The South China Sea is one of the most important waterways in the world. Every year, $5 trillion worth of goods pass through it, including almost all of the oil imported by China, Japan, and South Korea. Tens of millions of people depend upon its fisheries for either food or livelihood. It is the strategic gateway between the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean.

It is also the scene of multiple overlapping maritime and territorial claims that have erupted into violence in the past and threaten to do so again.

At the heart of the South China Sea dispute are legal questions about who is entitled to exercise jurisdiction over land, sea, and air. The territorial sovereignty disputes primarily concern the Spratly and Paracel Islands, though various other “features” are under dispute as well. Territorial rights largely determine both maritime jurisdiction and access to airspace. China, however, partly based its expansive if ambiguous claim to jurisdiction over virtually the entire South China Sea on historical title, as indicated by the so-called nine-dash line (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overlapping claims in the South China Sea

Settling territorial disputes can be quite complicated under international law, as a wide variety of considerations can bear on determining which of two (or more) claimant states has the stronger case for title. These include the preferences of the inhabitants (if any), historical use or possession, current control, treaties or other agreements, and international recognition.

Settling disputes over maritime rights is, in principle, much simpler, as entitlements are specified in great detail in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to which most countries of the world—including all claimant states in the South China Sea—are party, and which is now so widely accepted that even states that have not ratified it, such as the United States of America, treat most of its provisions as settled customary international law.

Rock and role

Under the terms of UNCLOS, states are entitled to exercise full control over a “territorial sea” extending 12 nautical miles from their coasts; enjoy policing rights a further 12 nautical miles in a “contiguous zone” for purposes of customs, immigration, or sanitary law enforcement; and have jurisdiction over fisheries and other natural resources (such as gas and oil deposits) in an “exclusive economic zone” (EEZ) that can extend up to 200 nautical miles. UNCLOS includes various twists and complications for such things as historic bays and continental shelves, but these are not of much concern in the South China Sea.

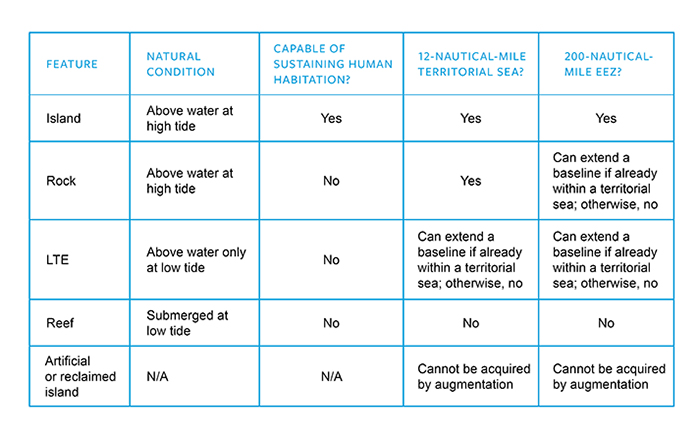

What is very much of concern in the South China Sea is the legal status of the Spratlys, Paracels, and various other rocks, reefs, and shoals. Under UNCLOS, maritime entitlements very much depend upon whether something in its “natural condition” (i.e., neither reclaimed nor artificially augmented) is, legally speaking, an “island” (above water at high tide and capable of sustaining human habitation), a “rock” (above water at high tide but incapable of sustaining human habitation), or a “low-tide elevation” (LTE, submerged at high tide; see Table 1).

Table 1. Legal definitions of features and attendant maritime rights

There are many different legal mechanisms available for settling maritime and territorial disputes, including arbitration, adjudication, and mediation. Indeed, states have used these frequently over the centuries, and almost always with success. But, until recently, no claimant state has managed to get a duly designated legal body to pronounce authoritatively on any of the key issues in dispute in the South China Sea.

That changed on July 12, when a tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration issued its final ruling in Philippines v. China. The Philippines brought the case under compulsory arbitration provisions of UNCLOS, inter alia, to clarify the legal status of various features, to challenge the legality of China’s nine-dash line, and to secure relief from Chinese interference with the activities of Filipinos in their traditional fishing grounds and in the Philippines’ EEZ. China stridently refused to participate in the proceedings, challenging the tribunal’s jurisdiction and insisting that it would only recognize settlements achieved through bilateral negotiations. But, while China refused to participate, the tribunal bent over backwards to take into account Chinese views and positions, and delivered a fair and meticulous decision.

The ruling was a virtual clean sweep for Manila. On no issue did the tribunal come down in favour of China. On only one did it decline to make a ruling: on the standoff at Second Thomas Shoal, where the Chinese Coast Guard actively tries to prevent the resupply of the grounded Philippine military ship, the BRP Sierra Madre.

