This Dispatch is the second in a five-part series by our South Korea Election Watch, a team of young analysts tracking key developments and issues in South Korea’s March 9 presidential election. The series spotlights a segment of the population that most observers believe will play a decisive role in the outcome of the election: voters in their twenties and thirties. It looks at how they view their options in terms of the candidates and main political parties; how they might be impacted by the next administration’s economic policies; how the candidates are trying (or not) to appeal simultaneously to both young feminists and ‘anti-feminists’; their generation’s diverging views on inter-Korean relations; and how the ‘China factor’ has become more complex for them than for their parents and grandparents.

In last year’s hit South Korean television series Squid Game, a group of downtrodden and indebted contestants participate in a series of violent children’s games for the chance of winning a large cash prize. While the show was praised for its esthetic set designs and creative story writing, it also offered a glimpse into the deep economic fractures at the heart of Korean society. From rampant indebtedness to unaffordable housing prices, Squid Game shed light on the socio-economic realities that sharply divide and stratify the world’s 10th-largest economy.

On March 9, as South Koreans head to the ballot box to elect their next president, questions surrounding inequality, unemployment, and affordability – and perhaps a new vision for the country’s beleaguered economy – will undoubtedly be front of mind.

Failure to deliver

Recent polls suggest that economic policies will play a significant role in determining who will be the next occupant of the Blue House, the South Korean president’s official residence. In a recent survey of residents of the capital city of Seoul, 19 per cent stated that their number one issue in the upcoming year was the cost of living. The next two issues were youth unemployment and job creation, followed by mortgages and consumer debt. Another recent poll found that material and economic well-being were the most important sources of meaning for people in South Korea.

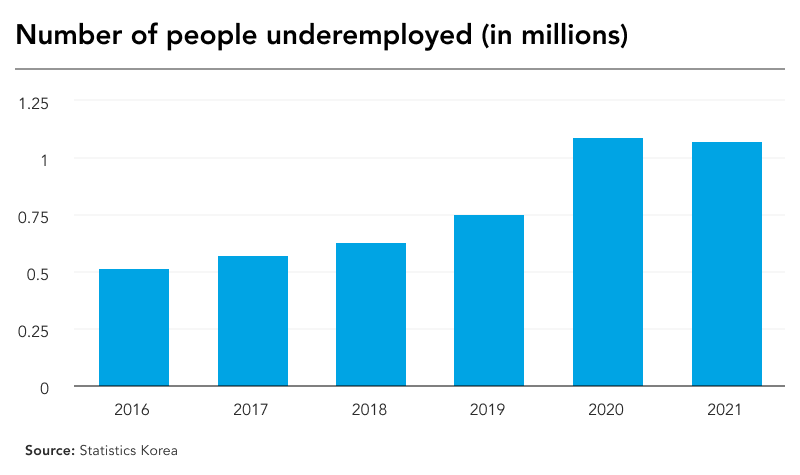

Many of these issues were evident at the start of incumbent president Moon Jae-in’s tenure in 2017. Moon ran on an economic platform that promised to lower youth unemployment rates, encourage affordable housing, and narrow the wealth gap. Despite his administration’s best efforts, the de facto jobless rate, which includes the unemployed and underemployed among the economically active population, has jumped from 22.9 per cent to 27.2 per cent for South Koreans aged 15 to 29. The average apartment price in Seoul has increased a staggering 90 per cent under Moon’s tenure. Meanwhile, wages over the same period have only increased 20 per cent, giving little indication that wealth inequality has been meaningfully addressed.

South Korea’s pandemic economy

In South Korea, as is the case elsewhere, the pandemic seems to have widened the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots.’ During the first year of COVID-19, Korean conglomerates such as Samsung and LG boasted record-breaking profits, while workers and small businesses floundered under the weight of COVID-19 restrictions. As South Korea braces for a new wave of infections, indicators suggest that the country’s economy is in dire straits. In January, South Korea experienced a 3.6 per cent year-over-year increase in inflation, the fastest pace in almost 10 years. Due to this upward inflationary pressure, the debt-to-GDP was expected to reach nearly 21 per cent by the end of 2021 and up to 36 per cent by the year 2026.

The numbers further suggest that South Korea’s economic woes disproportionately affect the financially vulnerable. During the second quarter of 2020, disposable income for the top 20 per cent of South Koreans was 5.59 times greater than that of the bottom 20 per cent, while a year earlier, this number was only 5.03 per cent.

