La version française est à venir.

In September 2023, the Canada-India relationship hit one of its lowest points ever after Prime Minister Justin Trudeau linked the June 2023 murder of a Canadian Sikh activist in Surrey, British Columbia, to agents of the Indian state. But pre-existing strains in the relationship can be traced back to a terrorist attack almost four decades ago, an incident considered the “worst mass murder" in Canadian history.

On June 23, 1985, a bomb exploded aboard Air India Flight 182 to New Delhi, a passenger flight from Toronto bound for London, U.K., over the Atlantic Ocean. The explosion killed all 329 people onboard. The victims included 268 Canadian nationals, most of them of Indian origin, and 82 children under the age of 13. A second suitcase bomb, meant to blow up another Air India flight to Bangkok over the Pacific Ocean, killed two baggage handlers at Tokyo’s Narita airport about an hour earlier.

Despite the scale of the attack, the investigation in Canada, widely reported as “bungled,” led to only one conviction. What’s more, the tragedy remains largely shrouded from Canadian public memory; in a June 2023 Angus Reid poll, nine out of 10 Canadians said they knew little to nothing about the country’s most lethal terrorist attack, which also happened to be the world’s deadliest aviation-related terrorist incident prior to 9/11.

Another frequently overlooked dimension of the tragedy is how it became an enduring source of mistrust in Canada’s relations with India. The factors that contributed to this mistrust include Canada’s failure to prevent the attack; its seeming unwillingness to accept, despite the plot being hatched on Canadian soil and most victims being Canadian nationals, that the tragedy was ‘Canadian’ rather than foreign; a perceived lack of ‘official empathy’ for the victims’ families; and the lasting perception, especially in New Delhi, that Canada takes a permissive attitude toward extremist activities that India believes threaten its territorial integrity.

How were the bombings connected to Canada and India?

Most victims of the Air India tragedy were Canadians of Indian origin. The bombings — believed to be a response to the Indian army storming Sikhism’s holiest shrine, the Golden Temple, in the Indian state of Punjab in 1984 to remove Khalistani militants sheltering inside — were also tied to a British Columbia-based “extremist” group, Babbar Khalsa. The group’s primary demand was an independent Sikh homeland called ‘Khalistan,’ to be carved out of Punjab.

The demand for Khalistan, which New Delhi did and still does consider to be an existential threat, prompted a full-blown insurgency in Punjab in the 1980s and 1990s. The Golden Temple operation, ‘Operation Blue Star,’ which marked a peak of that insurgency, led to then-Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi being gunned down by her two Sikh bodyguards in 1984, and a retaliatory massacre of thousands of Sikhs in northern India. This led many Sikhs to seek refuge in Canada and other Western nations.

The demand for Khalistan among sections of the Sikh diaspora in Canada and alleged intimidation (and now allegations of murder) of Sikh dissidents by New Delhi remain irritants in Canada-India relations. While ties between the two countries have been particularly fraught since the deadly incident in 1985 – which according to many observers escaped both justice and accountability – this was not the first significant challenge in bilateral relations, which has seen many ebbs and flows in the last 70 years.

What were the “cascading series of errors” that failed to prevent the bombings?

