Historically, Canada has not realized the full potential of trade with India, which is known to be a difficult market for exporters to enter. Both countries launched negotiations for a CEPA in 2010 before abandoning the process in 2017. But as India is now moving away from its trade protectionist tendencies and seeking to expand trade relations with new partners, the time is finally right for Canada to strike a trade deal with this South Asian country of more than 1.4 billion. On March 11, 2022, Mary Ng, Canadian Minister of International Trade, Export Promotion, Small Business, and Economic Development, and Piyush Goyal, Indian Minister of Commerce and Industry, agreed to formally resume trade talks between the two countries. Since then, both parties have engaged in multiple talks to rapidly conclude an EPTA by the end of this year, so that both countries can negotiate a CEPA by 2023.

Why Canada Needs India: Trade Diversification to Strategic Partnership

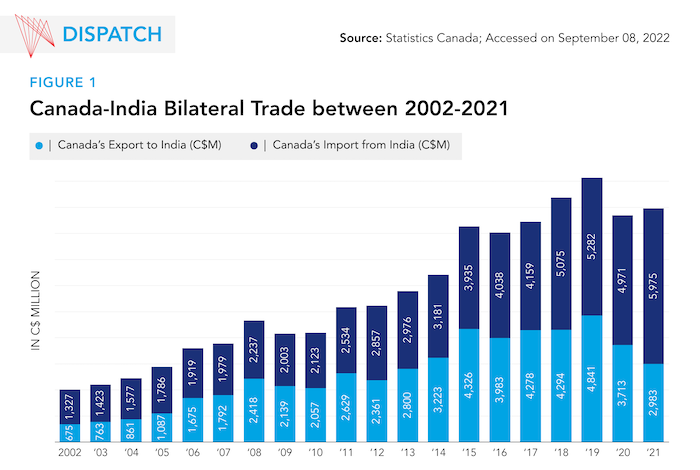

Bilateral trade between Canada and India has been growing steadily over the last decades, but declined when the COVID-19 pandemic struck. In 2021, India was Canada's 13th largest source of imports, while Canada was India’s 30th largest. The current trade relationship is still below its full potential. A gravity model analysis[1] by Ciuriak Consulting reveals that Canada’s merchandise exports to India could have been 242 per cent higher than they were on average between 2017-2019 if Canada had traded at the same level it did with other trade partners. More specifically, the study shows that agri-food products and manufacturing goods were under-traded by 56 per cent and 57 per cent, respectively. A CEPA with India would help address this situation and could help Canada leverage the full potential of bilateral trade with the Asian giant.

It is estimated that a CEPA between Canada and India would boost bilateral trade by C$6-8.8 billion and yield a GDP gain of C$5.1-8 billion for Canada by 2035. Canadian fruits and vegetables, chemicals, wood products, and mineral sectors would also experience substantial export gains from this FTA. As Canada’s largest trading partner, the U.S., is becoming more protectionist, and its second-largest trading partner, China, is becoming less predictable and facing economic woes, Canada must effectively diversify its trade. Given the potential gains from trade that would result from an FTA between Canada and India, India could play a central role in Canada’s trade diversification strategy.

India, currently the fifth-largest economy in the world, has the potential to become the third-largest economy by 2030. India’s growth is propelled by an expanding middle class, increased consumer spending, and rising investments in digitalization and infrastructure. Home to the largest working-age population in the world, India provides a relatively cheap supply of labour. India’s key geopolitical position also makes it extremely important for Canadian interests in the Indo-Pacific region. Developed economies, including Australia, the U.S., the United Kingdom, and the European Union, are already moving fast to strike deals with India. It is now time for Canada to conclude a fully-fledged CEPA with India to leverage the untapped trade opportunities and establish a strong foothold in one of the most strategically important regions in the world.

India’s New Approach to Trade: Collaboration over Competition

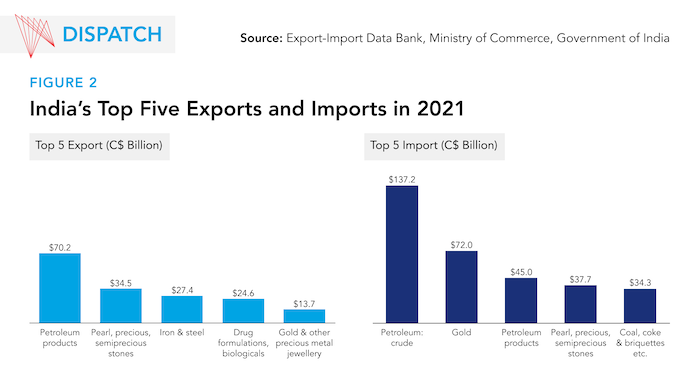

In 2021, India’s merchandise exports and imports reached C$510 billion and C$739 billion, respectively, with the majority of exports going to the U.S. and the majority of imports coming from China. India’s top five imports and exports are in primary industries, except for the exports of drug formulations and biologicals (Figure 2).

