In May, North Korea test-fired an intermediate-range ballistic missile – the so-called Hwasong-12 – that landed in the Sea of Japan. This followed a series of missile tests over the past few months aimed at perfecting Pyongyang’s delivery system to match with a potential nuclear warhead. Indeed, since North Korean leader Kim Jong-un took power in 2011, the bellicose regime has made three nuclear and more than seventy missile tests. This geostrategic backdrop is changing the strategic calculus of many states in the region and Japan is no exception.

The threat from North Korea is a key example of the increasingly dynamic and threatening security environment in Asia. The election of President Donald Trump in the U.S. – and uncertainty of the U.S. role in the region – has further contributed to Asia’s changing geopolitical environment. In response to these uncertainties, Japan is taking a two-pronged approach in relation to economics and security. While it is impossible to disentangle the two, the below sections outline the main security-related responses and options as Tokyo reassesses its relationships with the region’s primary powers.

In response to Asia’s changing geopolitical environment, Japan is trying to engage major powers in the region to draw in and keep the U.S. engaged in the Asia Pacific. Tokyo is also looking to complementary partners – such as India and Australia - to offset at least some of the insecurity that could result from a sudden loss of confidence in the stability of the Japan-U.S. security alliance.

Evolving Security Posture in Japan

Since Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe took office in December 2012, Tokyo has undergone a dramatic evolution of its security architecture aimed at shoring up national defence capabilities but also enhancing the role and seamlessness of the U.S.-Japan alliance. Some highlights of the past five years include: a new National Security Council, a national-security strategy, a relaxation on arms exports to friendly countries, stronger protection of classified materials and a reinterpretation of Japan’s constitutional right to collective self-defence. Most of these initiatives serve a dual purpose: to retro-fit Japan’s antiquated security architecture and bolster the U.S.-Japan alliance which has not evolved greatly over the years because Tokyo’s “pacifist” constitution limits its role and responsibilities in defence and security matters.

Perhaps one of the most critical of these changes was the revised bilateral defence guidelines, released in April 2015, between Washington and Tokyo. Through these updated reforms, the U.S. and Japan looked to retrofit their alliance to address the region’s increasingly dynamic and threatening security environment.

US-Japan Relations in the Trump Era

The election of Donald Trump as U.S. President in November 2016 stunned Japanese policymakers and officials, even though in the months leading up to the election, Tokyo was aware of Trump’s protectionist and isolationist rhetoric. The election forced Tokyo to rapidly reanalyze its approach to Washington and proactively head-off deepening concerns about Trump’s commitment to the U.S.-Japan alliance and also his distaste for the Trans-Pacific Partnership – a major regional free trade agreement led by Washington and Tokyo that has been signed but not ratified (indeed Trump has since officially “withdrawn” the U.S. from any potential ratification).

Tokyo was also concerned about Trump’s surprising and brazen comments on the value of U.S. security alliances and burden-sharing equities between the U.S. and its allies made during the presidential election campaign. Some of these comments were directed specifically at Washington’s relations with key Asian allies, including Japan and South Korea.

Nevertheless, official visits have helped alleviate Tokyo’s concerns over alliance drift, including visits from Defense Secretary James Mattis in February, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in March and Abe’s two meetings with Trump – one in November in New York (while Trump was still President-elect) and the second this past February in Washington and Florida. Abe feels emboldened and indeed even opportunistic in his attachment to the U.S. alliance after these meetings, and was largely pleased with Trump’s strong commitments to Tokyo on security matters. During the February meeting, Trump re-iterated longstanding U.S. policy that the Senkaku Islands – part of a bitter territorial row with China – remain under the umbrella of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. The U.S.-Japan Joint Statement released following the meeting went even further on security issues with Washington leaving out any caveat on its neutrality regarding the sovereignty of the Senkakus. Similarly, for the first time in decades, the U.S. explicitly indicated via the joint statement that a range of capabilities covers Japan’s defence, including nuclear weapons. This public statement slightly soothed fears in Tokyo about potential drift in the alliance under Trump.

Despite these reassurances for Tokyo, Abe will likely remain cautious of the U.S. approach to China and likely has concerns that Beijing may try to manipulate the White House in some key areas – including maritime security and the Korean peninsula. Part of this concern is that China may try to provide Trump with a “grand bargain” that would negatively impact Japan’s security interests in the region.