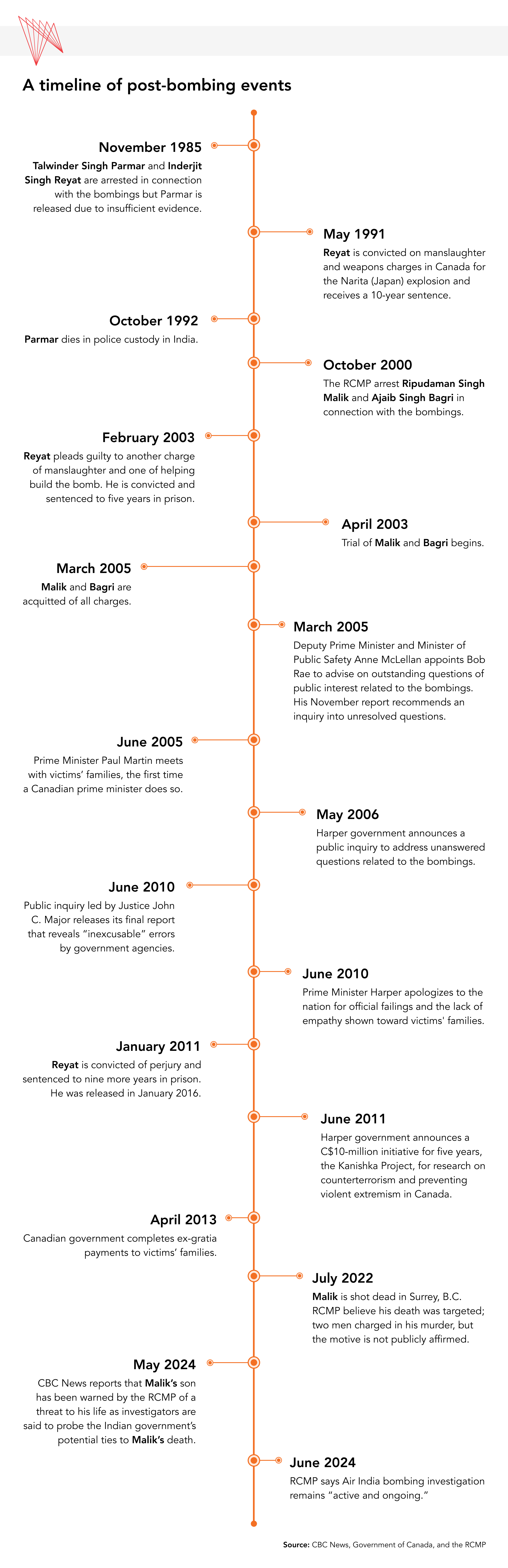

A public inquiry into the bombings by retired Supreme Court of Canada Justice John C. Major, instituted by Prime Minister Stephen Harper in 2006, revealed a series of lapses by Canadian agencies in preventing the Air India bombings. Major’s 2010 report indicated that Canada’s security and intelligence agencies failed to heed warnings about an attack detected months in advance. The report also blamed “turf wars” between the Canadian Security Intelligence Agency (CSIS) and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), and “a cascading series of errors” by government agencies for failing to prevent the attack.

One such error occurred in the days leading up to the bombings. CSIS operatives tailing Talwinder Singh Parmar, founder and leader of Babbar Khalsa, heard what was later understood to be an explosives test conducted by Parmar in a wooded area of Vancouver Island. Canadian agencies reportedly overlooked the incident, with CSIS agents mistaking the sound as a “gunshot.” The surveillance operation was called off on the day of the bombing as security agencies diverted their attention toward a Cold War target, according to the 2010 report, despite the “remarkable and unambiguously alarming behaviour” noted by the CSIS surveillance team.

Furthermore, James Bartleman, then-director general of the intelligence analysis and security bureau at Canada’s Department of External Affairs, testified before the inquiry commission that he had come across a highly classified document from the Communications Security Establishment (CSE) a few days before the bombings, which revealed the threat to Flight 182 from Sikh extremists. But Bartleman said he received a “hostile reception” upon apprising the RCMP of this threat. Although his testimony was discredited by government counsel and the CSE at the hearings, the inquiry found Bartleman’s testimony credible and corroborated by other pieces of evidence. The inquiry report concluded that a “great deal of effort was expended by [Canadian] government agencies” at the hearings to prove that information from various sources about the imminent attack “lacked particularity and specificity.”

Another set of errors on the day of the bombings and the day before, as detailed in the inquiry report, include:

- On June 22, 1985, a man identifying himself as ‘Manjit Singh’ checked in for a Canadian Pacific flight from Vancouver to Toronto, which connected to Air India Flight 182. Despite not having a confirmed ticket for the onward flight, the request to transfer his bag, which contained the bomb, to Air India Flight 182 was granted by the Canadian Pacific Air Lines agent.

- Although Manjit Singh did not board the flight in Vancouver, his “unauthorized” bag was still transferred.

- According to the 2010 public inquiry report, on the day of the bombings, Air India’s X-ray machine malfunctioned in Toronto after scanning 50-75 per cent of the checked-in bags. Hand-held sniffers, which had been proven ineffective during tests conducted in January 1985 in the presence of officials from the RCMP and Transport Canada, were then used to screen the bags. The report also states that security personnel were not adequately trained to detect an adverse signal from the ‘sniffers.’