Two findings stand out. The first is that the nine-dash line has no basis in law. The South China Sea is an international waterway, and littoral states’ maritime jurisdictions are limited entirely to what UNCLOS says about 12-nautical-mile territorial seas, contiguous zones, EEZs, and continental shelf rights.

Second, the tribunal ruled that according to UNCLOS provisions, there are no “islands” in the South China Sea, only “rocks.” This is important because a legal island is entitled to a 200-nautical-mile EEZ in addition to a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea. If the tribunal had declared any of the disputed features in the South China Sea to be islands, this would have raised the stakes of the territorial disputes in the region dramatically. But because the tribunal ruled that there are only rocks (entitled only to a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea) and LTEs or permanently-submerged shoals (which carry no maritime entitlements), littoral countries’ EEZs can only be projected from their metropolitan coastlines. Since the total rock-based 12-nautical-mile territorial seas amount to less than 1.5 percent of the surface area of the South China Sea, the tribunal’s ruling has dramatically reduced the stakes involved in the territorial disputes.

The tribunal did not rule on which country enjoys sovereign jurisdiction over which particular rock; UNCLOS provides no basis for adjudicating territorial disputes, only maritime ones, and the Philippines did not ask the tribunal to do so. Nevertheless, the fact that no country can claim an EEZ extending from any of the disputed features in the South China Sea means that China has no basis for challenging Manila’s EEZ claim, because the two countries’ EEZs do not overlap. It also means that China’s new artificial island at Mischief Reef is right in the heart of the Philippines’ EEZ, and that China has no right to interfere with Philippine boats that wish to fish the rich waters in and around Scarborough Shoal, though China also has the right to fish these waters, based on historical usage.

Beijing’s conundrum

For Beijing, the tribunal’s ruling was a major blow. No country likes to have its official position on a major international issue dismissed as illegal. In addition, the decision put Chinese leaders in a bind. Chinese public opinion had completely internalized the government’s line and reacted in a bellicose nationalist fury. At the same time, China’s rival claimants, and most of the rest of the international community, had clearly signaled in advance that they expected China to abide by the ruling, no matter what it turned out to be (expectations were that Manila would win on many points, including some of the key ones, but no one had any idea just how sweeping Manila’s victory would be). Caught between a rock and a hard place—between a domestic imperative to show firmness and an international imperative to comply—it was not obvious how Chinese leaders would avoid either a crisis of legitimacy at home or a dangerous international escalation in tensions.

Thus far, things have gone much better than anyone might have hoped or expected. Credit goes to both sides. On the Chinese side, Beijing contented itself with reiterating its position that the tribunal lacked legitimacy and that the ruling was null and void. It did not take concrete action to demonstrate its displeasure. Among the things China might have done to gratify domestic opinion that would have made an already delicate international situation much worse were the following:

(1) accelerating its island-building program;

(2) overtly militarizing its existing artificial islands;

(3) declaring an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the South China Sea, much as it did over the East China Sea in 2013; and/or

(4) withdrawing from UNCLOS.

Any of the first three would have been seen as a provocative challenge, most likely prompting countermeasures in the form of increased freedom of navigation operations by the U.S. Navy, fresh regional deployments by U.S. forces, and the announcement of rival—and overlapping—ADIZs by Vietnam, the Philippines, and/or Malaysia. These would have heightened risks of military conflict, deliberate or otherwise. Withdrawing from UNCLOS would not, by itself, raise the dangers of military conflict, but it would represent a major blow to the rule of law and cast doubt on a rising China’s commitment to a rule-based global order. Circumstantial indications are that China was prepared to take one or more of these dangerous steps, but that cooler heads prevailed.

On the opposite side of the issue, the rest of the international community did an excellent job of resisting the temptation to triumph at China’s expense. Official statements were mild; public demonstrations were muted; no one issued demands that China immediately and visibly comply with the ruling. The Philippines’ new president, Rodrigo Duterte, did a particularly good job of smoothing the waters with China, with new offers of co-operation and harsh statements about the United States and its president, Barack Obama. No doubt, from Beijing’s perspective, the opportunity to distance Manila from its primary military ally represented an unforeseen geopolitical silver lining to an otherwise very dark cloud. A tangible indication of the sudden, surprising improvement in Sino-Philippine relations is the fact that the Chinese Coast Guard has withdrawn from Scarborough Shoal and Philippine fishers once again enjoy unfettered access.

Long-term Implications

How will the tribunal’s ruling affect security governance in the region as time goes by? There are essentially three ways things could play out:

- Stalemate: In this scenario, China would stick to its line that the ruling is null and void, and continue to behave in accordance with its official claims while studiously avoiding provocative measures of its own, such as building new artificial islands, permanently stationing military forces on existing ones, declaring an ADIZ, or withdrawing from UNCLOS.

