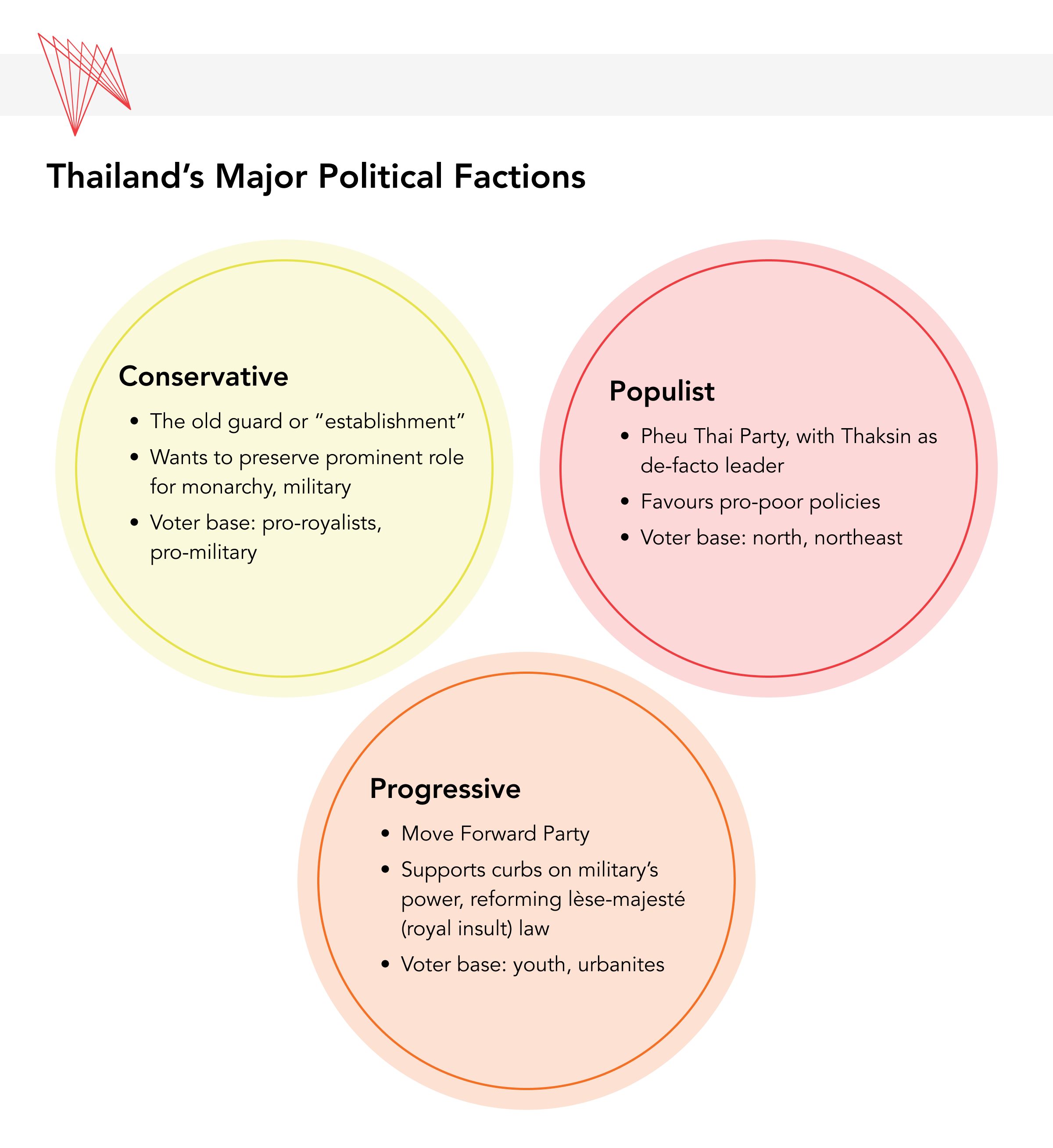

Over the past year, Thailand’s tumultuous politics have frequently made international headlines. This was most notable when the progressive Move Forward Party, broadly aligned with the 2020-2021 pro-democracy and monarchy-reform protests, won the May 2023 elections only to be denied power by the military-appointed upper house three months later.

