi) as a new focal point of air pollution control. This is part of the “2018-2020 Three-Year Action Plan for Winning the Blue Sky War” (打赢蓝天保卫战三年行动计划), the policy document that is widely regarded as the second phase of the “Ten Measures for Air.”

Heavy smog engulfs the ancient city of Xi'an, China in 2013, the result of persistent industrial coal combustion and the proliferation of internal combustion engines. This image reflects the city prior to co-ordinated policy efforts to tackle Xi'an's atmospheric pollution that began in earnest last year. | Photo by VCG/VCG via Getty Images

Within the wider framework of industrial, energy, transport, and land-use structure adjustments, specific measures were introduced to address the challenges faced by Xi’an and other cities in the Fen-Wei Plain region in their past air pollution management efforts. For instance, in view of the inadequate gas supply that stagnated effective coal-to-gas conversion, the new action plan allows for more flexibility in choosing which form of cleaner energy to convert to. It also promises policy and financial support to ensure that these alternative energy solutions are affordable for residents. Furthermore, quantified goals will have to be met regarding the elimination of the region’s main sources of pollution, including capping the total coal consumption, increasing the proportion of railway freight transport (which is more environmentally friendly), eliminating diesel-powered trucks, and controlling construction dust.

To meet the national- and regional-level goals, Xi’an introduced a city-level operation scheme, called the “Three-Year Action Plan for Managing Haze with an Iron Fist and Defending the Blue Sky” (铁腕治霾保卫蓝天三年行动方案). It focuses on lowering the PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations by setting step-by-step yearly targets to eliminate by 2020 all high-energy-consuming and high-emitting plants, all residential use of bulk coal, and all coal-fired heat plants and boilers that have not gone through an energy-efficiency retrofit. The Xi’an municipal government also recently revised its “Regulations on the Prevention and Control of Ambient Air Pollution” (西安市大气污染防治条例) to ensure that key stakeholders – in this case, the local governments as well as the emitting industries – will be held responsible for failures in meeting the targets. Governments at municipal, district, and county levels are required to set up evaluation and accountability systems, which would link the jurisdiction’s air pollution management progress directly to the officials’ performance assessment. The emitting businesses, on the other hand, face not only stricter requirements, such as having to keep at least three years of original monitoring records, but also steeper fines of as high as C$6M (RMB¥30M) if they fail to abide by the regulations.

From challenges to co-operation – with Canada

As Xi’an was put under the spotlight in the renewed nationwide effort to improve air quality, and because the local government launched a more intensive campaign to deal with its longstanding conundrum, the city has achieved some positive results during the past year. However, progress is inconsistent and not on par with the rest of the country. The latest brief from the municipal government indicated that the 2018 goal for PM2.5 concentration was more or less met (61 microgram/m³ compared with the 60 microgram/m³ benchmark). Nonetheless, the number of days with non-polluted air quality (188 days) still fell considerably below the target of 243 days, and the city was ranked 12th worst in terms of overall air quality in 2018 among 169 key cities closely monitored across the country. Although there has been a noticeable shift of policy focus toward addressing the deeper-level structural problems, Xi’an’s current smog-combatting measures, including the attention-grabbing experiment of installing a 100-metre-tall air purification tower on the city’s outskirts, tend to either be costly or unnecessarily sacrifice economic activities. Moreover, it is still unclear how much financial support the city can get from the central government to expedite the rather pricey energy structure reform programs.

Thus, it is all the more important to look for cost-effective solutions and draw on the experience of global cleantech leaders, including many Canadian companies and organizations. In terms of setting up an effective emission control system, Xi’an could look into how Environment and Climate Change Canada devises specific instruments for each key emitting sector to reduce ozone and fine particulate matter concentrations. Likewise, Canadian companies that have the technologies to improve environmental friendliness and power efficiency in infrastructure projects and other production processes are potential business partners that Xi’an is looking for. On the other hand, Xi’an could be a great testing ground for Canadian cleantech leaders to start commercializing some of their cutting-edge innovations that have not yet been put on the market. And for those that are already on the ground, like Canadian-founded and Beijing-based air quality monitor producer Kaiterra, there lies the possibility of business expansion into a new region that may be in need of their technologies. There are plenty of opportunities for both sides to explore – and the sooner the co-operation can take place, the greater the benefit will be.