This Dispatch is the third in a five-part series by our South Korea Election Watch, a team of young analysts tracking key developments and issues in South Korea’s March 9 presidential election. The series spotlights a segment of the population that most observers believe will play a decisive role in the outcome of the election: voters in their twenties and thirties. It looks at how they view their options in terms of the candidates and main political parties; how they might be impacted by the next administration’s economic policies; how the candidates are trying (or not) to appeal simultaneously to both young feminists and ‘anti-feminists’; their generation’s diverging views on inter-Korean relations; and how the ‘China factor’ has become more complex for them than for their parents and grandparents.

Five years ago, South Korean President Moon Jae-in, then a candidate for the office, pledged to become a “feminist president,” vowing that safety and equality for women would improve under his tenure.

How times have changed.

In the weeks and months leading up to the March 9 election to choose Moon’s successor, both leading candidates have been scrutinized for their comments about feminism. Yoon Seok-youl of the conservative People Power Party (PPP) has linked feminism to South Korea’s stubbornly low birthrate, which hit a record low last year. He even said that feminism prevents healthy relationships between men and women.

His main opponent, Lee Jae-myung of the left-leaning Democratic Party of Korea (DPK), the same party as Moon, has also expressed his “distaste” for feminism. In November, he shared a letter posted online that said that the “madness” of feminism had to be stopped. While Lee was not the letter's author, sharing its content perhaps suggests tacit agreement with at least some of its sentiment.

Making such bold statements may seem rash, as it risks alienating young women who are expected to play a key part in swinging the outcome of the upcoming election. However, the statements from Yoon and Lee may seem less rash considering who they are pandering to: young men who have expressed anti-feminist sentiments.

How did South Korea get from inaugurating a “feminist president” five years ago to two top candidates appealing to the anti-feminist vote? And does the current campaign rhetoric reflect trends in Korean public opinion?

Gender ministry becomes political target

Much of the feminism-related political debate in the current presidential campaign has focused on the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (MOGEF). MOGEF’s creation in 2001, originally called the Ministry of Gender Equality, was seen as a milestone for modern feminism in Korea, a movement that can be traced back to the 1980s. One of its major achievements was eradicating the patriarchal family registry system in which all family members had to be registered under a male family head. Under Moon’s presidency, notable initiatives have included startup loans for female entrepreneurs, incentives to businesses to promote gender balance on their boards, and a pledge to allocate 30 per cent of cabinet posts to women.

Now, however, both Yoon and Lee have indicated that the ministry, in its current form, could be on the chopping block, with Yoon saying it should be abolished and Lee, while somewhat more moderate, saying it needs to undergo several changes. While these are not exactly anti-feminist statements, both are proposing, in effect, a dilution of the government’s commitment to and focus on women’s issues.