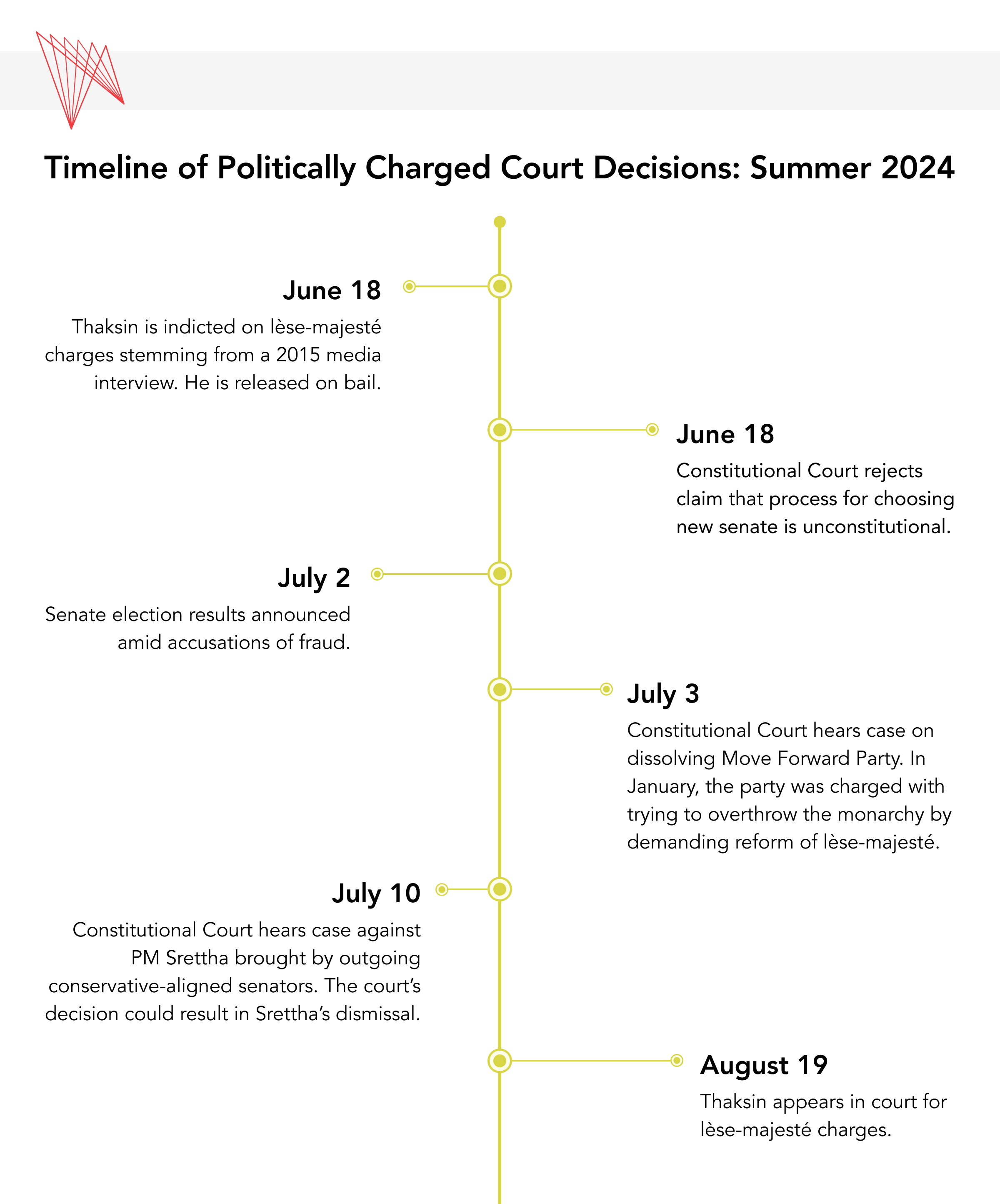

The lack of substantive democracy in Thailand was thrust back into the spotlight in April 2024, when the constitutional court accepted a petition to disband the Move Forward Party and suspend its leaders for their proposal to amend the country’s royal defamation law. On May 14, Thailand came under international criticism after the death of Netiporn “Bung” Sanesangkhom, who had been on a hunger strike to protest the pre-trial detention of the many activists who had participated in the 2020-2021 protests.