Limited Hedging Options

Often states prefer to conduct their international relations through “hedging” – which simply implies they balance their interests and reliance on one relationship with others. Sometimes these other options are contradictory or opposing forces. The uncertain Trump era has been a wake-up call that has forced many traditional allies and partners of the United States to reconsider the balance of their strategic relationships. Tokyo, despite its long-standing commitment to and reliance on its alliance with Washington, is not immune to this and should take a deeper look at avenues to broaden and diversify itself from a narrow view of the U.S.-Japan alliance. That being said, to make a meaningful hedge on its relationship with the U.S., Japan needs credible strategic alternatives. At this point, none of Japan’s options to diversify are sufficient.

China:

The most obvious option in terms of a great-power hedge would be for Japan to tilt towards a stronger and more balanced relationship with China. It is tempting to look at the relationship’s future trajectory as “glass half-full.” Recent tensions in the East China Sea over the Senkaku islands (claimed by China and referred to as the Diaoyu) have gradually stabilized into a shaky status quo after tensions peaked in 2013-14. Since then, proponents of the China hedge may point to the fact the political deep-freeze between Tokyo and Beijing has gradually thawed with Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Abe having finally met on a few occasions and more regular – if still infrequent – exchange of high-level emissaries between both sides.

In addition, Tokyo and Beijing have deep interests in improving their economic relationship. A stronger partnership between the two sides could form an ultimate regional power with a combined GDP of more than US$16 trillion, nearly matching that of the United States and more than doubling that of India, Russia, Australia and ASEAN combined. The two are also wedded through interdependent economies and China is – by far - Japan’s number one trading partner. Meanwhile, Beijing relies on Tokyo as its primary source for imports.

Despite these economic linkages, security concerns make a credible hedge or tilt towards China seem out of the question in the near and medium future. While North Korea may garner most of the media attention and help Abe sell his plans for potential constitutional revision, China remains the true strategic challenge first of mind for most Tokyo policy makers. Indeed, while there has been much attention placed on destabilizing events on the Korean peninsula and in the South China Sea, there has also been a steady and incremental worsening security environment in the East China Sea. In addition to tensions over the Senkaku, Japan and China continue to trade barbs over historical issues and diverge on other key regional security touch points such as freedom of navigation in the South China Sea and the security situation in the Korean peninsula.

Trends of Chinese vessels in the waters surrounding the Senkaku (Source: Coast Guard of Japan)

Russia:

Some pundits suggest Russia might prove a positive hedging option for Japan. Indeed, Abe has invested significant capital into his relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin, with whom he has met on sixteen occasions since 2013. The political catalyst for Abe repairing ties with Moscow is to resolve the decades-old territorial row with Russia over the Southern Kuril islands (referred to as the Northern Territories in Japan). The Soviet Union seized the four disputed islands during the final days of World War II and Russia continues to administer the territory despite protests from Japan. Progress on a territorial deal has been difficult but Abe now feels emboldened to use his personal relationship with Putin to resolve the spat.

In some ways, stronger ties with Moscow make sense for Japan. An enhanced bilateral framework could increase bilateral trade, which is currently at an underwhelming level, and encourage greater foreign investment by both sides. Abe appears to be pursuing this goal through an eight-point economic plan adopted last year that prioritizes a growth in economic relations with Moscow. Japan also remains interested in developing its energy relationship with Russia to help it diversify from its overdependence on Middle Eastern energy sources. Tokyo’s nuclear energy program, which once accounted for nearly a third of its domestic energy supply, is in limbo, causing significant energy security constraints for Japan.

But, while energy and trade are appealing, the most important motivation for Abe is strategic: increasing ties with Russia could, at least theoretically, serve as a credible hedge against China’s assertiveness in the region. Essentially, Abe likely sees engaging with Russia as low risk, even with few rewards thus far, and will look for any dividend that may weaken the growing China-Russia strategic relationship. In this light, Japan and Russia recently resumed their “2+2” meeting in Tokyo – a meeting between foreign affairs and defence ministers from the two countries. (The “2+2” had been suspended for the past three years as a result of Moscow’s illegal annexation of Crimea and sustained interference in Eastern Ukraine.)

This level of exchange is typically reserved for allies and close strategic partners with a common sense of purpose on foreign policy and the international security environment. Despite this, the Abe administration agreed to resume the exchange last fall during Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Japan.