Who has been held accountable for the killings?

According to John C. Major, "error, incompetence, and inattention" by Canadian agencies pervaded all stages of this episode: before the bombings, in their aftermath, and during the subsequent investigation and legal proceedings.

The only conviction was that of Inderjit Singh Reyat, a Duncan, B.C.-based auto electrician. Reyat received a 10-year sentence in 1991 for two counts of manslaughter and four explosives charges related to the explosion at the Narita airport in Tokyo. In 2003, he pleaded guilty to another charge of manslaughter and one charge of helping to build the bomb. He was handed another five-year sentence and remains the only person convicted in relation to the bombings.

Talwinder Singh Parmar, the founder of Babbar Khalsa and considered the mastermind of the Air India attack in the 2010 report, was also arrested in November 1985 on weapons, explosives, and conspiracy charges related to the bombings. Charges against him, however, were dropped soon after his arrest due to insufficient evidence.

Ottawa refused New Delhi’s request to extradite Parmar, but he was reportedly killed in 1992 in police custody in India after travelling to that country. Parmar remains a symbol of Khalistani activism in Canada, even today. For instance, his portrait identifying him as a ‘martyr’ has appeared on a billboard next to the Khalistan flag outside the Guru Nanak Gurdwara in Surrey, B.C., the same gurdwara where Sikh activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar was gunned down in June 2023.

In 2000, Vancouver-based businessman Ripudaman Singh Malik and Ajaib Singh Bagri, a millworker from Kamloops, B.C., were arrested for conspiracy and mass murder in connection with the 1985 bombings. The arrests, 15 years after the murders, resulted in one of the most expensive trials in Canadian history. It concluded in 2005 with both men found not guilty and calls from victims’ families for a public inquiry to address unanswered questions. Serious lapses in the prosecution’s case and concerns about the credibility of key witnesses were pointed out by the presiding judge, who remarked that CSIS’s destruction of 150 hours of taped telephone calls was a case of “unacceptable negligence.” According to RCMP documents, CSIS wanted the tapes destroyed to protect the confidentiality of one of their agents who had infiltrated the extremist group that was allegedly behind the attack.

Why is Canada accused of “indifference”?

The lack of accountability in Canada’s worst terrorist incident, coupled with a belief by some that the tragedy could have been prevented, has engendered a perception in India, and in some quarters in Canada, that Ottawa has allowed extremism to fester on Canadian soil. Additionally, perceptions linger in Canada that the tragedy was “foreign,” as the motive for the bombings was tied to “alleged grievances rooted in India.” Finally, the “absence of remembering” in Canadian public memory raises questions about systemic racism. Most of the victims, including the Canadian nationals, were of South Asian origin.

While the public inquiry stopped short of describing the Canadian response toward victims’ families and investigation of the bombings as ‘racism,’ it called out the government for its “callous attitude” toward the victims’ families. One noted example of this ‘callousness’ is that Canadian officials were not present at Heathrow Airport in London, U.K., to aid victims’ families when they arrived there after the bombing. The first memorials in Canada to commemorate the victims were erected more than two decades later, in 2007.

In 2010, 25 years after the bombings, Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized for Canada’s official failings, including the treatment of victims’ families and the “administrative disdain” that failed to meet the “legitimate need for answers.” He also acknowledged that “this was not an act of foreign violence,” but was conceived and executed in Canada “by Canadian citizens,” and that the “victims were themselves mostly citizens of Canada.” Harper’s apology, which came after the public inquiry report was released, however, has not erased concerns about Canada’s “indifference” and neglect in handling this case.

Why does the tragedy remain a festering sore in Canada-India relations?

Canada’s seeming “indifference” to preventing and punishing the Air India bombings still negatively impacts its relations with India, a country that has recently accused Canada of permitting extremist Khalistani activities that threaten India’s territorial integrity to happen on its soil. Such rhetoric sharpened on the Indian side after Trudeau’s September 2023 statement before the House of Commons that the Canadian government had “credible” intelligence linking the murder of Canadian Sikh activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar to agents of the Indian state. New Delhi immediately rejected the allegations as “absurd” and in turn accused Canada of being a “safe haven” for terrorists and “anti-India activities.”