The most likely outcome of this scenario would be that at some point China would undertake an enforcement measure that Beijing and the Chinese people believe to be legitimate—continuing unilateral fisheries enforcement, for example—triggering an amplified reaction by others motivated and supported by the tribunal’s ruling. This means that the stalemate scenario is almost certainly unstable: the waters may be calm at the moment, but storm clouds are clearly on the horizon. In the meantime, inaction on the tribunal’s ruling will paralyze confidence-building, trust-building, and institution-building. This scenario, in short, would represent a dangerous missed opportunity.

- Deferred defiance: In this scenario, at some point Beijing throws caution to the wind and takes matters into its own hands in defence of its sense of entitlement. Conceivably, this could occur because some domestic issue in China arises to threaten the regime’s legitimacy, prompting Chinese leaders to use external conflict for the purpose of domestic diversion, or because hard-liners who have thus far lost the debate to advocates of a muted response eventually gain the upper hand in the Byzantine bureaucratic battles typical in Beijing.

While there is, in fact, relatively little historical evidence to suggest that regimes that feel threatened domestically deliberately risk international conflict to shore up their position, we know that hawks and doves tussle over Chinese policy frequently. Indeed, it would appear that this is precisely what underpins China’s unnecessarily provocative-looking declaration of an East China Sea ADIZ. If China’s foreign policy hawks are able to argue that a muted response is not paying dividends, they can be expected to advocate bolder action in support of “core” national interests.

- Gradual accommodation: In this scenario, China’s neighbours engage it constructively on functional issues as a way of demonstrating the practical benefits of being seen as a team player, giving Beijing both the face and the time to let go of its outright rejection. For a while—perhaps for a very long while—letting go of outright rejection might simply take the form of toning down and eventually silencing state rhetoric repudiating the tribunal’s ruling.

Eventually, China might go the extra yard, declaring that it will abide by the ruling for the sake of regional peace and co-operation. In the best of all possible worlds, such a declaration would include language to the effect that the tribunal was legitimate and its ruling sound after all. This seems rather too much to hope at the moment, but in any case it is almost certainly unnecessary. The customary practices of states are themselves authoritative under international law, and action in accordance with the ruling would eventually constitute acknowledgement of its legitimacy with or without an explicit statement to that effect.

The third scenario is, of course, preferable to either of the first two. It effectively takes advantage of the tribunal ruling to promote co-operation, cultivate empathy, build trust, thicken and deepen regional norms, and allow the institutions and practices of Asia-Pacific security governance to evolve and mature. This is in the interest not only of the Philippines, other rival claimants, and the United States, but also, I would argue, of China. In the long run, everyone benefits from legal clarity, from convergence on the rules of the road, and from the opportunities to co-operate that follow.

Opportunities for Canada

What role, if any, can Canada play in supporting gradual accommodation?

The most immediate and arguably most important issue crying out for co-operation is fisheries management. Fish stocks are already under stress in the South China Sea, and unregulated fishing threatens their collapse. There is an urgent and compelling need for conservation, environmental protection, and sustainable fisheries management. To this point, China has been attempting to provide these, but it has been doing so unilaterally, and, it would appear, discriminatorily. Since fish know no boundaries, only a co-ordinated, multilateral system of management can assure the long-term viability of stocks and satisfy the perceived demands of distributional justice. Canada has a great deal of knowledge and experience with fisheries management. While not all of Canada’s experience has been positive—the collapse of the North Atlantic cod fishery is but the most obvious and most costly case—even failure can be instructive. Canada has learned a great deal that is of value, and has both the technical and the organizational capacity to pass it on.

Canada has a great deal to contribute to several other functional issues also. As the host country for the International Civil Aviation Organization, Canada has broad and deep expertise in aviation safety. Canada is also generally acknowledged to punch above its weight in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, and as the country with the world’s longest coastline and largest number of internal lakes and rivers, it has considerable expertise in maritime safety and in search and rescue. Canada can promote co-operation by offering services and advice on these issues as well.

At the end of the day, Canada’s stake in the South China Sea is indirect. It is not a claimant, and is geographically far removed from the scene. But as an advanced economy with a diverse multicultural, diasporic population, it is highly invested in, as well as exposed to, globalization. Thus a peaceful, orderly, rule-governed international order is very much a Canadian national interest. Canada would stand to lose a great deal if conflict in the area disrupted the global economy, threatened humanitarian catastrophe, undermined international law, or brought powerful countries such as the United States and China to the brink of military conflict. Accordingly, Canada has every reason to hope that the Philippines arbitration tribunal ruling will come to serve as the basis for a long-term improvement in regional security governance, and every incentive to do what it can to encourage trends in that direction.