Simultaneously, in late May, Thailand watchers got another reminder of the potential volatility in Thai politics when its attorney general’s office announced that former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, recently rehabilitated after 15 years in exile, would face trial for allegedly insulting the monarchy in an interview he gave with a South Korean newspaper in 2015. This news came days after it was announced that the current prime minister, the Thaksin-affiliated Srettha Thavisin, may be forced out of office by the constitutional court for appointing a convicted criminal to cabinet. Many analysts have interpreted these recent developments as signs that the “grand reconciliation” and governing coalition between military-aligned parties and Thaksin’s Pheu Thai party has come under serious strain.

On June 17, Thaksin was officially indicted and now awaits trial, while the constitutional court announced that it would continue its proceedings on the Move Forward Party and Srettha cases in July. With Thailand now facing the real possibility of descending once again into political instability and another democratic crisis, Canada should remain committed to its foreign policy principles of encouraging and defending human rights and democracy, as stated in its Indo-Pacific Strategy and elsewhere. It should do so, first and foremost, because the last three decades of Thai political history have demonstrated that democracy and human rights are also Thai values.

Three decades of democratic struggle

The antecedents of Thailand’s current political crisis are more than three decades in the making. In 1992, popular protests against military rule and its intervention in politics forced the armed forces back into their barracks. From that point until 2001, Thailand had an imperfect but nevertheless substantial period of democratic rule, which included an elected upper house of parliament, the creation of independent institutions to check the power of the prime minister and cabinet, and a flourishing of non-governmental organizations and other civil society groups. The 1997 “People’s Constitution,” the culmination of this period, is considered the most democratic constitution in Thai history.

However, it was also common during this period for elected politicians to engage in clientelist practices through which they gained votes in their constituencies in exchange for money and favours rather than by enacting transformative national programs and policies. This tendency worked against the formation of large national parties and, instead, favoured multi-party coalitions of smaller parties that were relatively weak and unthreatening to long-standing unelected elements within the Thai state: the bureaucracy, the military, the monarchy, and affiliated business conglomerates.

The election in 2001 of billionaire telecommunications tycoon Thaksin Shinawatra and his Thai Rak Thai party eliminated many of the political system’s imperfections. For example, Thaksin’s government developed national programs such as the 30-baht health scheme and multiple village-improvement initiatives, thereby winning the loyalty of voters in the economically underdeveloped and populous north and northeast and transforming Thai Rak Thai (which later became the People’s Power Party and then the Pheu Thai Party) into an electoral juggernaut. Large segments of the Thai population had become empowered through the vote for the first time, making Thai democracy more meaningful.

However, Thaksin’s government also introduced new problems into the Thai political system. His majoritarianism and colonization of the institutions – that is, his insertion of his own people into these institutions – were meant to check the political executive but led to abuses of power and corruption. This style of governance made Thaksin the enemy of many Thais, particularly the Bangkok middle class, which understood that the rule of law and moral leadership – not just majority rule – were fundamental to democracy.

Ultimately, however, Thaksin’s challenges to the aforementioned traditional elite were what resulted in his ouster in a military coup in 2006: he circumvented the bureaucracy in policy formation and delivery, tried to promote loyalists within the military, did favours for his business cronies, and was accused of acting too presidential within a parliamentary system in which the king has been historically highly revered. Yet, despite authoritarian manoeuvres on both sides of the political divide during this period, the pro-Thaksin (“red shirt”) vs. anti-Thaksin (“yellow shirt”) street politics that generated much political turbulence in this decade (including another military coup in 2014), should be partially understood not as a battle between democracy and authoritarianism, but as a battle between two different conceptions of democracy, albeit a battle co-opted by elites. While some red shirts were more loyal to Thaksin than they were to democratic norms, and many yellow shirts espoused undemocratic solutions to Thaksin’s majoritarianism, many Thais on both sides of the divide were simply pushing for their voices to be heard and for the power of the elites to be checked. Recognizing the democratic demands in both red and yellow camps, the Future Forward Party, the disbanded predecessor to Move Forward, strategically chose the colour orange.