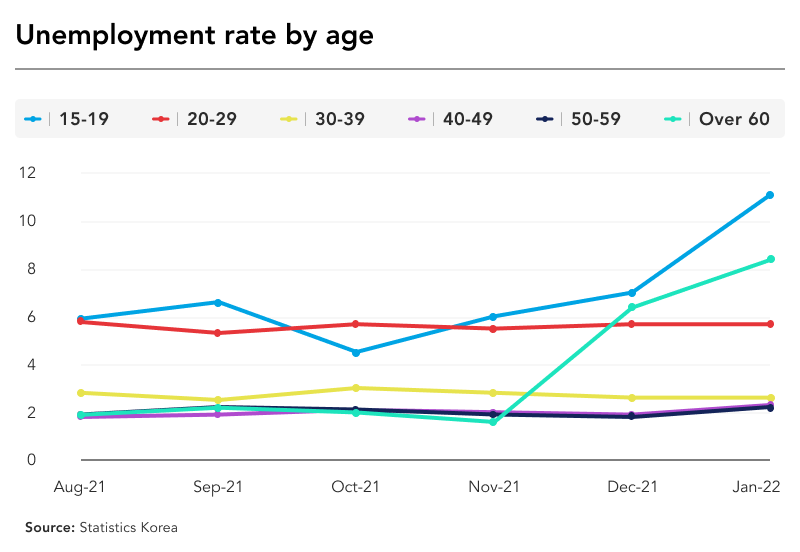

The demographic most impacted by economic inequality is Korean youth. In June, the number of discouraged workers – those willing and able to work, but have given up seeking employment after a prolonged period of unemployment – increased to 583,000, 46,000 more than the year before. Of this number, workers between the ages of 20 and 30 accounted for almost half of the total, an 8.2 per cent increase from the previous year. In July, less than 59 per cent of people in their twenties were employed, compared to three-quarters of people in their thirties and nearly 78 per cent in their forties. For comparison purposes, of the 33 OECD countries, South Korea ranks 27th in the employment rate for people aged between 25 and 54.

The low rates of employment for young professionals are doubly concerning when considering the proportion of South Korea’s aging population. According to the most recent figures, nearly 17 per cent of the Korean population is aged 65 or older, which the UN considers an “aged society.” By 2025, South Korea is projected to become a “super-aged society” (meaning 20% of the population is 65 or older). The relative poverty rate for this demographic is reported to be a shocking 43 per cent, the highest elder poverty rate among OECD countries. Given South Koreans’ long life expectancy, these figures suggest a greater strain on the country’s health-care and social security systems in the future, as citizens will have to divert more resources to provide for the elderly. Moreover, due to South Korea’s historically low fertility rates, which dropped to a historic low of 0.84 in 2020, a rapidly decreasing labour force will be forced to support an increasingly large, unproductive, and impoverished proportion of the population.

Candidates float policies with populist appeal

Desperate to provide answers to these profound challenges, this year’s presidential candidates are running on unique economic platforms. Representing the liberal Democratic Party of Korea (DPK), former Gyeongi-do Governor Lee Jae-myung is campaigning on the promise of a Universal Basic Income program. If elected, Lee would provide all eligible Korean citizens with an annual cash subsidy of at least 250,000 won (about C$267) starting in 2023. In addition, every South Korean between the ages of 19 to 29 would receive approximately 1.25 million won (C$1,335). Lee’s longer-term plan is to increase the subsidy to one million won (C$1,068) for every citizen, and two million won (C$2,136) for every person in their twenties. Taking a government-led approach to economic growth, Lee has also pledged to invest in a digital transition and create two million jobs in innovative sectors. Although in Lee’s initial bid for the Blue House he was seen as a somewhat fringe candidate, his defeat of a more mainstream alternative to represent the DPK suggests that at least liberal-leaning Korean voters may be ready to buck the status quo on economic policy.

His conservative rival, Yoon Seok-youl of the People Power Party (PPP), has promised to loosen corporate regulations and cut capital gains taxes to create more business-friendly conditions, which he believes are crucial for kick-starting the Korean economy and creating more jobs. While Yoon is a more traditional neo-liberal than Lee, the former prosecutor has shown his willingness to flirt with populist ideas. In August, Yoon released his plan to provide 2.5 million new homes across the country to combat rising home prices. He also pledged to provide 300,000 affordable small homes for South Koreans in their twenties and thirties in the hopes of attracting the youth vote.

While both candidates have made big promises, some critics have questioned their ability to follow through. Public dissatisfaction with the ruling Democratic Party of Korea is rising, including its inability to tackle rising property prices. But the party is also being tarnished by allegations of official corruption and abuse of power. That includes Lee Jae-myung, who is facing a major real estate scandal in which he is alleged to have given preferential treatment to an asset management company during his time as the mayor of Seongnam city. The questions surrounding Yoon Seok-youl have to do at least partly with ability: he has never served in elected office and has no track record of implementing economic policies.

Tall order for next president

At the conclusion of Squid Game, the game’s unassuming architect says: “Do you know what someone with no money has in common with someone with too much money? Living is no fun for them.”

That observation helps define the mood during this election season. As South Korea slowly emerges from the pandemic, the next government will likely be keen on encouraging investment in technologies and digital infrastructure to cement the country’s position as a competitive economic powerhouse in the region. But without addressing the deep-seated challenges of inequality, debt, and inflation, Squid Game’s message of survival amid economic anxiety will continue to ring true for many ordinary South Koreans.

About the South Korea Election Watch (SKEW):

The SKEW is part of APF Canada’s election watch series, first launched in 2016, of graduate and undergraduate students and young professionals working with APF Canada to monitor and analyze key national-level elections in the Asia Pacific, including their implications and the underlying social, economic, and political issues.

Other Dispatches in this Election Watch Series:

Will the Honeymoon Period for South Korea’s President-Elect Be Cut Short? – Daniel Jacinto and Chloe Kang

Places, Parties, and Politicians: A Primer on South Korea’s 2022 Presidential Election – Daniel Jacinto

South Korea’s Presidential Candidates Seek Solutions to Persistent Economic Problems – Kevin Seo

South Korea’s Presidential Contenders Court Young, Male Anti-Feminists – Lynn Lee

South Korea’s Presidential Candidates Formulate North Korea Policies Amid Shifting Public Opinion – Chloe Kang

The ‘China Factor’ Looms Large Over South Korean Presidential Candidates’ Foreign Policy Choices – Lina Park