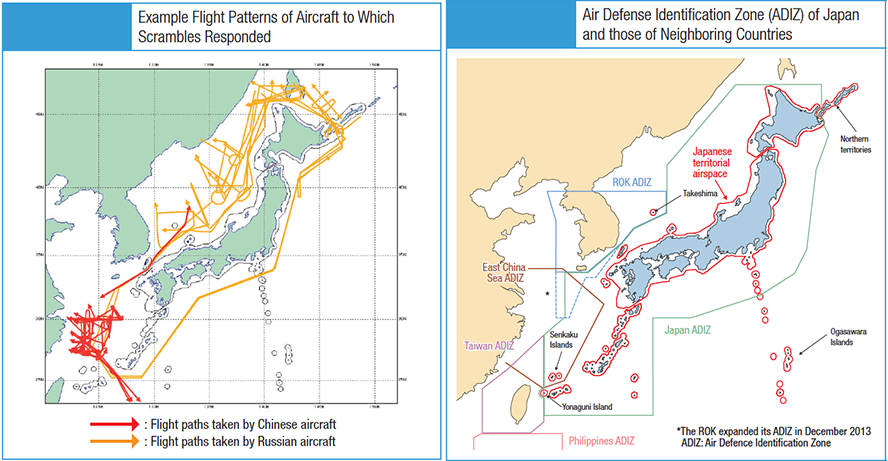

Patterns of Chinese and Russian Airspace Incursions and ADIZ (Source: Ministry of Defense, Japan)

But the credibility of a hedge with Russia is questionable. Despite Abe’s persistence on dealing with Putin, Japanese companies remain wary of investing in Russia’s Far East and fostering greater trade and investment continues to be a challenge under the current sanctions maintained by Tokyo against Moscow. Moreover, Japan’s engagement with Putin continues to be sensitive in the G7 context – with other states in the grouping opposed to Russian actions in Crimea and the Ukraine. Finally, and most importantly, it is difficult for the Abe administration to continue to downplay the destabilizing Russian activities in Europe due to the normative nexus with Chinese actions in East Asia. For example, Russia’s annexation of Crimea may be seen as a precedent for states changing the status quo through coercion – something Tokyo has warned of over Beijing’s encroachment in the East and South China Seas.

Broader US-Japan Security Network in Asia - The Complementary Hedge

As outlined above, Japan has limited “hard hedge” options in the region due to its strategic divergences with other larger powers in the region, such as China and Russia. That said, Abe has expended significant efforts over the past four years nurturing relationships with peripheral countries that can be framed as a complementary or soft hedge to the U.S. alliance. This includes the growth of longstanding and positive ties with Australia, India and Taiwan. Tokyo is also building stronger security ties with states in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and countries in the Indian Ocean Region such as Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. The most significant relationships in the framework are those with Australia and India, two states Japan recognizes as having the right combination of economic and political strength as well as a likeminded normative, rules-based and democratic approach.

More critically, Australia and India both share Japan’s concerns about China’s increasingly aggressive moves in the South China Sea and its development of infrastructure and plans for a “maritime silk road” that traverses the Indian Ocean Region. The region’s volatility underpins the need for Japan to mobilize the diplomatic capital it has amassed under Abe’s tenure to push forward the rules-based liberal order. The likelihood that Trump will not drive regional trilateral security alliances (such as the U.S.-Japan-Australia, U.S.-Japan-India, and U.S.-Japan-South Korea alliances) leaves room for Abe to take a stronger leadership role and try to keep the U.S. engaged.

While it is clear Trump will not pursue U.S. involvement in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, there is much uncertainty about the rest of his foreign policy leanings in East Asia. And, while Trump may have a preference towards bilateral alliances and a “transactional approach” to security relationships – it remains premature and unrealistic to conclude the U.S. will back out of Asia’s overlapping security networks. The stakes are too high for Washington and, while the current architecture has vulnerabilities and is imperfect, the region’s security is interlinked with U.S. prosperity and security.

Implications for Canada

Japan’s security evolution and the dynamic regional landscape must not be ignored in Canada. While the Canada-Japan relationship built on long-standing trade and personal ties, remains robust, defence and security cooperation has traditionally not been a focal point. Ten years ago, this may not have been a significant inhibitor – but as Tokyo’s regional threat perceptions change, so do its expectations of its friends and allies. To be fair, there has been some attention to this in recent years with greater focus on security dialogues, a consistent 2+2 meeting on diplomatic and defence issues, and work towards finalizing key agreements in the defence sector – such as an Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement and a General Security of Military Information Agreement.

Canada should be realistic about the extent of its contributions from both a strategic and resource perspective. Ottawa has interests in balancing its engagement in East Asia and has an economic pull to China. That said, Japan’s political-security concerns in the region should not be overlooked and Canada can regain crucial diplomatic currency – both in Japan and the broader region – by strongly advocating its principles and support for international law and peaceful dispute settlement.