The ongoing push for democracy and human rights since the 2014 coup is more evidence that a substantial percentage of Thais value these principles. Future Forward received broad support in 2019, as did the youth-led protests in support of Future Forward in 2020-2021 and Move Forward in the 2023 election. All of these movements put forward proposals to deepen popular control and accountability in Thailand’s politics, including removing the military’s influence over political institutions and the economy as well as redrafting the constitution to bolster provisions related to civil and political rights. The protesters and Move Forward went as far as suggesting curbs on the power of Thailand’s ultimate unelected institution: the monarchy.

The 2023 election, in which the military-aligned parties were routed by Move Forward and Pheu Thai, was a clear rebuke of the country’s anti-democratic forces and their way of governing. The younger generation of Thais, fuelled by exasperation with elite conflict and military rule, mobilized through social media, and echoing demands for deeper democracy and justice across the globe, have been the major force driving this dramatic political shift. While deep red supporters of Thaksin and deep yellow supporters of ultra-royalism remain, the divisions of “old Thailand” seem to be gradually giving way to the pro-democratic voices of “new Thailand.” As these young Thais are the future of the country’s politics, a Canadian foreign policy that is more respectful and reflective of their wishes would be beneficial for Canada-Thailand relations in the long term.

Canada's opportunity to support Thai democracy

There are few countries in Southeast Asia where the demand for democracy has been as constant and as mass-based as it has been in Thailand. Indeed, decades of struggle indicate that the majority of Thais genuinely value democracy. Nevertheless, a full-fledged democratic system and a commitment to human rights remain elusive in Thailand due to the continued assault on the popular will by traditional power holders.

That tension possibly puts Canada in an awkward position. Canada has been inconsistent in how it has expressed support for human rights defenders and inclusive democratic governance. On one hand, it has been vocal in criticizing violations in Hong Kong, Myanmar, and other countries beyond the Indo-Pacific. On the other hand, since the 2014 coup, the Canadian government has refrained from publicly commenting on some noteworthy violations of political rights and democratic norms within Thailand. These include:

- the less-than-democratic referendum on the 2017 constitution, which led to a military-appointed upper house and de facto military appointment of the prime minister;

- harsh repression during the 2020-2021 pro-democracy protests;

- the pre-trial detention and jailing of political activists using lawfare, most notably under the lese majeste, sedition, and the computer crimes acts; and

- the banning of popular political parties such as Future Forward and the suspension of politicians such as Thanathorn (leader of Future Forward), Pita, and others on technicalities.

As Canada increases its engagement with Thailand, both bilaterally and through ASEAN, as per its Indo-Pacific Strategy, it should not refrain from commenting on Thailand’s lacklustre performance in political rights and democracy. Rather, it should inform the Thai government that, due to the lack of reform since the return to civilian rule, Canada will be unable to support Thailand this coming October in the latter’s bid for a 2025-2027 UN Human Rights Council Seat. Furthermore, in line with Canada’s expressed international commitment to protecting civil and political rights online through the Ottawa Agenda, reactivating negotiations for a bilateral free-trade agreement, which stalled following Thailand’s 2014 coup, should be contingent upon Thailand removing junta-era legislation criminalizing online expression and enabling digital surveillance and repression.

Finally, since 2005, the winning party of each of Thailand’s elections has been overthrown in a military coup, ousted through a judicial intervention, or prohibited from taking power due to military-appointed legislators. Furthermore, hundreds of thousands of Thais have taken to the streets to demand political change. In short, Thailand’s political system does not reflect the popular will. Canada should thus not consider the current government of Thailand to be the sole voice of the Thai people. Rather, Canada should insist that its proposed initiatives in Thailand – bilateral trade agreements, cleantech and clean energy investment, and climate-resilient infrastructure development – be discussed and reviewed by all-party committees and representatives from a variety of civil society organizations.