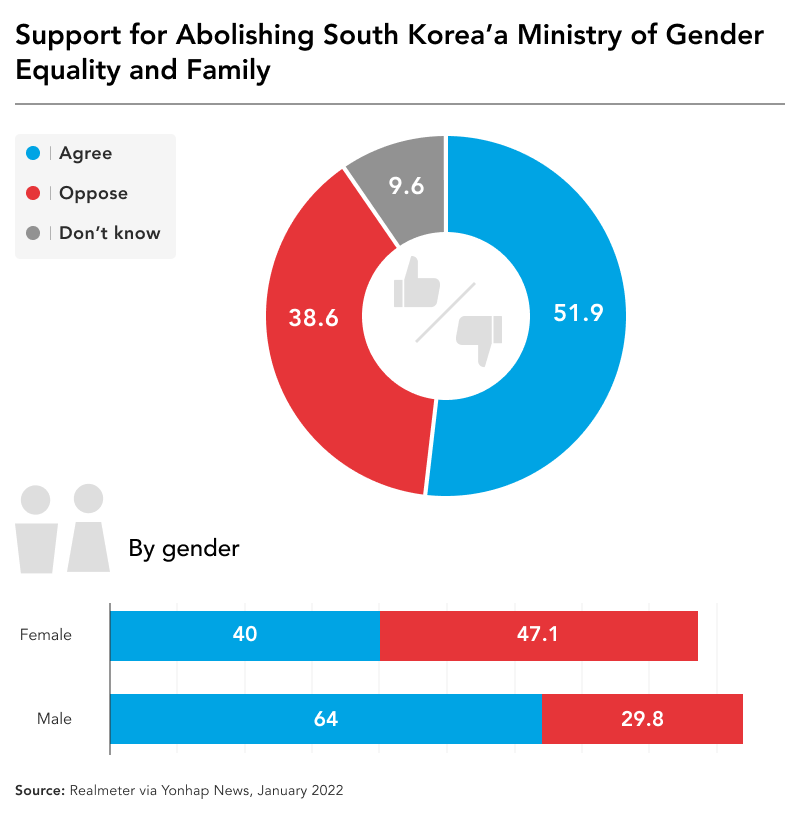

It is likely that such comments are made at least in part with an eye on public opinion. A survey conducted in January showed that 52 per cent of Koreans said they would support abolishing the ministry, with 39 per cent opposed. By gender, the division was starker: 64 per cent of men support the ministry’s abolishment, with 30 per cent opposed; among women, 40 per cent support its abolishment, while 47 per cent were opposed.

While the ministry has previously faced calls for its abolishment, the current anti-feminism sentiment evident in mainstream Korean politics seems to encompass much more than attitudes toward a specific government ministry. Rather, it likely reflects public reactions – and counter-reactions – to several high-profile scandals that have fired up both feminists and anti-feminists in recent years.

Exposing violence and harassment against women

Feminism in South Korea has been experiencing something of a reboot since 2015. One of the core characteristics of this reboot is a focus on violence against women in digital environments. There have been myriad cases revealing how dire this issue is. One recent example is the spycam epidemic in which women were filmed without their consent in private and public spaces, a scandal that landed one K-pop star in prison. Another is the Nth room case from 2020, which revealed that women and underage girls had been blackmailed into sending sexually exploitative images and videos of themselves, which were then distributed to paying customers via an encrypted messaging app called Telegram.

Korea’s #MeToo Movement has ensnared not only the country’s entertainment industry, but also members of its political sphere. Disgraced politicians include Ahn Hee-jung, governor of South Chungcheong Province; Oh Keo-don, former mayor of Busan, Korea’s second-largest city; and, Park Won-soon, the former mayor of Seoul, who committed suicide in 2020 shortly after being accused of sexual harassment.

The seriousness and prevalence of these incidents have certainly shaped a variety of views in South Korea that could be labelled ‘feminist.’ They have also fuelled an anti-feminist backlash, especially from young men. Part of the intensity of the backlash is attributed to feminism’s reputation in Korea. For example, online communities such as Megalia used a mirroring method – that is, mimicking the comments found in men-centred online communities – to expose the misogyny they face. Megalia and its offshoot online communities like WOMAD have even linked feminism to misandry, defined as a hatred of men.

The conflation of all types of feminism with its more radical and anti-male expressions is perhaps why there has been such a harsh, sometimes deadly, reaction against any potential ties to feminism in South Korea’s mass media. Last summer, 20-year-old Olympian An San won three gold medals as an archer. Her newfound national fame was overshadowed by harassment as her short hair and enrollment at a women’s university were taken as symbols of her feminist status. Similarly, the founder and CEO of GS25, a convenience store chain, stepped down after the brand had to alter, then eventually retract, printed ads because they were linked to a supposed feminist symbol, namely, a hand gesture where the index finger and thumb are almost touching, an assumed mockery of a particular male body part. The gesture had been adopted by Megalia, and critics accused GS25 as well as other companies of supporting feminism and misandry.

Even the most well-intentioned initiatives can catch flak from anti-feminists; a suicide prevention website set up during the pandemic for young women had to temporarily go offline because of cyberattacks from those who accused it of disregarding men’s lives.

What’s up with young Korean men?

Of clear interest to Korea’s presidential candidates is that the most fervent supporters of anti-feminism seem to be men in their twenties. An online survey conducted by Munhwa Ilbo reported that two-thirds of men in their twenties, as well as 63 per cent of men in their thirties, equated feminism with an assertion of women’s superiority. The same survey reported that women in their twenties had a much different view: 61 per cent thought of feminism as gender equality.

What unites the two genders, however, is that they both feel a sense of victimhood. Specifically, while women turn to feminism to protest the discrimination and sexual violence they face, men shun it because they believe it has victimized them in modern Korean society. The misogyny prevalent among men in their twenties is closely tied to the ideals of meritocracy so heavily ingrained in their experiences. As youths in the South Korean education system, where ranking is largely determined by exams, boys grow up seeing girls excel in the classroom. As young men facing competitive job and housing markets, they note that conscription and mandatory military service are only for men. Meanwhile, they perceive feminism and feminist politicians as ushering in an era of structural discrimination against men.