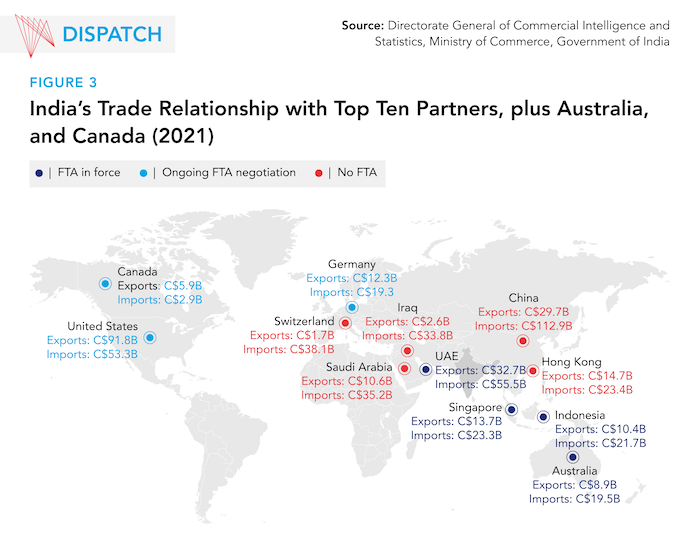

In 2021, the U.S. was India’s top trading partner, followed by China, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia (Figure 3). India currently has fully-fledged FTAs with only three of its top 10 trading partners – the UAE and Singapore and Indonesia through the ASEAN-India CEPA. The lack of FTAs between India and its other top trade partners reflects its past protectionist views toward trade.[2]

India's existing foreign trade policy (FTP) 2015-2020, designed to promote domestic exports while keeping imports in check, was protectionist. India’s withdrawal from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in 2019 is another case in point; fearing that imports would surpass export gains, India decided to withdraw from RCEP negotiations. However, after decades of protectionist trade policies, India seems to be turning toward trade liberalization. In 2022, India began to negotiate and sign FTAs at a rapid pace. The fast-tracked negotiations with the UAE, followed by Australia, the U.K., and the E.U., indicate India’s intention to forge closer economic ties with developed markets.

At the onset of the pandemic, amid slowing exports, the Government of India set an export expansion target of C$1.3 trillion by 2026 from C$369 billion in 2020, hoping to make India a global manufacturing hub. As India realizes it cannot become an export powerhouse without opening up its market, it has started proactively seeking access to resource-rich economies that can supply high-quality raw materials crucial for the Indian manufacturing sector. Experts assume that the next policy, FTP 2023, will capture India’s target to establish a balanced FTA position with complementary economies and focus on collaboration rather than competition.

India is Ready: New Wave of Trade Agreements Signals Change

The India-UAE CEPA and Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA) are the first in a series of FTAs India pursued to meet the export targets it has set for itself for 2026 and ensure its supply of essential raw materials.

Coming into effect on May 1, 2022, the India-UAE CEPA is expected to increase bilateral merchandise trade to C$128.3 billion by 2026 from 2021 levels of C$88.2 billion. Under this agreement, the UAE eliminated import duties on 80 per cent of its tariff lines, accounting for 90 per cent of India’s exports to the UAE, including textiles and apparel, gems and jewelry, pharmaceuticals, and agricultural products. In return, India removed tariffs for 64.6 per cent of the UAE’s exports to India, including petroleum products, crude oil, and iron and steel, among others.

This agreement, concluded within just 90 days of negotiation, signals India’s willingness to fast-track the negotiation process regardless of diverging interests in certain sectors. It also embodies India’s agenda to open new markets and secure access to raw materials and intermediate goods necessary for manufacturing. The agreement contains a chapter on micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), indicating India’s willingness to promote MSME participation in international trade, a key agenda item in Canada’s inclusive trade framework.

The Australia-India ECTA, signed in April 2022, is yet to be ratified by Australia. Once implemented, the agreement is anticipated to double (C$56.8 billion) bilateral trade by 2026 from the 2021 levels of C$28.4 billion. India expects to get a cheaper supply of raw materials, including coal, metallic ores, and critical minerals, which will be crucial for the growth of Indian export-oriented manufacturing industries. Under this agreement, Australia has promised duty-free access to 96.4 per cent of Indian exports to Australia, including textiles, footwear, and pharmaceuticals. In return, India will remove duties for 85 per cent of tariff lines on Australian exports. This ECTA, the first trade deal signed by India with a developed country, confirms India’s readiness to build long-term economic partnerships with complementary markets.

Conclusion

Over the years, Canada has captured only a relatively small slice of India’s rapidly growing market. Historically, India protected its domestic sectors and refrained from forging FTAs with developed countries. But despite challenges in earlier stages of free trade negotiations between Canada and India, there is now momentum not only for an Early Progress Trade Agreement but for a full-fledged FTA between the two nations. The former wants to capture a greater market share in India, and the latter wants to build a long-term economic partnership with a developed economy. With Ottawa and New Delhi set to start the fifth round of negotiations on November 14 in Ottawa, both parties will need to focus on the mutual benefits of trade while resolving diverging issues, such as the completion of the Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (FIPA). If the two parties find mutual ground during the fifth round, they will be on track to finish an EPTA by the end of this year, and, hopefully, reach a CEPA by 2023. If successfully negotiated, the Canada-India CEPA will not only create access for Canadian businesses to one of the fastest-growing economies in the world but also help Canada build a strong foothold in the Indo-Pacific.

[1] The gravity model of trade says that countries tend to trade more with economies that are larger, geographically closer, and enjoy greater economic freedom, as these features reduce the costs of trade. The model estimates the level of trade that should occur based on the geographical distance, economic size, and other parameters and compares it with the actual trade values. (Source)

[2] India benefits from generalized systems of preferential schemes (GSPs) in Switzerland, Germany, and Australia.