In June 2023, Trudeau’s then-national security adviser, Jody Thomas, stated that India was among the top actors for foreign interference in Canada. Since then, India has been accused of foreign interference and transnational repression not only in Canada but also in the U.S. and Australia. The allegations in Canada include meddling in electoral processes, intimidation of dissidents among diasporic groups, and assassinating a Canadian citizen on Canadian soil. The assassination allegation also found credence in an indictment in a New York court that was unsealed in November 2023 on a ‘murder for hire’ charge in the U.S. involving an Indian official who reportedly targeted a pro-Khalistani Sikh activist.

Despite the similarities in the Canadian and U.S. allegations, there is a discernable difference in India’s attitude toward the two cases. It appears to be ‘business as usual’ with Washington, and New Delhi has promised an internal investigation. Media reports suggest the investigation blames ‘rogue operatives,’ implying that the murder plot was not officially sanctioned. However, India doubled down on its position vis-à-vis the Canadian case, saying that Canada “has given space to extremists and terrorists” in its politics.

Ottawa’s perceived indifference, whether in the past or now, may be an issue of serious concern, but it neither justifies alleged extra-territorial assassinations nor the repression of overseas dissidents by a foreign power.

Whether the Indian government’s claims of Canada’s laxity regarding extremism are convincing or not, the Air India bombings case remains a very uncomfortable and largely unaddressed issue in the bilateral relationship. Canada’s relatively weaker geopolitical significance may partly explain the differing attitudes New Delhi has displayed toward Washington and Ottawa, but the long-standing seed of distrust planted by the Air India tragedy cannot be overlooked. Canada has remained an “outlier” among Western nations that have, over the past decades, forged closer strategic ties with India amid rising geopolitical rivalries.

This distrust has occasionally surfaced and fractured the relationship even prior to Prime Minister Trudeau’s statement in September 2023. For instance, in June 2023, about two weeks before Nijjar’s murder, Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar lashed out at Canada for the apparent glorification of the assassination of Indira Gandhi during a Sikh parade held in Brampton, Ontario. A float in the parade depicted Gandhi’s killing at the hands of her two Sikh bodyguards.

In 2018, during Trudeau’s visit to India, Jaspal Atwal, a B.C. man who was an alleged member of a banned terrorist group, the International Sikh Youth Association, and had been convicted of attempting to murder an Indian cabinet minister while the latter was in Canada in 1986, was invited to attend two events alongside the Canadian prime minister, an incident that would subsequently embarrass Ottawa.

The road ahead

There appears to be significant dissonance currently in how Canada and India perceive threats emanating from pro-Khalistani activism. New Delhi resents Western governments ignoring what it regards as the resurgence of a serious security threat. While the Canadian government has always maintained that it respects India’s territorial integrity, Canadian law protects calls for secession as ‘free speech,’ provided those calls do not cross the threshold into criminal activity. The Indian government’s definition of terrorism and extremism also differs from how these issues are defined in the Canadian legal system. However, serious questions are being raised in recent media reports about the nature of Khalistani activism that allegedly occurs on Canadian soil.

Bilateral relations remain besieged by an ongoing criminal investigation in Canada into the potential involvement of the Indian state in the murder of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, who New Delhi designated as a ‘terrorist’ in 2020.

In May 2024, the RCMP arrested and charged four Indian nationals, apparently associated with a criminal group from Punjab called the Lawrence Bishnoi Gang, for the murder. India’s external affairs minister, S. Jaishankar, responded to the arrests by saying that Canada has allowed ‘criminals’ to enter the country.

An unfortunate legacy of the Air India bombings is that a tragedy that should have united two nations in grief over the loss of more than 300 lives has instead prompted decades of mistrust and misgivings. If historical roadblocks are not confronted and addressed, the road ahead for Canada-India relations may become even bumpier than it is now.

• Edited by: Vina Nadjibulla, Vice-President Research & Strategy, Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada; Erin Williams, Senior Program Manager, Asia Competencies, APF Canada; and Ted Fraser, Senior Editor, APF Canada.