However, many young men have not witnessed the reality that women face in South Korea. Instead, those who have not yet joined the labour market see the MOGEF and Moon’s policies targeted at breaking the glass ceiling as reverse discrimination in a post-feminist society. But on the contrary, discrimination against women remains alive and well. South Korea has the worst gender pay gap of all OECD countries surveyed, and according to the 2021 Global Gender Gap Report released by the World Economic Forum, Korea sits at 123 out of 156 countries for economic participation and opportunity for women.

But statistics aside, young men seem to feel that they are now the victims, as they have been asked to “compensate for the sexist privileges” that older Korean men got to enjoy. In their view, the benefits that older South Korean men enjoyed as “patriarchs who oversee women” are long-gone, and in their place are affirmative action policies and a feminist culture that penalizes men on the basis of their gender.

Preview in politics

Yoon and Lee, the two men vying for the South Korean presidency, have had a preview of how the anti-feminism factor can influence election outcomes. In the Seoul and Busan mayoral by-elections held last year after the incumbent DPK mayors were disgraced, the PPP candidates won in the two cities – Korea’s largest. Oh Se-hoon, a conservative who was elected mayor of Seoul, received support from 73 per cent of male voters in their twenties, according to an exit poll conducted by three major broadcasting stations.

To capitalize on this sentiment, both Yoon Seok-youl and Lee Jae-myung have made statements and taken actions to rally support from anti-feminist young men. For example, Lee cancelled interviews with two media outlets after male supporters claimed they were “too feminist.” Yoon pledged to contribute to the online gaming industry, where feminism has been called an “antisocial ideology,” and made an appearance at the 2022 League of Legends Champions Korea Spring.

It should be noted that not all South Korean men in their twenties are anti-feminist. As such, both Yoon and Lee have also had to show that they are not completely shunning feminists. Yoon recruited two feminist figures, Lee Soo-jung, a professor of forensic psychology at Kyonggi University, and Shin Ji-ye, the former head of the non-profit Korean Women’s Political Network, into his election committee. Their appointments were not without controversy. Lee Soo-jung eventually stepped down from her advisory role on Yoon’s camp, citing disagreements with the candidate’s position on gender issues. The resignation came shortly after comments made by Yoon’s wife suggesting that sexual scandals occurred because DPK politicians did not pay off their victims were made public.

Lee has also tried to ensure that his campaign is not seen as excluding women. He recruited Park Ji-hyun as the Chairperson of the Special Committee on the Elimination of Digital Sex Offenses. She is an activist in her twenties who took part in exposing the Nth room case. He has also made appearances on YouTube channels that deal with women’s issues and feminism and held a policy conference with CEOs of startups dedicated to helping working mothers.

These gestures notwithstanding, the current presidential election is a stark contrast to the previous one, when Moon embraced the role of becoming “a feminist president.” Now, even his successor, Lee, is taking steps to distance himself from that label.

Campaign season is often a time when rhetoric gets heated and overblown. And there are no guarantees that what politicians say in the lead-up to the election will inform their policies once they become president. But their willingness to play to certain attitudes suggests South Korea is in for a longer-term pattern of anti-feminism in Korean politics.

About the South Korea Election Watch (SKEW):

The SKEW is part of APF Canada’s election watch series, first launched in 2016, of graduate and undergraduate students and young professionals working with APF Canada to monitor and analyze key national-level elections in the Asia Pacific, including their implications and the underlying social, economic, and political issues.

Other Dispatches in this Election Watch Series:

Will the Honeymoon Period for South Korea’s President-Elect Be Cut Short? – Daniel Jacinto and Chloe Kang

Places, Parties, and Politicians: A Primer on South Korea’s 2022 Presidential Election – Daniel Jacinto

South Korea’s Presidential Candidates Seek Solutions to Persistent Economic Problems – Kevin Seo

South Korea’s Presidential Contenders Court Young, Male Anti-Feminists – Lynn Lee

South Korea’s Presidential Candidates Formulate North Korea Policies Amid Shifting Public Opinion – Chloe Kang

The ‘China Factor’ Looms Large Over South Korean Presidential Candidates’ Foreign Policy Choices – Lina Park