Thailand’s continued instability also means that Canada’s economic and strategic engagements should remain modest for the time being. The underlying conditions that have given rise to Thailand’s political struggles of the last 20 years have not disappeared. Despite efforts by the Thai military and military-backed governments between 2014 and 2023 to eliminate Thaksin’s influence and reduce the strength and popularity of his electoral vehicles and affiliated mass movements, Pheu Thai remains reliably popular in the country’s north and northeast.

Meanwhile, the youth-led 2020-2021 protests and the success of the Move Forward Party in the 2023 election indicate that there is a large segment of the Thai populace that is seeking a significant break with the past. Moves against either of these parties by establishment forces, including the removal of the prime minister, the jailing of leaders, or the banning of parties could provoke a return to the lengthy and mass-based demonstrations and occupations that have occurred on numerous occasions since 2006.

While Canada should therefore continue with its plans to work with Thailand on cleantech and clean energy, climate-resilient infrastructure, and bilateral trade negotiations, it should develop these partnerships cautiously and with an eye to a more significant partnership in the future.

Taking a broader, longer-term view of the Thailand-Canada relationship

Compared to some of its allies such as the United States, Australia, and Japan – all of which have more significant economic and security engagements with Thailand – Canada is building its relationship from the ground up. Historically, Canada’s engagement with Thailand has primarily revolved around development assistance, including through the current Canada Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI), which has supported numerous local climate action and good governance projects since 2003. However, Canada’s relatively meagre present-day relationship with Thailand should not be considered a disadvantage. While the United States, Australia, and Japan have been placed in awkward situations as a result of their ties to the traditional Thai political establishment, Canada is entering the fray at a time when that establishment is being significantly challenged.

As a result, Canada should take a long-term view of its relationship with Thailand; when the country progresses in its current political transformation, it could be a significant non-traditional partner for Canada. Economically, many of the reforms necessary for Thailand to escape its current middle-income trap, including demonopolizing and the modernization of the education system, are policies proposed by the country’s pro-democracy forces. A continuation of Thailand’s political transformation could also result in the country adopting a much more liberal internationalist foreign policy, providing Canada with a natural ally within ASEAN. In fact, during the period of domestic democratic stability in the 1990s, Thailand was able to play a significant leadership role within ASEAN and in international affairs more broadly. While the military and military-backed governments between 2014 and 2023 were insular and turned towards China economically (and the current coalition government engages in hedging), progressive forces have expressed their willingness for Thailand to commit to multilateralism, democracy promotion, and human rights. Most notably, the Move Forward Party has already begun working more closely with Myanmar’s anti-junta government in exile, the National Unity Government.

In the meantime, to lay the groundwork for deepening the relationship, Canada should increase its efforts to strengthen people-to-people ties with Thailand, encouraging a greater exchange of people and ideas. Currently, the Thai presence in Canada is relatively limited, with a much smaller diaspora than is the case with many other Southeast Asian nations. As Thailand looks to build its soft power and promote its cultural outputs, including with its burgeoning film industry, Canada remains an under-the-radar yet attractive destination for Thai filmmakers to hone their craft and showcase their work. Given the large role that tourism plays in the Thai economy, and both countries’ commitments to sustainability, Canada and Thailand would also have much to gain from exchanging best practices on sustainable tourism.

Finally, strong democracies depend not just on democratic commitments from their governments but also on robust civil societies that deepen citizens’ participation in addressing the issues that impact their communities and that hold governments accountable. This includes long-established democracies such as Canada that are currently facing democratic decline. Canada and Thailand should thus do more to encourage co-operation and capacity-building between their respective civil societies to construct a true people-to-people partnership that goes beyond market actors and the state.

In terms of Canadian engagement with Thai civil society, Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC) should strongly consider supporting a Thailand-focused version of the UBC Myanmar Initiative. With funding from the IDRC, the initiative has been successful in training and supporting Myanmar-based and Myanmar-focused researchers and practitioners in both civil society and academia. This would be an opportunity for the future leaders of “new Thailand,” emerging from the current generation of activists, to learn the art of governance, research and craft solutions to the problems Thailand faces, and share their democratic energy and creativity with Canada.